News Stories

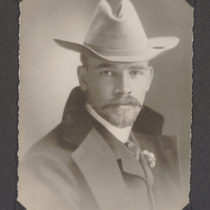

Mining for Adventure: the Story of Ocha Potter

Ocha Potter was a global adventurer and miner, with treks that took him from Anchorage to Africa. During the Great Depression, he plotted to save the economy of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula through tourism. His full story, from wilderness to wealth, can be found in his papers at the Bentley Historical Library.

by Mary Jean Babic

If you’ve ever swung a nine iron at the Keweenaw Mountain Lodge in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, or taken in the breathtaking views of Lake Superior along Brockway Mountain Drive, you’ve experienced the legacy of Ocha Potter.

In the opening decades of the twentieth century, Potter was a central figure of Michigan’s copper industry, serving as a mine superintendent in the Keweenaw Peninsula, the very northernmost tip of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. After the Depression hit, closing the mines and sending unemployment soaring above 80 percent, Potter looked around at Copper Country’s natural beauty and envisioned an economic lifeline: tourism. Soon, the woods rang with the sound of out-of-work miners building a golf course, lodges, and scenic drives—funded by federal and state relief programs but Potter projects, all. “There’s a feeling now up in northern Michigan,” one local newspaper wrote after the golf course opened, “that even if the grey-coated mine stiples do turn rusty with idleness, the ship won’t be lost.” It wasn’t, and from those seeds grew the tourism industry so vital to the region today.

Before he settled in the Upper Peninsula, however, Potter’s early adulthood unfolded like something out of an adventure novel, with mining jobs taking him from the jungles of west Africa to the icy rivers and glaciers of Alaska. Between excursions, he cobbled together a mining engineering degree from the Michigan College of Mines (now Michigan Technological University) in Houghton.

In 1938, when Potter was sixty-one, he started penning his memoirs at the urging of his four children. The result, 60 Years Plus 12, is a cornerstone of the Ocha Potter collection at the Bentley Historical Library. Potter’s collection also includes newspaper clippings, family correspondence, and scrapbooks from his globe-trotting. Through the materials, a profile emerges of an independent thinker with a dry wit who believed in progress and business and civic duty; felt loyal toward the men who worked for him; didn’t especially like having his ideas challenged; and held a low opinion of government bureaucrats, union rowdies, and rabble-rousers in general.

From Wisconsin to the World

Descended from Yankee pioneers who had settled in central Wisconsin before the Civil War, Potter was born in 1878 in Sherwood, Wisconsin. He was raised by a single mother he described as “a very large woman with a strong sense of humor,” who was “independent and in some ways, eccentric.” Evidence: She named one son Ocha, which she’d read in an encyclopedia (“some historic Persian or Arabian general,” he wrote), and another son Gift. For all the loving description Potter includes of his mother, however, one name that strangely appears nowhere in the book is hers.

Julia Silverfriend, age 16. She would marry Ocha Potter in 1904.

Potter dedicated the memoir to his wife, Julia (nee Silverfriend), “a slip of a girl with black hair and big brown eyes,” though her first name doesn’t appear again until the last page of the memoir. She is referred to simply, at first, as The Girl and then later as “my wife” and “Mrs. Potter”. They met in high school and, when Potter left Wisconsin in 1898 to enlist in the Spanish American War, Julia kissed him goodbye at the train station. They didn’t see each other again for nearly five years, when they reunited in Denver. They eloped in 1904.

Those five years took Potter far from his small-town roots. After joining the army, he was stationed in Tennessee and South Carolina, sending dispatches back home to a Wisconsin newspaper. Most of his reports centered on the travails and hijinx of a soldier’s life, and he never saw action in the war. On the day his regiment shipped out from Charleston, he was diagnosed with typhus. “That ended my army career,” he wrote. “I had not seen a rifle cartridge—much less fired one.” He and other sick troops were quarantined for months on a hospital ship. “Each day near noon the ship stopped,” he wrote. He’d hear shuffling overhead. “Finally an elongated white object would flash by the open door outlined against the sea and the sky. A splash. Taps. Another boy had given his all for his country—victim of ignorance, stupidity, politics.”

After recovering, Potter found work as a laborer in a copper mine prospect near Houghton, and thus stumbled onto his lifelong career. He caught an early break on a job using a diamond drill to look for a copper vein near Calumet. Diamond drilling was new at the time, and anyone with experience was in high demand. Potter soon found himself on a ship headed to the jungles of present-day Ghana (then called the Gold Coast, a British colony in west Africa), hired to man a diamond drill for gold exploration. In Ghana, he sampled snake meat, encountered a leopard, and battled army ants. “Parrots chattered, birds screeched, animals howled or barked, and always through the night came the throb and the beat of distant drums. It made an everlasting impression on a lonesome homesick Wisconsin farm boy.” After ten months, malaria felled him. It was back to the U.S. for convalescence and a period of aimless wandering that culminated in a written proposal to The Girl. She accepted.

After their marriage, Potter had completed a single semester of college when a professor made him an offer to lead an expedition in Alaska. A “wild-eyed prospector” thought he knew where a mountain of copper lay, and he had financiers in Michigan backing the project. Potter, knowing nothing about Alaskan exploration, accepted. With zero assistance from the prospector, he organized a team and supplies, and in January 1905 they sailed from Seattle to Valdez, Alaska. From there, the group spent more than two months transporting supplies overland and up icy rivers, terrain that could hardly have differed more from the jungles of western Africa. Potter had the full-on Alaskan experience, fording rivers and subsisting on salmon and visiting American Indian camps. He hunted a bighorn sheep, whose mounted head hung in the Potter family home for decades.

Valdez, Alaska, photographed during Potter’s trip in 1905.

Throughout the arduous trek, Potter was impatient to see the “mountain of copper which was to enrich our backers, enable me to complete my college education … and assure my financial independence.”

The big day arrived. “One look,” Potter wrote, “and my world collapsed.” The “mountain” was nothing more than “a few inches of ore spread on the face of a ‘fault’ in the formation.” Potter returned to Michigan in August 1905, empty-handed. But his backers still thought there might be copper in those same hills, so the following January, leaving his wife and newborn son in Denver, Potter headed back to Alaska, this time for twenty months.

The second stay was rife with drama. At one point Potter killed a mama bear and one of her cubs, whom he had startled on a trail. He left a second cub crying in a tree because “I had had enough of murder.” Potter kept the skins, though, sending them on with a prospector he’d met. The prospector, wife and child in tow, was returning to civilization and said he’d mail the skins to Potter’s wife. The skins never made it. The family’s boat capsized in the treacherous rapids of the Nizina River, and they all drowned.

Amid the tragedy ran veins of humor. One night, Potter awoke to find his pants, which he had set by a fire to dry, ablaze. “We were 40 miles out from headquarters with 120 miles yet to go—and I had no pants.” Ever resourceful, he cut leg holes into a gunny sack, secured the waist with a piece of cloth and, with red long underwear sticking out, called it good. The expedition ended with Potter staking a few claims on a hunch that, despite published reports by professional geologists to the contrary, the claims sat atop a sizable copper lode. After another semester of college in Houghton, he went back to Alaska a third time to further survey the claims. On this trip, Julia and their three-year-old son George came along. Potter was plainly proud of their hardiness. They made the return trip on a homemade boat down three swift rivers, at one point navigating the dangerous rapids in the Nizina River where the prospector and his family had perished two years earlier. After passing through safely, the Potters paid respects at the family’s riverside graves. Julia and George, Potter noted, were likely the first “white woman and child” to successfully run the Nizina rapids.

With the second look at the copper claims, Potter changed his mind and concluded that they were useless. Dejected, he advised his bosses to accept an offer from another company to buy the claims for a modest price, ending his Alaskan enterprise on a flat note. Only years later did Potter learn that his original hunch had been right after all: the claims were loaded with copper and had gone on to pay the new owners millions. “[J]ust how many millions,” Potter wrote ruefully, “I have never quite had the heart to learn.”

Mining and Michigan

Potter and Julia settled in Ahmeek, Michigan, adding three daughters to their family. In October 1909, Potter became a mine superintendent of Superior Copper Company, a small mine near Houghton controlled by the Calumet and Hecla Copper Company, for whom he’d work until his retirement in 1948. At the Superior mine, he found an operation with almost no safety procedures in place. In one thirty-day span, four men were killed. Mining had always been hazardous, but Potter was determined to improve safety.

“Our own safety department was originated,” he wrote, “when I came up alone from the mine one morning with the body of an old employee at my feet and his head in my arms.” He developed a safer process for “stoping”—mineral extraction that leaves behind an open space—and introduced one-man drills, winning the cooperation of employees who accepted less pay per unit of work but, thanks to increased efficiency, made more money overall. By 1912, all the company’s mines used the one-man drills, which stayed in place until the ore deposit ran dry.

If health hazards are a fact of mining life, so are strikes. Potter described the arrival of the Western Federation of Miners in 1913 almost as an invading force. “Sluggers and intimidators from Butte and other western mine camps flooded the district.” Less than 10 percent of the 13,000 copper miners belonged to the union, he insisted, “but those who wanted to work were cowed by organized mobs.”

In fairness, he blamed both sides for inciting disorder: “The mine managements shut down the mines and imported professional private police who were just as bad as the union agitators.” Potter may have frowned upon violence, but when “a mob of strikers and agitators” showed up at his office, he and two colleagues met them with steel rods in their hands. “I had caught a man by the collar of his shirt with one hand and was twisting it to choke him and at the same time trying to protect myself with my other hand. Suddenly a young lady sank her teeth into my bared arm. We won the skirmish,” he concluded coolly, “with no serious casualties on either side.”

Independence Through Tourism

It was in 1932 that the bottom dropped out of the Keweenaw Peninsula. Jobs and savings vanished virtually overnight. Though he didn’t know it then, the Depression would usher in the major, final act of Potter’s life. He ended up in charge of all forms of relief, whether from company, county, state or federal sources. How that came to be isn’t clear, but Potter wrote of his sense of obligation: “Because most of the men thrown out of employment had been working many years under my supervision, I had a feeling of personal responsibility for their welfare.”

He viewed relief as charity, shameful as anything more than a temporary state. Taking sober stock of Keweenaw—very few farms, scattered fisheries, almost no industry outside of mining—he decided that the region’s most and perhaps only bankable assets were beautiful scenery and mild summer weather. He believed that the relief funds flowing into the region should go toward developing a tourism industry “to in some measure enable our people to become again independent, self-respecting citizens.”

Julia and Ocha Potter at the New Orleans Country Club in 1923.

In the next few years, Potter operated as something of the Robert Moses of the Keweenaw Peninsula. His first plans were for scenic highways along lake shores and over mountains. The county road commission granted 40 miles of right-of-way for the projects; it surely helped that Potter himself sat on the commission. He praised the diligence of the workers building the road, but not without getting in a dig at President Franklin D. Roosevelt: “The men had not yet become saturated with the New Deal philosophy emanating from Washington and they worked cheerfully and well.”

Potter next set his sights on a golf course, which in his opinion every high-class resort town needed. A local mining company donated 167 acres on a high plateau overlooking Lake Superior about one mile south of Copper Harbor. Potter then went to Lansing and persuaded the state government to cough up another 160 acres. Workers cleared away trees on the land, saving large trunks to build “a pretentious clubhouse”. Potter bought books on golf course design and laid out an 18-hole course himself.

All the projects required approval from the Civil Works Administration, a New Deal job-creation program that preceded the Works Progress Administration. Everything was moving along nicely, Potter wrote, until a bunch of federal muckety-mucks started butting in. “Speeches from the White House caused class prejudice to rear its ugly head.” (The man really did not like FDR.) “Soon there were mutterings that golf was a rich man’s game and the sentiment spread that advantage was being taken of the working man’s misfortune to provide a playground for the wealthy.” Others mocked the idea of planting a golf course way up in the remote reaches of Michigan, dubbing it “Potter’s Folly.”

Fed up, Potter quit and went to California for a month. When he came back, he resumed his relief work (done, as before, on a volunteer basis), but soon a strike broke out among the workers building the golf course. “Have you ever faced 350 angry men—alone?” Potter wrote. “Well, I have. And it isn’t pleasant.” State and federal officials asked him to resign. He refused. They sacked him. “Paid professional social workers took my place and our people became ‘clients.’”

But he was still on the road commission. With the help of another member and the state relief administrator who sympathized with them, they were able to finish the golf course—nine holes at least. The head of the bighorn sheep Potter had bagged in Alaska hung, for a time, on the clubhouse walls. In 1937, the first year of operations, the course turned a small profit. By 1938, it attracted some 80,000 visitors. Opposition fell away, and Potter was vindicated. In 1940, the area got an additional boost with the opening of Isle Royale National Park in Lake Superior, seventy miles north off the coast. As the perfect jumping-off point, the Keweenaw Peninsula stood ready to start ferry service and launch other businesses serving visitors to the new park.

The events with the golf course were still fresh when Potter wrote his memoir, and his frustration with the whole process burns across the page: the infinite paperwork, the seemingly arbitrary decisions and reversals of decisions, and, most of all, the absolute lack of business sense on the part of the government agents with whom he was forced to deal. “Invariably they have been trained by professors as ingenuous as themselves—the blind leading the blind. Both are essentially spenders. … In Keweenaw the miracle has been that we have accomplished so much with the handicap of federal methods.”

By the time Potter died in 1955, summer homes had been built along the shores of Lake Superior and more resorts had opened. Grocery stores, hot dog stands, cocktail bars, charter fishing boats, and souvenir shops, flush from the steady flow of tourists, were thriving. Copper mining put the Keweenaw Peninsula on the map; tourism kept it there. Ocha Potter had a major hand in both.

The scrapbooks in Ocha Potter’s collection have been digitized and can be found here. More on the collection overall can be found in the online finding aid.