Snapshots of U-M History

A Most Hopeful Experiment

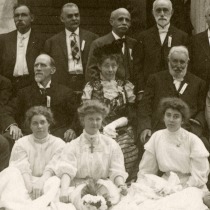

Pioneer Madelon Stockwell was the first woman to attend U-M, changing the campus forever.

By Rachel Reed

To help celebrate U-M’s Bicentennial, the Bentley continues its series of stories about “firsts” in Michigan’s history, including the first time U-M opened its doors to women.

It’s the winter of 1870, and a soft snow blankets the University of Michigan’s rural campus. Students hurry to class, shivering against the bitter February winds. Among them, a face like anyother, yet perceptibly different. This one, clad in a modest bonnet, was a woman. Her name was Madelon Stockwell.

Although women had been asking for admission to the University of Michigan since the 1850s, Stockwell was the first to be accepted, in a controversial move that one school administrator called a “dangerous experiment.” Higher education for women, and indeed education at all, was still hotly debated. Could women learn on the same level as men? Would it hurt their bodies, or their chances for marriage? Was it even decent?

Although women had been asking for admission to the University of Michigan since the 1850s, Stockwell was the first to be accepted, in a controversial move that one school administrator called a “dangerous experiment.” Higher education for women, and indeed education at all, was still hotly debated. Could women learn on the same level as men? Would it hurt their bodies, or their chances for marriage? Was it even decent?

Stockwell, who had already graduated from Albion College in 1862, came to Michigan to pursue a master’s in Greek studies. She bore the stares and occasional unkind remarks with a characteristic imperviousness, even when their jokes seemed tinged with venom. During a Greek class, for example, she was asked to read aloud a passage from Sophocles’ Antigone, in which one sister says to another, “… we are by nature women, so not able to contend with men; and in the next place, since we are governed by those stronger than we, it behooves us to admit to these things and those still more grievous.” Still, Stockwell opened the door for future Michigan women to follow, with 33 more enrolling the following September.

Some of these early female students later reported being derisively called “mister,” or being outright ignored in classes. Others found it difficult to rent boarding rooms, because townspeople didn’t understand or approve of them. The University, to its credit, made no special rules for the new female cohort. It did not institute in loco parentis-style supervision as was the norm at most women’s colleges, and women theoretically enjoyed the same privileges as their male counterparts.

Women may have enjoyed the same theoretical freedoms as men, but not the same facilities. In 1891, Detroit real estate mogul Joshua Waterman donated $20,000 to the school to construct a much-needed gymnasium. Although Waterman himself had intended the gym for use by both men and women, it became clear that many male students were unwilling to share—and so female students went to work to raise funds for own. This newly formed League of women begged the Michigan legislature, and then women from all over the state, for money to complete their annex to the gymnasium. By the end of 1895, they had completed their mission, and work began on a space of their own, which became the social hub for women on campus for decades.

Women may have enjoyed the same theoretical freedoms as men, but not the same facilities. In 1891, Detroit real estate mogul Joshua Waterman donated $20,000 to the school to construct a much-needed gymnasium. Although Waterman himself had intended the gym for use by both men and women, it became clear that many male students were unwilling to share—and so female students went to work to raise funds for own. This newly formed League of women begged the Michigan legislature, and then women from all over the state, for money to complete their annex to the gymnasium. By the end of 1895, they had completed their mission, and work began on a space of their own, which became the social hub for women on campus for decades.

Things weren’t all bad for female pioneers at the University, however. By the time Michigan’s first female graduates earned their degrees in 1871, women had at least found a fierce advocate in James Burrill Angell, U-M president and ardent defender of coeducation.

Said Angell, in one of many speeches supporting Michigan’s admittance policy, “If we are still to regard [women at Michigan] as an experiment, it must certainly be deemed a most hopeful experiment.”

Today, Stockwell’s legacy echoes on in the halls of her namesake dormitory, and in Michigan’s student body, nearly half of whom are women.