Ferry Field, 1906-1926

By 1902 it was apparent that the Regents Field facilities were no longer adequate, either to handle the crowds thronging to Michigan football games or for the general recreational needs of the student body. The old playground area on campus and the many vacant lots around town that had been traditional sites for student baseball and football games were increasingly taken over by university buildings, and private housing. The Alumnus Magazine commented in 1902, "now the campus is so full of buildings that for a number of years the batting of balls has been wholly forbidden because of the danger to windows and apparatus. With the new medical building and the new engineering building there will scarcely be room enough for a football team to practice."

Dexter M.

Ferry

Among those concerned about the

university's athletic facilities was Detroit businessman and

philanthropist Dexter M. Ferry, head of the Ferry Seed Company. For a

number of years Ferry had supported a fellowship in botany at the

university. In 1902 he again demonstrated his generosity by purchasing

and donating to the university twenty acres of land just north of Regents

Field to be used for athletic purposes. The Board of Regents gratefully

accepted the donation and ordered that Regents Field and the new property

would be known as Ferry Field. Several small purchases by the Athletic

Association extended the parcel westward to the railroad tracks, bringing

the entire Ferry Field complex to 38 acres.

Ferry also provided funds for construction of a brick wall extending around three sides of the property. An ornamental gate at the northeast corner of the field included ten ticket windows. The gateway, designed by Albert Kahn Architects of Detroit and constructed of Bedford stone, red paving brick and wrought iron gates, was completed in 1906 at a cost of over $10,000. All together the value of Ferry's contributions was estimated to be in excess of $30,000.

Bricklayers at newly completed Ferry Field

gate.

Work on improving the new field began immediately. Much of the parcel was low, wet land. Drainage tile was laid and, with the assistance of the Ann Arbor Railroad, more than ten thousand yards of sand and gravel were hauled on site to fill low spots. Six inches of fine topsoil was laid down to insure a heavy turf.

Lorenzo "Tommy" Thomas, groundskeeper for the Athletic Association, at work on the Ferry Field grounds, ca. 1907, about where the baseball field is now. Thomas would later install the turf at Michigan Stadium. The State St. wall and the groundkeeper's house are in the background.

The Board in Control of Athletics began planning for a new stadium by the investigating the latest designs at the major eastern schools.

The new stadium was ready for the opening of the 1906 season. The north bleachers, on the site of what is now the Intramural Sports Building, seated over 9,000 fans and included a covered press box along the top row. Some of the Regents Field bleachers were moved to the south sideline to accommodate another 6,000 spectators. Temporary stands erected in the west end zones brought total capacity to about 18,000. It was estimated that the stadium eventually could be expanded to hold 30,000 fans.

Michigan inaugurated the new gridiron with a 28-0 win over Case on October 6, 1906. Fullback John Garrells was the star of the game, scoring the new field's first touchdown on a short run and keeping Case pinned down with his great punting. Following the 1906 season Michigan withdrew from the Western Conference in a dispute over new conference rules. For the next eleven years Western Conference teams were barred from scheduling Michigan (Minnesota violated the ban in 1909 and 1910). As a result, Michigan looked east for its major competition and the "big games" at Ferry Field featured Pennsylvania, Cornell, and Syracuse. The 1916 homecoming game against Penn attracted 25,584 fans.

1907 Pennsylvania game, UM lost 6-0 before 19,500 homecoming fans.

A "club house," or locker room, located at the east end of Ferry Field, was completed in time for the 1912 football season. Previously the Michigan and visiting teams used the locker rooms in Waterman Gym on the north edge of campus, making the almost one mile trek along State Street before and after games. The building, designed in the style of an old English club house by the Detroit architectural firm of Smith, Hinchman and Grylls, provided separate locker room facilities for home and visiting teams as well as offices and lecture rooms for the Michigan coaches, as well as a lounge area. Total cost of the club house and equipment was $37,000. Now known as the Marie Hartwig Building, the former club house currently houses the Ticket Office, Sports Information Office, Development Office and other Athletic Department administrative offices.

The first significant expansion of Ferry Field came in 1914 when the old wooden bleachers along the south sideline, that had once stood on Regents Field, were replaced with concrete bleachers. Comprised of 55 rows and seating 13,000, the new bleachers were of a unique design that was supposed to ensure that everyone of average height would have at least four inches clearance above any person sitting in front of him. This was achieved by constructing the first eleven rows on 9-inch risers, the second eleven on 10-inch risers, the third on 11-inch risers, the fourth with 12-inch risers and the last eleven with 13-inch risers. The Alumus Magazine reported, "This arrangement, which gives the stand a graceful, concave appearance, has, according to the athletic authorities, caused a rather amusing rumor to be circulated to the effect that the stand was sinking in the middle." The new bleachers raised Ferry Field seating to 21,000, though up to 25,000 were squeezed in for a few games.

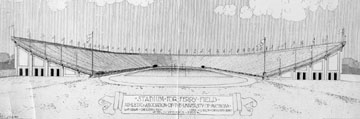

At its January 1914 meeting, the Board of Regents had authorized the Board in Control of Athletics "to make contracts for the new cement bleachers at Ferry Field, in accord with the contemplated design, provided that no financial responsibility shall attach to the Board of Regents through these contracts." The "contemplated design," was prepared for the Board in Control by engineer Hal Weeks (eng. 1903-06, member of the 1907 football team) It called for the transformation, over a seven year period, of Ferry Field into a horseshoe style, concrete stadium with a seating capacity of at least 45,000. The south bleachers were the only part of the grand design to be completed. Cost factors, the interruption of World War I and Fielding Yost's vision for an even larger stadium led to a piecemeal expansion of Ferry Field instead.

Proposed Expansion of Ferry Field, 1914

The surge of popular interest in football in the years following World War I, as well as Michigan's return to competition in the Western Conference, created unprecedented demand for tickets. Average attendance at the big games in 1919 and 1920 was over 23,000. With the profits the two seasons generated, the Board in Control returned to the question of expanding Ferry Field. James Cissel, professor of structural engineering in the College of Engineering, was appointed to conduct a study of the feasibility of completing the U-shaped stadium. He concluded that remodeling Ferry Field as planned would not suffice and recommended a new stadium on a new site. Lewis M. Gram, professor of civil engineering and member of the Board in Control, was also urging Yost to recognize the error of building at Ferry Field. "If we build the north stands like the south" Gram wrote, "we will have only 42,000 seats. This will be inadequate 10 years from now." He suggested expanded bleachers to meet the current crisis and construction of a new stadium on the model of the Yale Bowl or the University of Washington Stadium.

Somewhat surprisingly, Yost responded with an initial skepticism. Citing problems created by traffic at the Yale, Princeton and Harvard stadiums, he wondered how crowds of over 50,000 could be handled in Ann Arbor. Besides, he asked, "where could we get the money to pay for a new stadium?"

The Board in Control elected to follow the advice of the engineers. Wooden bleachers at the west end of the stadium were enlarged in 1921, connecting to the north and south bleachers and fully enclosing the west end of the field. With the temporary bleachers at the east endzone, Ferry Fields capacity reached 42,000. A decision on a new stadium was put off until a later date.

Ferry Field, 1922 Illinois game, attendance 41,000.

Ferry bleachers covered with plywood

for protection during off-season

An estimated 50,000 fans jammed the enlarged Ferry Field for the 1923 Ohio State game. The east end bleachers were expanded in 1924 in anticipation of a

sell-out crowd for the Wisconsin game, and again in 1926, bringing Ferry Field's official capacity to 46,000.

More than 48,000 packed the stands for games against Minnesota, Illinois and Wisconsin in 1926 to watch the exploits of Michigan's All-American "Benny to Bennie" combination (quarterback Benny Friedman and end Bennie Oosterbaan.)

Ferry Field, 1924 Wisconsin game, attendance 46,000.

If Yost's initial skepticism was genuine, he soon overcame any doubt about the need for a new stadium. As early as 1923, he began conceiving plans for a new and bigger stadium. One of the first to get a peek at Yost's vision was C. Joe Galloway, a 1925 graduate of the College of Engineering. In a letter to the Michigan Alumnus Galloway recalled:

While at summer camp, Camp Davis on Douglas Lake in 1924, Prof. Harry Bouchard told me that there would be a vacancy in geodesy & surveying for a student assistant and he would like to recommend me for the job. Since I was working my way, I told him if accepted I would be most grateful. He did and I was appointed.

One day Prof. C.T. Johnson (head of the department) and Coach Yost came into the instrument room. Coach requested someone go with him to help determine if drainage could be made possible of a rather large sunken area not far from Ferry Field. I was selected and I drove to an old glaciated depression. Upon arriving and, having brought with me a transit and stadia board, we began taking elevation shots. Coach Yost was my rodman. Yost wanted to know if there was enough fall from the bottom of the depression to permit drainage to the storm sewer. Several shots were made, and after computing, I found there was sufficient gradient to drain the sunken area. We discussed the feasibility of making this natural bowl into a stadium. Coach Yost said, "Galloway, one day this will be the new Michigan Stadium."

We returned to the campus, parking the car in the parking area behind the Lit Building and we talked for a while about this dream of his. He thanked me for going with him for which I told him "That's fine, glad to have been the one chosen."

Two or more models to scale were made and one was made by my fellow men in the department.

Coach Yost's dream became a reality - the new Michigan Stadium was built and Ferry Field had served its time as Michigan's gridiron."

Ferry Field had been a comfortable home for the Wolverines. Over 21 seasons, all but one under the coaching of Fielding Yost, Michigan compiled a home field record of 90 wins, 13 losses and 2 ties.

Following the 1926 season, the old stadium began to come down. The end zone bleachers were razed and the north bleachers made way for the new Intramural Sports Building, the first structure of its kind designed expressly for intramural sports. The playing field was now devoted exclusively to track and field, except for use as a military training ground during World War II and as the site of many graduation ceremonies.

Ferry Field hosted the Midwest trials for the 1924 U.S. Olympic team and two of Michigan's own went on to win Olympic medals; William DeHart Hubbard took the gold medal in the broad jump and James Brooker won bronze in the pole vault. Ferry Field has been the site of many great individual performances in Big Ten track championships, none more remarkable than Jesse Owens' efforts in 1935. Within a period of two hours, the Ohio State sophomore set world records in the 220 yard dash - :20.2, the broad jump - 26 ft. 8 1/4 in., the 220 yard low hurdles - :22.6 and tied the world record in the 100 yard dash - :09.4 seconds. A plaque at the southeast corner of Ferry Field commemorates Owens' incomparable performance.

Jesse Owens setting world record in broad jump, 1935.

Image Credits:

- Dexter M. Ferry - Dexter M. Ferry Papers, Box 17

- Ferry Field Gates - BHL, Ath. Dept., Box 12, Ferry Field

- Lorenzo Thomas at Ferry Field - BHL, Alumni Assoc., Box 135, Ferry Field

- 1907 Penn game kickoff - BHL, Ath. Dept. Box 3 out.

- Ferry Field Expansion Plan - BHL, Ath. Dept. Box 12, Ferry Field

- Ferry Field, 1921 - BHL, Alumni Assoc., Box 135, Central campus aerials.

- Ferry Field, 1922 Ilinois game - BHL, Ath. Dept., Box 12 Ferry Field

- Ferry Field, 1924 Wisconsin game - Michganensian, vol. 27, 1923

- Jesse Owens, long jump - BHL, Ath. Dept., Box 41, 1935-1937

top | previous | next

| Stadium Home Page | Ath. Dept. MGOBLUE |

Ath. History | Bentley Library