Magazine

Michigan’s Polar Bears

The Great War was over, the armistice signed. But for one group of soldiers, the battles continued.

By Lara Zielin

On January 19, 1919, the snow was piled waist-deep outside the remote Russian village of Nijni Gorga. A raw wind was blowing across enormous drifts, plunging the temperature to negative 45 degrees Fahrenheit. The sound of exploding artillery shells and gunfire filled the air as 46 American soldiers from the 339th Infantry, Company A, fought a losing battle against 800 enemy troops – Bolshevik revolutionaries – sneaking through the snow dressed all in white.

The battle took place nearly two months after the armistice of November 11, 1918. Most American soldiers had already headed home. Those now actively fighting on the eastern front were bewildered by their predicament.

These fresh-faced soldiers – largely from Michigan and Wisconsin – had only just finished basic training the previous summer. In September 1918, they’d shipped out to England thinking they’d soon be fighting in France. But suddenly the 5,000 soldiers were issued Russian weapons and equipment, then sent via the White Sea to Archangel, a port 600 miles north of Moscow. They were told their mission was to help reopen the eastern front since Russia had left the war. Once the armistice was signed, however, the mission grew in complexity, ostensibly becoming one to return Russia to a government elected by the people after it was overthrown. The mission was nicknamed the Polar Bear Expedition.

“Soon it will be over, I hope, and I shall be back in the good old United States,” wrote Stillman Jenks, a corporal in the 339th, Company A, in a letter home to his family in Michigan. “I hope I never return to Russia.”

Overcome with Fatigue

Jenks was killed in what would be the most casualty-heavy battle of the Polar Bear Expedition, perishing along with 40 other men in the January 19 skirmish. Only six would make it out alive. Scores of bodies were left behind that day in the red-stained snow, and American casualties were scattered throughout northern Russia, according to the account of Walter F. Dundon, first sergeant of the 339th.

“We had lost a number of men killed and wounded,” he wrote. “Some wounded were sent back on [a] hospital ship; a number of dead were brought back when the troops returned in the summer of 1919, and about 100 other dead were buried in remote places scattered over an area covering hundreds of miles.”

The precise goal of the Polar Bears’ mission was never made clear. Prior to the armistice, the French and British governments felt the war was at a deadlock, according to a letter by Newton D. Baker, U.S. Secretary of War from 1916 to 1921. The French and British wanted to try for small military successes away from the heart of the war in Europe, in order to rally morale. He cited the capture of Jerusalem by General Allenby as an example of a successful side campaign. “President Wilson directed our participation in [the Russian campaign]…in a spirit of co-operation with our Allies in a matter about which they felt very deeply,” Baker wrote.

However, this letter wasn’t sent until 1924, when it was delivered to soldier Walter McKenzie from the 339th, trying to retroactively explain the rationale for the Russian campaign. At the time, the soldiers had no such information to alleviate their bewilderment. Confusion depleted morale, and “troops were described as ‘thoroughly overcome with fatigue,’” wrote Richard M. Doolen in Michigan’s Polar Bears: The American Expedition to North Russia (University of Michigan, 1965).

In the summer of 1919, eight months after the Great War had officially ended, the surviving men were finally taken out of Russia. When the troopship at last pulled into Boston Harbor, “a mighty cheer [went] up from the ship. It is all over now, we’re home,” wrote Clarence G. Scheu, a member of the 339th, Company B.

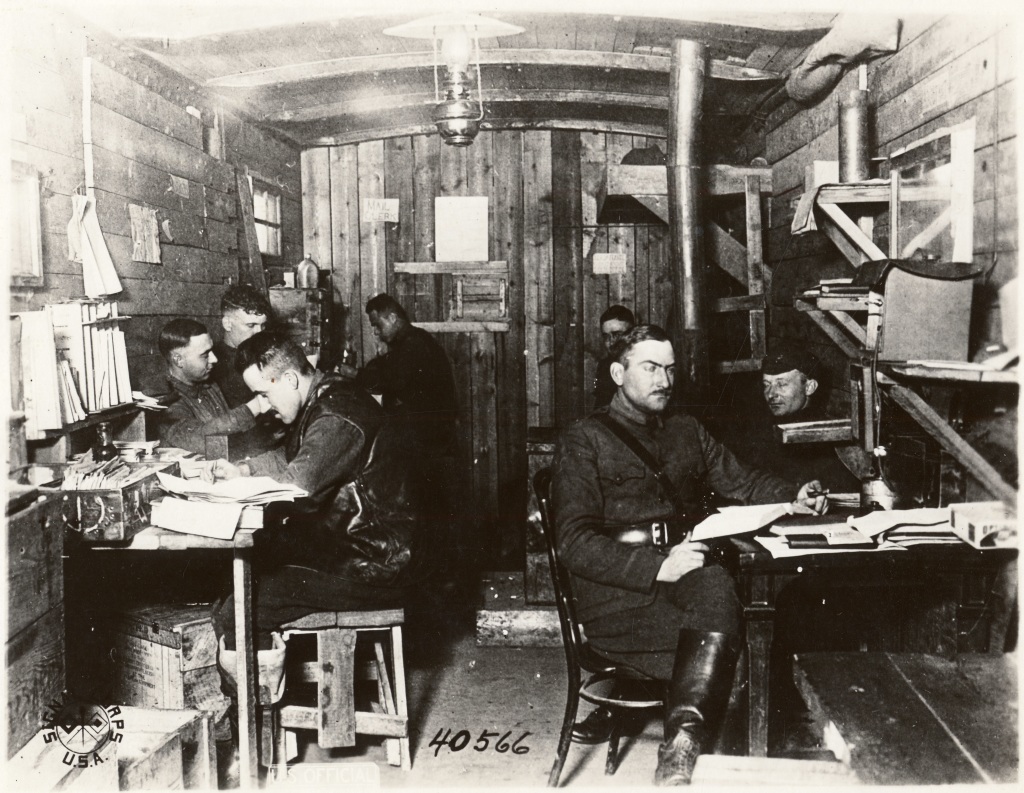

An old railroad car served as Polar Bear headquarters on the Vologda Railroad Front, Russia, November 1918.

Bringing All Our Boys Home

Three years later, the veterans of the expedition formed the Polar Bear Association, which met for the first time in Detroit’s Hotel Tuller on May 29, 1922. The stated purposes of the organization were to “preserve and strengthen comradeship” among its members, and to “perpetuate the history of our expedition and the memory of our dead,” according to A Compendium of the Life of the Polar Bear Association, published in 1958 by the association.

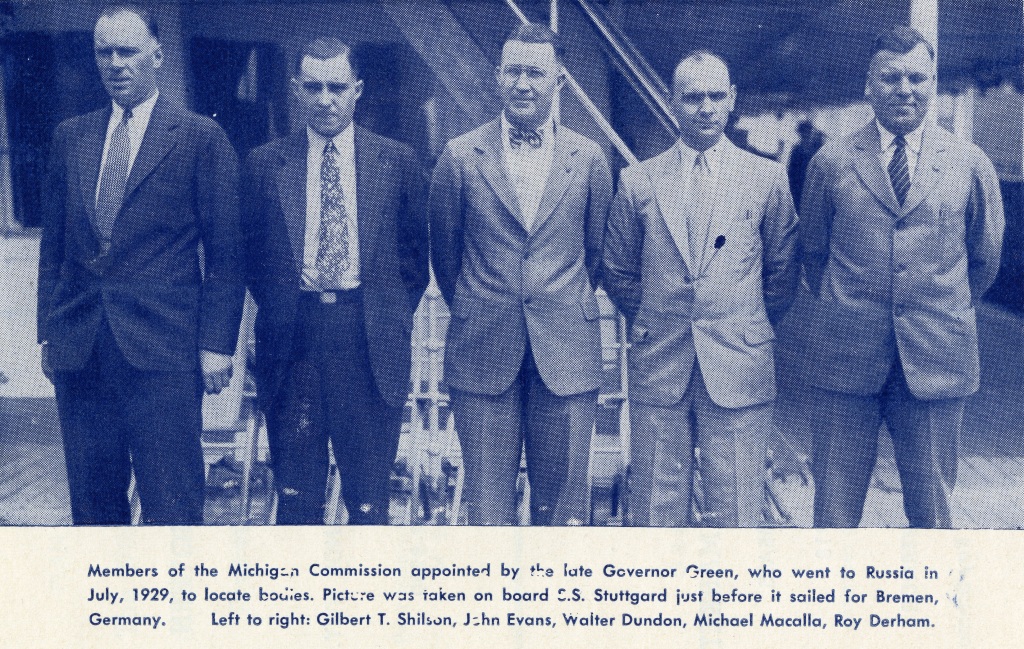

Another goal, if not explicitly written in the charter, was to recover the bodies of American soldiers lost on the Russian battlefield. Dundon helped organize and participate in a commission appointed by Michigan Governor Fred W. Green to return to Russia for precisely that purpose. He was backed by Michigan Senator Arthur Vandenberg, who called the Polar Bear veterans “faithful and unforgetting buddies” of the fallen.

On July 17, 1929, Dundon left Detroit and was on a steamship the next day, sailing across the Atlantic toward Russia. With him was Michael J. Macalla, also a member of the 339th, whose meticulous diaries showcase how – once the group made it back to the remote Russian villages where many of the battles took place – they needed to work with locals to find and exhume bodies.

In this entry, dated August 1929 from the village of Ust Padenga, Macalla describes how locals led them to mass graves:

“[Seventeen] men…missing in action…nobody knew what became of them. Our men found out from people in village. [One] man who took part in attack against them and woman where they were billeted. All said they were killed and taken about two miles down Padenga River from Ust Padenga about ¼ mile from churches on the right back of Padenga River. Found two big graves, one of [Bolsheviks] and the other Americans.”

Language barriers, culture shock, and exhuming bodies made for grueling work. In his diaries, Dundon illuminated the day-to-day difficulties and triumphs of finding soldiers’ remains:

August 17, 1929: “Today we dug for the first American. Finally found a button, it was English. All the people in the village, men women, and children, are watching us.”

August 22, 1929: “We did find two American crosses at Seletskae yesterday and believe others are buried there.”

According to Dundon’s papers, 86 bodies were recovered and brought back to the United States.

Soldiers arriving in Russia, September 1918.

Hearts at Rest

Newton’s 1924 letter to McKenzie cautiously acknowledged that the military campaign in northern Russia after the war was a strategic mistake. He wrote that someday, “when we come to understand the situation better and have more of the facts at our command,” he hoped that the United States would know with certainty that the service of the soldiers who perished was not in vain and was “in proportion to their numbers.”

In the meantime, the Michigan Polar Bears honored their fallen.

Forty-one bodies were reburied with honors in the Polar Bear Memorial at White Chapel Cemetery in Troy, Michigan, on Memorial Day, 1930.

In subsequent years, 15 additional soldiers would be laid to rest there.

Senator Vandenberg presided over the memorial dedication, having only a few months prior petitioned the Senate to print in the Congressional Record the names of the fallen. “There was little romance to soften the hard duty befalling these ‘Polar Bears,’” he said in October 1929 on the Senate floor. “It was desperate business amid the bitterest exposure. It was patriotism under acid test. If ever homage was deserved, it is by such patriots as these.”

The Vice President answered readily: “Without objection, it is so ordered.”

On that bright May afternoon in 1930, Dundon watched as the men he’d gone back to Russia to find were finally given full military honors.

“At the service, I was approached by a small elderly lady, who asked if I was the man who recovered her son’s body,” Dundon recalled in his typed reminisces. “I told her I had recovered all the bodies….She pulled my head down and kissed me through her tears and said, ‘This is the first time in 13 years my heart is at rest.’”

For more than 40 years, the Bentley Historical Library has actively collected the personal papers of officers and enlisted men involved in the Polar Bear Expedition. This includes Corporal Stillman Jenks’ photo, as well as the diaries, papers, and photos of Walter Dundon, Clarence G. Scheu, Walter McKenzie, and Michael J. Macalla. The Bentley also has Michigan Senator Arthur H. Vandenberg’s papers, as well as many other Polar Bear photographs, maps, and printed materials, all of which are available to the public.

Members of the Polar Bear delegation.