Snapshots of U-M History

The Great Society and Michigan

On the 42nd anniversary of Lyndon Johnson’s death, the Bentley takes a look back at how months of persistence and planning came to unveil the president’s monumental, generation-defining speech at the University of Michigan—and how the Bentley received a treasure after it was all over.

by Brian A. Williams

Exactly six months to the day after the assassination of John F. Kennedy, President Lyndon B. Johnson gave the commencement address to the University of Michigan graduating class of 1964.

The invitation to be the commencement speaker had originally been extended to Kennedy, with the hope that he would return to the place where he made the first public proclamation of the idea of the Peace Corps on October 14, 1960. U-M President Harlan Hatcher wrote to Kennedy on October 11, 1963, inviting him to give the address at the University’s 120th commencement scheduled for Saturday, May 23. Hatcher’s letter elicited a perfunctory response from Kenneth O’Donnell, special assistant to Kennedy. O’Donnell’s reply conveyed thanks for the invitation, but indicated that it was impossible for the President to make a commitment “even on a tentative basis, since he has no way of knowing what the official demands on him will be next May.”

The events in Dallas on November 22, 1963, sent the nation into mourning while abruptly thrusting Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson into the presidency. On December 19, 1963, Hatcher renewed the invitation to speak at commencement to the new Chief Executive. The invitation touted an audience of some 6,000 graduates and representatives from 97 nations. Once again, O’Donnell cited the heavy demands on the President’s schedule and suggested that U-M go ahead with plans “not counting on” the President’s appearance. But he left the door slightly open, suggesting that U-M check back again in April for a definitive answer.

Preparing for a President

The University’s perseverance was rewarded on April 14, 1964, when President Johnson placed a call to Hatcher to accept the invitation on the condition that commencement could be moved up a day to Friday, May 22, to accommodate the President’s schedule.

The University agreed and set about the monumental task of changing plans, mobilizing personnel, and organizing logistics for the Presidential visit, including shortening the commencement ceremony. Recent commencement ceremonies in Michigan Stadium had been averaging over two and a half hours. A streamlined ceremony was planned along with a precisely-timed agenda.

Myriad smaller details also needed to be nailed down. The University was furnishing the academic gown for Johnson, and received the President’s measurements from his personal secretary: height: 6’ 3-1/2”, chest: 41”, and hat size: 7 3/8”. There were also more sobering possibilities to plan for. From the time the President landed in Detroit until he was airborne and on his way back to Washington, one operating room at the University Hospital was kept cleared and ready while U-M’s top cardiologist and teams of neurosurgeons and thoracic surgeons were kept on standby alert. A lecture hall in the hospital was reserved for use as an emergency press conference room. An ambulance staffed by three doctors and nurses was also on standby at the stadium, and the route to the hospital had been planned and tested.

Abundance and Liberty for All

It was a warm day as the graduates made their way to their seats in the middle of the football field where the temperature was close to 90 degrees. People filled the stands for what would be the best-attended commencement in the University’s history. Estimated attendance ranged from 70,000 to more than 86,000 people. It was also the first U-M commencement to be televised.

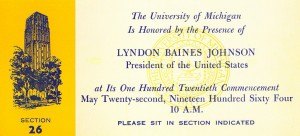

A ticket for the May 22, 1964 commencement, which had changed dates and had been severely modified to accommodate its featured speaker.

President Johnson landed at Metro Airport at 9:00 a.m. and was greeted by a delegation that included U-M Executive Vice President Marvin Niehuss, and a commission of political leaders including Governor George Romney, U. S. Senators Phil Hart and Patrick McNamara, Detroit mayor Jerome Cavanagh, and August Schoole, a labor leader. Several members of Congress from Michigan were also on hand. A fleet of four Marine helicopters bearing the President and his entourage took off from Metro and landed near Michigan Stadium at 9:50 a.m.

At 10:00 a.m., the procession began in the Michigan Stadium tunnel entrance. As the dignitaries entered the stadium, Director Wiliam D. Revelli led the Michigan Band as they played “Hail to the Chief” during the procession across the field to the stage. Due to time constraints, degrees were granted in course. Only the doctoral candidates were mentioned by name during the ceremony.

At 10:55 a.m., the President began his 20-minute speech. “I have come today from the turmoil of your capital to the tranquility of your campus to speak about the future of your country,” Johnson said as he read from a teleprompter. As backup, sitting on the lectern, he had a ring of 3”x5” index cards with the text of the speech.

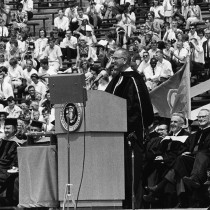

Lyndon Johnson’s commencement address on May 22, 1964, was 20 minutes long, 10 minutes over what he’d been allotted by event planners. (HS1829)

In what would become his administration’s most notable statement on domestic policy, Johnson proceeded to speak of “the Great Society.” In powerful tones, Johnson told the audience that “the Great Society rests on abundance and liberty for all. It demands an end to poverty and racial injustice.”

Outlining “three places where we can begin to build the Great Society,” Johnson focused on rebuilding cities, preserving nature, and enriching classrooms. Johnson pledged to “establish working groups to prepare a series of conferences and meetings—on the cities, on natural beauty, on the quality of education, and on other emerging challenges.” These studies would “begin to set our course toward the Great Society.”

Johnson asked the audience, “Will you join in the battle to give every citizen the full equality which God enjoins and the law requires—whatever his belief, or race, or the color of his skin? Will you join in the battle to give every citizen an escape from the crushing weight of poverty?”

The importance of his speech was quickly recognized. Regent William Cudlip spoke with Johnson immediately after his address. He congratulated the President, and said to him, “You have characterized your administration because ‘the Great Society’ was the theme of your address and you mentioned it several times.” In a sworn affidavit, Cudlip recounted Johnson’s response as, “You are right, that will be the description of my administration’s program next year and it reflects the goals we are trying to achieve.”

For Future Generations

The next day, Johnson sent a telegram to Hatcher noting that he appreciated “the warmth of your hospitality and the extent of your kindness yesterday.” He concluded the telegram by stating, “I am very proud to be an alumnus of your great and enlightened university.”

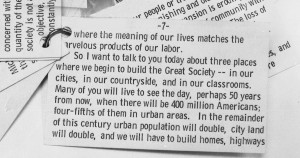

The note cards on the lectern during Johnson’s speech are now housed at the Bentley Historical Library.

Realizing the significance of the speech, archivists from the Michigan Historical Collection (predecessor of the Bentley Historical Library) recommended asking for the original copy of the speech for the archives. On July 20, 1964, a letter and a ring of index cards was sent to U-M. The text of the letter read, “After a great search of inside suit coat pockets, the cards that the President used for his Ann Arbor speech were found. It was a pleasure for him to sign them and have me send them to you.” Those notecards are among the treasures in the archives.

Although it was an arduous task at the time, the tenacity required to secure such an important figure paid off. This great, impactful speech will forever live on in the tomes of the University of Michigan’s history.

Sources Note

Sources used in this article came from the following archival collections in the Bentley Historical Library: U-M. Assistant to the President records (Box 8), UM. Chief Marshall records (Box 5), Harlan Hatcher papers (Box 36). Additional published sources include The Michigan Alumnus, June 1964 (vol. LXX, no. 9) and The Anatomy of a Speech: Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society Address by Robert M. Warner (Ann Arbor, Mich. : Michigan Historical Collections/Bentley Historical Library, 1978).