News Stories

Dancing My Dream

The collection of Warren Petoskey shines a light on the systemic mistreatment of American Indians, while also revealing the story of how one man found his spiritual calling.

by Mary Jean Babic

In Native American tradition, decisions are guided by the “seven generations” concept—humans must consider how their actions will affect the world seven generations out. People are but caretakers of the Earth, the thinking goes, and what they do is felt long after they’re gone.

By that same principle, any harm inflicted likewise reverberates for centuries.

Warren Petoskey, an elder of the Odawa and Lakotah tribes of northern Michigan, knows all too well about toxic inheritance. As a writer, speaker and teacher, Petoskey has devoted much of his life to coping with the historical trauma visited upon his people. Now 72, Petoskey lives with his wife, Barbara, in Charlevoix, Michigan, and runs Dawnland Native Ministries, which offers programs to address historical trauma and “exists to honor the Great Spirit and to bless the indigenous people of the land.” He’s also donated materials to the Bentley Historical Library, including an oral history, photos, and research for his published book, Dancing My Dream—all of which is digitized and available online.

Petoskey’s memoir, Dancing My Dream.

And yes, it’s that Petoskey: the upscale resort town in northern Michigan was named for his great-great-grandfather, Ignatius Petoskey, who ran a trading post and purchased 440 acres from the federal government on the southern shore of Little Traverse Bay. He wanted to establish a safe haven for his family and the Waganakising, the Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa, and especially to evade Jesuits who were pressuring the tribe to send their children to mission schools. The family and tribe eventually lost most of the land; the federal government never passed the deed of ownership to the state of Michigan, which sold some of the land to other buyers and claimed the rest for delinquent taxes that the tribe had no idea it owed. The town that flourished there still bears the Petoskey name, but the story of broken promises is one that’s all too familiar in American Indian narratives.

Boarding School Syndrome

The original blow to American Indians came with the arrival of Europeans in North America—or Turtle Island, as native people call it—and continued with centuries of massacre, displacement, and cultural destruction. (Petoskey has no objection to the word “Indian.” It was simply, he says, Columbus’s description of the Caribbean Taino as una gente in dios, or “a people of God.” This story will continue to use “American Indian” unless in a direct quote.)

Among the worst oppressors were boarding schools run by the federal government. Starting in the 1880s, American Indian children as young as six were shunted off to these schools to be “civilized”. The last American Indian boarding school in the United States closed in 1983. In that century, more than 100,000 students cycled through the brutal assimilation process. Children were forced to cut their hair, forbidden to speak their language or practice their religion, and denied contact with their families. Abuse was rampant. Students were beaten, sexually assaulted, and sterilized against their will; some died. “Kill the Indian, save the man,” was how Richard Henry Pratt, a military officer and prominent boarding school administrator, put it. The survivors returned to their families traumatized and, ignorant of their heritage and still facing discrimination by white society, unable to fit in anywhere. Many fell into addiction, depression and suicide.

Warren Petoskey’s aunt, Ella Jane Petoskey, was born in 1880, and Warren Petoskey calls her one of his “life teachers.” Her photo is part of Warren Petoskey’s collection at the Bentley.

The boarding schools come in for repeated condemnation in Petoskey’s papers at the Bentley. The centerpiece of the collection is Petoskey’s memoir, Dancing My Dream, a blend of autobiography and spiritual rumination. In the memoir, Petoskey blames boarding school trauma for his conflicts with his alcoholic, abusive father. Father and son fought constantly. When he was 14, Petoskey was “banished,” as he writes, to a family friend’s farm for most of a school year. He and his father reconciled in later years after his dad quit drinking, and Petoskey was able to put his father’s behavior into historical context.

“Dad was long removed from his culture—angry, frustrated, and in pain—and was medicating himself with alcohol,” Petoskey writes. “He had been stripped of his language, his land, his cultural origins and a loving relationship with his own father because of boarding school syndrome.” His father’s pain “was so deep-seated that he did not know how to expel it, and I became his target. One moment he was a loving dad, taking me hunting, fishing, or just playing around in the backyard. The next, he was knocking me around or forcing me to sit or stand by his chair for hours at a time. I was not to move or speak.”

It’s unclear if Petoskey’s father actually attended a boarding school. Some of his siblings had, as had his father and aunt, but he told his son that he had escaped that fate due to lack of beds. “But he may not have wanted me to know the truth,” Petoskey writes. “Whether my father attended or not, he exhibited all the dysfunctions mirrored in other boarding school survivors.”

Born in 1945, Petoskey spent much of his childhood in Stockbridge, Michigan, a farming community where his family were the only non-whites. He loved hunting and fishing, in part because the outdoors offered an escape from the prejudice he faced. When he was a high school junior, an American history teacher announced to the class, “We are going to study military geniuses like George Armstrong Custer and the dirty heathen savages that killed him!” Every head slowly turned toward Petoskey, who said, “I would appreciate it if you didn’t call my ancestors dirty heathen savages!” The teacher spent the rest of the year apologizing.

“God, Help Me!”

When Petoskey was 10 years old, a violent episode with his father resulted in a life-changing religious experience. His father, in a drunken rage, chased him around the house with a baseball bat, threatening to kill him. Terrified, Petoskey fled to a nearby vacant lot, raised his arms to the sky and yelled, “God, help me!” He had not been a churchgoer before this, but his love of nature had instilled a belief in a higher power. “Immediately, I felt a surge of energy around me,” he writes. “I felt suspended from the earth. …I felt a calling in my spirit that has remained to this day.”

Petoskey’s spiritual journey supplies some of the most fascinating reading in his collection. His wife, Barbara, was baptized in a Pentecostal church early in the marriage. (They wed four days after Barbara turned 16; he was 22.) Petoskey scorned her faith at first, even threatening to leave her and their toddler daughter, Diana. This seems strange in light of the vacant lot epiphany, but it wasn’t the only problem rocking their young family. Petoskey was following a little too closely in his father’s footsteps, drinking heavily and frequently staying away from home. He finally agreed to attend a church service—and broke down in tears. After that, Warren and Barbara devoted their lives to Jesus Christ. They went on to have six more children, and are still active in the ministry today.

But the Odawa in Petoskey never went into remission. He always spoke to the Creator rather than God. “When Indians were first introduced to Christianity we could not accept the idea of a Holy Trinity,” he writes. “I have come to know Jesus Christ as the visible image of the invisible Creator.” His wife was not always on board with his evolution, but grew to understand his life’s focus on historical trauma. Intriguingly, they discovered that Barbara’s great-grandparents were in the Trail of Tears, but no one in her family ever spoke about it. “The fact that she does not mention it,” Petoskey writes, “is an indication of the impact of historical trauma in her life.”

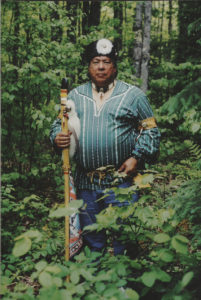

Petoskey in this undated photo from his Bentley collection.

Petoskey’s American Indian identity, while always present in some form or another, solidified over time. He was involved in American Indian education at Oakland Community College in the 1970s and served as personnel director of the Inter-Tribal Council in the early 1980s. Meanwhile, he served seven years in the Michigan National Guard and then had a career with the Michigan Department of Corrections as a warehouse manager.

After working in different places downstate, Petoskey was thrilled to return to the Upper Peninsula to run the warehouse of a new prison in Baraga. However, he encountered a hostile environment. Some of his coworkers referred to the flute and drum music he played in his office as “jungle music.” Petoskey often went by “Don,” for his middle name, Donald, and some of the prison workers called him “Don ho” (prison slang for “whore” and a purposeful misidentification of his heritage).

This was a marked contrast from a previous job at Cassidy Lake Technical High School in Chelsea, a now-closed minimum-security prison for young men, some of whom worked for Petoskey in the warehouse and wrote personal letters on his behalf. “He is a humanitarian by all meanings of the word,” wrote one man. “Mr. Petoskey has treated me like a human being is supposed to be treated,” writes another. “It did not bother him that I made a mistake.” But at Baraga, it was a different story. The stress led to a heart attack in October 1993, one afternoon while Petoskey was hunting.

He now looks at the heart attack as the event that forced him to reorganize his life around his American Indian identity. “I shed all the Western baggage I could, which included being Democrat or Republican, Protestant or Catholic. I wanted to live purely, as who I was and who I am. …I am Waganakising Odawa and that consciousness has made all the difference.” At age 62 he cut his first musical CD, Sacred Dream, “and I am told that it is good.”

Still, there is pain that will probably always remain. “It has been difficult to be happy,” Petoskey writes near the end of Dancing My Dream. “So much has been lost and can never be recovered. But I am a blessed man. …When my time comes to walk on, I know my spirit will return to its origin.”

The Warren Petoskey collection is open at the Bentley Historical Library and is available for viewing or research by the public. You can see the full finding aid for the collection, including digitized materials such as photos, newspaper clippings, and correspondence, online here.