News Stories

On Top of the World

Annie Smith Peck came to U-M just after women were admitted, and excelled in spite of prejudice against female scholars. Then, she started climbing mountains, and further redefined what most people thought women could do.

by Alex Boscolo

In 1895, Annie Smith Peck climbed the 14,692-foot Matterhorn Mountain on the border of Italy and Switzerland. The morning of her historic ascent, she left base camp at 3:15 a.m. Climbing through the dark, aided by two mountain guides, she thrilled at the excitement of becoming the third woman to achieve the peak. By sunrise, they had reached a second stopping point where the party dropped off some extra gear. Annie appraised the journey ahead—and made the choice to leave her skirt behind. Five hours later, she reached the historic summit of the mountain. She was not quite famous, but thanks to her fashion choices, she was certainly notorious.

At the time of her historic Matterhorn ascent, Annie was 45 years old. She would go on to climb mountains in South America and would earn her living writing books and giving public lectures about archaeology, traveling, and of course mountaineering. Emelia Earhart once said she “felt like an upstart compared to Miss Peck.”

Even before she started climbing, Peck had always been a pioneer. From 1881-1883 she been a professor of Classics at Purdue University and Smith College, and she was the first woman admitted to the American School of Classical Studies, in Athens, Greece. She’d also been part of what U-M President Henry Tappan called a “dangerous experiment”: the admission of women to the University of Michigan.

Higher Education

Four years after the first woman, Madeline Stockwell, enrolled at U-M, Peck came to Ann Arbor in 1874. Annie was 27 years old, and much older than the average first-year student. She had already been teaching high school for several years in Saginaw, and was discouraged by the fact that she was earning far less than her three brothers. She set her sights on higher education as a way of supplementing her income, despite her family’s disapproval.

In January 1874, she wrote a sternly worded letter to her father in which she complained, “Why you should recommend for me a course so different from that which you pursue, or recommend to your boys is what I can see no reason for, except the example of our great grandfathers and times are changing rapidly in that respect. . . I hope you will make yourselves easy about it. I think when we have talked the matter over we shall agree better. I certainly cannot change.”

Annie Peck Smith in 1878. Image BL000021

She earned her bachelor’s degree in 1878, and praised her education in letters to her father, remarking, “I had a chat with Mr. Sellers, a classmate. Speaking of who is the best scholar, he said, ‘Without flattery, I honestly think you are,’ and I said, ‘Nonsense.’ He declared that he had heard ever so many boys say the same thing. The girls here are far from being appendages.” She also noted in her diary how she was enjoying her classes in Greek and Latin. Her academic excellence was registered by several other scholars, including President Angell, whom she claimed called her the best scholar in the class at her graduation. She also said she had in writing an accolade from him that remarked how she “distinguished herself in every class.”

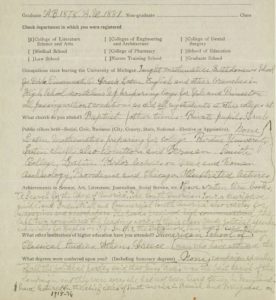

Most of what we know about Peck’s time at the University of Michigan comes from her own writing. In addition to her diaries and letters, she also filled out an Alumnae Survey in 1924. (It can be viewed in person at the Bentley or online.) The survey is covered in pages of tiny, cramped writing detailing her accomplishments. To the completed document, she attached a rave review of one of her three books about mountain climbing, The South American Tour, and a pamphlet about her lectures, in which she regaled audiences around the globe with stories of her exploits.

In filling out the survey, she seems to have largely ignored the questions, opting to leave most of them blank or use the lines provided to continue her description of her accomplishments. For all of the questions on the second page, she gives a one word or one-line answer, and uses the extra space to discuss her career. In response to “In your opinion who are the ten most outstanding women who have ever at any time attended the University of Michigan, considered from the standpoint of human service?,” she wrote “Have no idea” and continued a discussion of her teaching experience. Her answer to “Achievements in Science, Art, Literature, Journalism, Social Service, etc.” discusses her writing in detail and fills up the spaces left for two other questions about post-graduate schooling.

A page from Peck’s detailed answers to the alumae survey archived at the Bentley.

No one can deny Peck valued her education. She wrote extensively of her classes, noting that “I never missed a recitation during the four years,” apparently one of only two students to achieve this feat. She also was “particularly pleased when after the Greek examination. . . Professor Pattengill told me that I was the only one in the class [of more than 60 students] who gave correctly the construction of ten infinitives in one paragraph of Thucydides.” However, when asked to elaborate about the value Michigan added to her life, she wrote that “My character and ideas were well formed before entering the University . . . [there was no value] aside from the naturally broadening influence of a four years’ course of study.” Since Peck was 27 years old when she entered college, she might be excused for saying that her character was well-formed by the time she entered college. However, another influence on her lukewarm response might have been her inability to gain for herself acceptance into the Phi Beta Kappa honor society.

Scholarship and Censure

According to scholar Hannah Scialdone-Kimberley, who wrote her doctoral dissertation on Peck, and later published the biography of Peck titled A Woman’s Place is at the Top (St. Martin’s Press, 2017), Peck “made several inquiries regarding her admittance to Phi Beta Kappa,” including to Harry Burns Hutchins, president of the University of Michigan (1909-1920), and E.M. Carroll, the secretary of the elite academic society. Scialdone-Kimberly argues that Peck “made it clear that her scholarship was just as important as her reputation as a climber.” Her persistence transcended University presidencies. By 1928, she was writing to President C.C. Little, complaining that many of her classmates were recognized “while I apparently had been overlooked.” Apparently Little did not respond favorably, because she was never admitted to the society.

Despite this academic setback, Annie’s achievements were still monumental for her time. She had an advanced degree, was educated in Europe, taught both men and women, wrote several books and traveled the country giving lectures on her climbing, as well as the importance of science and diplomatic relations with other countries. She also became, as she wrote in her survey, the person to have “reached a higher point on this hemisphere than has been attained by any [other] . . . man or woman.”

Her accomplishments, however, were often overshadowed by her gender and dress, much to Annie’s dismay. Scialdone-Kimberly wrote that Peck “argued that much of the [famous] criticism of her dress was an attempt to censure her for working in the male realm.” And on her survey, Annie bitterly noted that, at a time she was up for a job, Professor Pattengill, a man who she deeply respected, told her that “You are undoubtedly better qualified for the position than any young man we shall be likely to get. At the same time there is no chance of your getting it.”

Peck struggled her whole life to be recognized for her achievements. Even so, her legacy opened doors for women to achieve in science and in athletics, and she continued traveling and mountain climbing until her death at the age of 84.