Magazine

The Life of Dr. Death

by Katie Vloet

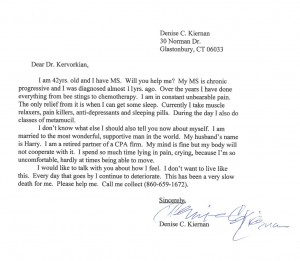

The writing on the letter is shaky, but the message is clear. “Dear Dr. Kevorkian, HELP! I am a 41 year old victim of MS. I can no longer take care of myself. Being of sound mind, I wish to end my life peacefully. I know I will only get worse. Please help me. Sherry Miller.”

The letter from 1990 is typical of the correspondence received by Dr. Jack Kevorkian, who, during his life—and even now, four years after his death—was the best-known advocate for physician-assisted suicide in the United States. People who suffered from incurable pain and untreatable conditions wrote to him and asked, begged, pleaded for his help. He was, they said, their only hope.

“Dr. Kevorkian, My son is dying of Lou Gehrig’s disease. … He would like your help to leave this world and free his soul to everlasting life,” wrote Carol Loving in another letter. After Dr. Kevorkian assisted in her son’s suicide, she wrote again: “It is impossible for me to express the blessing of your assistance and the gratitude I feel as a mother.”

These letters are part of a sweeping collection of Kevorkian’s papers, musical compositions, and artwork reproductions that were donated to the Bentley Historical Library in 2014 by the sole heir to his estate, his niece, Ava Janus. She made the donation at the request of Bentley Archivist Emeritus Leonard Coombs. The collection recently was opened to the public for research, including the files of 30 physician-assisted suicides. By his own estimation, Kevorkian assisted in the “medicides,” as he called them, of more than 130 terminally ill people between 1990 and 1998. The public called him “Dr. Death.” Those he consulted and their families called him their rescuer, hero, friend.

You Don’t Know Jack

Even before his medicide era, Jack Kevorkian was a controversial figure. Born in Pontiac, Michigan, in 1928, he grew up hearing his mother’s first-hand accounts of the 1915 Armenian Genocide, which she witnessed as a teenager. Anticipating service in World War II, which ultimately ended before he came of age, Jack taught himself German and Japanese as a teen.

Kevorkian’s intense coursework at U-M began in engineering, then moved to other disciplines, culminating with a medical degree in clinical pathology in 1952. After service in the Korean War, he returned to U-M for his medical residency, during which he became fascinated by death and the act of dying. He made regular visits to terminally ill patients, photographing their eyes in an attempt to pinpoint the exact moment of death and to help physicians understand when resuscitation was useless.

His proposal that death-row prison inmates be used as the subjects of medical experiments while they were still alive earned him the disdain of colleagues, the nickname of “Dr. Death,” and an ejection from the U-M residency program. Another proposal, that doctors transfuse the blood of corpses into injured soldiers, solidified his place as an outsider in the medical community.

The years that followed were marked by disputes with other physicians, frequent publication in medical journals, and ultimately an early retirement in the early 1980s, when he decided to focus on painting and composing music.

Years later, though, his interest in euthanasia was piqued after a visit to the Netherlands, where he learned about techniques used by Dutch physicians to assist in the suicides of terminally ill patients. He began writing again, this time about medicide, and he created a machine called the Thanatron (Greek for instrument of death) that could be used to self-administer a lethal dose of fluids. He advertised in Detroit newspapers for an “obitorium,” where terminally ill people could receive “death counseling.” Media attention led the first of his medicide clients, Janet Adkins, a 54-year-old woman with Alzheimer’s, to contact him.

In 1990, Kevorkian assisted Adkins in ending her life on a bed inside his 1968 Volks-wagen van parked in a campground near his home in Michigan. He then called the police, who arrested and briefly detained him. Like so many families that would follow, Janet Adkins’s family publicly thanked Dr. Kevorkian for helping to end her suffering.

Public Opinion and Physician Opinion

Jack Kevorkian became the most public person associated with the physician-assisted suicide movement for many years, as the numerous news clippings in the Bentley collection highlight. His haunting appearance, bizarre terminology for the tools and actions surrounding the medicides, and a seeming lifelong obsession with death made him a fascinating subject for the news media. And his public role in assisting with people’s deaths sparked heated debate about what has long been a controversial subject in the United States. “It’s thanks to my uncle that people have changed the way they feel about it and are discussing it with their doctors,” Janus says.

California’s governor just signed the End of Life Option Act, a measure allowing terminally ill patients the right to end their lives with a doctor’s help. According to Gallup Polls, the percentage of people in the United States who support euthanasia has risen from 36 percent in 1950, up to 65 percent in 1991, to a high of 75 percent in 1996, back down to 69 percent in 2014. Intriguingly, terminology appears to play a role in people’s perceptions; 69 percent in 2014 favored a law that would allow doctors to “legally end a patient’s life by some painless means,” but the number dipped to 58 percent when respondents were asked whether physicians should be allowed to “assist the patient to commit suicide.”

A noteworthy shift is taking place, meanwhile, in physicians’ points of view. The 2014 Medscape Ethics Report, a survey of 17,000 U.S. doctors, found that 54 percent of doctors surveyed think physician-assisted suicide should be per- mitted, up eight percentage points from 2010.

“I thought it was very significant to see that shift,” said Arthur Caplan, director of the Division of Medical Ethics at New York University’s Langone Medical Center and School of Medicine, in a Detroit News interview earlier this year. “The trend is clear—there’s more support among doctors, no doubt about it. This could change the legislative landscape.”

Part of the Family

Perhaps the most surprising portion of the Kevorkian collection at the Bentley are the photographs. Pictures of family reunions, picnics, get-togethers of all types. Jack Kevorkian attended these gatherings, but these were not his family members—not by blood, anyway. Countless families of Kevorkian’s clients became his champions, and his friends.

“They loved him and were his biggest supporters. He found a key to their soul,” says Olga Virakhovskaya, a lead archivist at the Bentley and the processing archivist of this collection. She says the decision was made to open all the medicide files to the public in part because restricting them would mean “hiding these stories and burying the experiences, even though the subjects have passed away and the families want their stories to be known.”

Family members wrote to him often, asking if they could assist with his legal bills as he stood trial, and promising to advocate for medicide to be legalized. “The families and those he assisted trusted him implicitly,” Janus says. “They were all very surprised that he wasn’t going to charge them. And he would be like part of the family. The family members would call themselves ‘survivors,’ but we would call them ‘cousins.’”

They stayed in touch with him even after he was convicted of second-degree murder in 1999 after having been acquitted three previous times. He served eight years of a 10- to-25-year prison sentence, then was released on condition he would not offer advice regarding assisted suicide or promote it, nor participate or be present at any person’s euthanasia. His colorful career would continue, though, with lectures at universities, a run for Congress, and TV interviews. In 2011, Kevorkian died at age 83 after suffering with kidney problems, liver complications, and pneumonia. There were no artificial attempts to keep him alive, and his death was painless, his attorney reported.

His legacy, however, lives on in books, artwork, movies, and the papers at the Bentley. Philip Nitschke, founder and director of right-to-die organization Exit International, has said that Kevorkian “moved the debate forward in ways the rest of us can only imagine. He started at a time when it was hardly talked about and got people thinking about the issue. He paid one hell of a price, and that is one of the hallmarks of true heroism.” The medicide files shed light on his legacy, including detailed documentation of each case, medical histories, questionnaires, forms signed by the patients’ medical doctors, and more. But forms and questionnaires don’t get at the heart of his relationships with the families. The greeting cards do a much better job of that.

“My family and I greatly appreciate your compassion in ending George’s pain,” says the handwritten note, one of many thank-you cards he received through the years. “You are truly a humanitarian doctor. Thank you, thank you.”