Magazine

Writing Aunt Lulu

by Cinda Nofziger

In 1943, Lulu Brown Middleton, a farmer’s wife from Lake Orion, Michigan, read the names of World War II service men listed in her local paper. “I just think I’ll write to them,” she thought. And so began what became a massive undertaking.

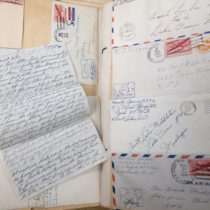

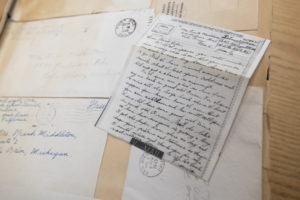

By the end of the war, Middleton had corresponded with more than 500 service men and women, primarily from Lake Orion and Oakland County, Michigan. She carefully saved their letters, still nestled into their envelopes, in five scrapbooks—four of which are now housed at the Bentley Historical Library.

The scrapbooks contain approximately 1,300 letters, plus photographs and mementos sent from the war. The collection reveals a woman who cared deeply about connecting with young people, many of whom she hadn’t met, but to whom she still became family. “Just as soon as you are in the service, I automatically become your Aunt Lulu, so of course I know you and I hope you feel acquainted with me,” she wrote.

Through “Aunt Lulu,” these Oakland County service members learned about home, even as they moved around European and Pacific theaters. The majority of the letters in her scrapbooks come from men, whom she called her “nephews,” but Middleton also wrote to her “nieces.” She wrote to hundreds of soldiers, sailors, pilots, nurses, Women’s Army Corps volunteers (WACs), Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service members (WAVES), and other military personnel.

From Recipes to Reserves

The Lake Orion Weekly Review, Middleton’s local paper, was the connective thread in Middleton’s correspondence. She would send the paper the letters she got from service members, and the paper would reprint excerpts, sometimes with Middleton’s comments included. Middleton would at times reply to a letter through the paper itself. The public correspondence was a way for Middleton to let the community know whom she’d been writing to and whom she had heard from.

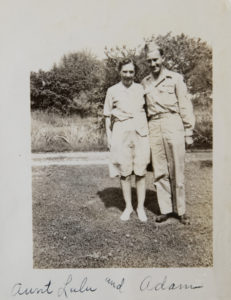

Lulu Middleton poses with a soldier named Adam in a photo from one of her five scrapbooks archived at the Bentley.

The public correspondence went far beyond Lake Orion. The local American Legion Charlton Polan Post 233 sent the Weekly Review to “every service man and woman from Orion and Oakland Township,” according to an article published in 1964. In this way, Oakland County service members learned about home and stayed in contact with each other, even as they moved around Europe and the Pacific.

Middleton was the perfect person for the job. Born in Orion Township in 1881, she never strayed far from the area. She was educated at Pontiac Normal School, then became a teacher. She married Frank Middleton in 1908. Together, they raised three sons and owned a 200-acre farm. She was active in her church and various clubs, and, before the war broke out, had been submitting content to the local paper for years—in the form of recipes.

A Beautiful View

In May 1943, Middleton began corresponding with Private Perry Galpin when he was stationed at Camp Gordon, Georgia. Galpin lived in Pontiac until he joined the Army, but his parents had moved to Lake Orion, which is how Middleton began writing to him. They continued to correspond as Galpin’s unit went to North Africa on its way to Italy. There, he fought in the Battle of Anzio beachhead, then moved to France, where he helped “clean out the Colmar Pocket” before he “finally got” to Germany.

Over the next two years, in approximately 80 letters, Galpin shared some of his experiences, reflections, and memories of home with Middleton. “It really makes a person feel a lot better to receive a letter like the one you wrote to me,” he told Middleton while he was in North Africa in 1943.

Perry Galpin corresponded with Middleton throughout the war.

Galpin was often careful to note how long it had been since he’d received mail, or how many other letters he needed to send. Frequently, he was low on paper, and usually asked Middleton to send him more. Otherwise, he’d have to send letters on “V-mail,” a special type of mail designed to take up less weight and space during overseas transport. Writers would use particular paper to compose their missives, then those papers would be microfilmed. They’d be carried to the U.S., where the letters would be printed, but they ended up very small—almost illegibly so. Galpin, and others with whom Middleton corresponded, complained about using V-mail and worried that it would be hard for their friends and relatives to read.

Galpin and Middleton sent each other jokes in their letters, and traded reminiscences about the Orion and Plymouth areas. Sometimes, Galpin would write descriptions of places he remembered from home. In a V-mail from April 1944, he writes about looking out from a hill between Orion and Rochester. “Just before dark, when the sun is setting, it is a beautiful view to see when everything is fresh and green in the spring.”

Occasionally, Middleton and Galpin would discuss other servicemen from home whom they both knew. In December of 1944, he talked on the phone with his pal Sam Burman, another “nephew” of Middleton’s and a Lake Orion resident. Galpin and Burman made plans to meet as they were in the same area, but Burman’s unit moved before Galpin got to him.

Galpin almost always described the places he was when he wrote—whether that was in an older couple’s home in France, or on guard duty with the paper in his lap. In a foxhole on an Anzio beach, he wrote, “we have a mouse or two that eats our C-ration crackers.” In France, he wrote, “today you would find me in the kitchen of a house, along a rail road track. An old couple lives here and at this time, mamma is sitting in a chair with her [head] bent over catching a few winks of sleep. Papa, likewise only he is in a[n] arm chair where it is more comfortable. His book and glasses are on the table in front of me. Outside it is raining and blowing and really dark.”

Almost Like a Mother to Me

They also sent each other more than letters. Middleton sent Galpin blank paper, candy, and cookies in care packages. Galpin wrote a thank-you message for some maple candy that Middleton had sent. They exchanged photographs. Galpin sent samples of money back from the var – ious places he was stationed, an armband from the Hitler Youth movement, and cans of sand, an easy-to-get souvenir during a tough time.

Galpin and Middleton became close, as revealed through the more intense and sometimes difficult conversations they had. Middleton asked for advice about what she should say to soldiers she met on the streets, and Galpin asked for advice about his girlfriend, who wanted to live in the country, while Galpin wanted to remain in Pontiac. The two broke up.

Galpin also revealed to her how scared he was in letters written from the Anzio beachhead, the location of a months-long battle of Allied forces against German and Italian troops for control of Rome.

In April 1944 he wrote, “[A] short time ago I was crawling in here while some shells were exploding nearby. All during that time I was saying a silent prayer to myself.” About a month later, he wrote, “Well Aunt Lulu, yesterday I just missed death by 3 minutes and I sure thanked God for keeping me safe. I just broke down and cried when I found out what happened. I can’t say more than that because of the censorship, but this morning I am still nervous about the thing.”

Later, Galpin apologized for sharing so much. He wrote, “I guess when you don’t know who will get it next that you start talking all you know.” But through it all, Middleton provided a sounding board for Galpin, even as he struggled with telling stories and describing how those moments felt.

“I spill my feelings on to you once in a while and you come right back to me almost like you were a mother to me,” Galpin wrote. Galpin continued to write to Lulu until he returned to the U.S. in 1945. His last letters to her are Christmas cards, sent from Pontiac.

Galpin continued to live in the area. He married and raised two children. For 25 years, he drove for GM Truck and Bus before retiring in 1987. He died in Rochester Hills, Michigan, in 2018, at age 95.

A Look Inside

Middleton kept the letters and envelopes from her “nieces and nephews” in carefully constructed scrapbooks. The pages are organized somewhat chronologically and include maps—of the United States, Europe, Asia, and the world on which she marked the locations of her correspondents. She listed their names and where they were stationed.

Her scrapbooks also include some of the souvenirs that her correspondents sent, including paper money, badges and patches, cartoons, newspaper clippings, and photographs. These artifacts provide a rich look into the lives of individual service men and women during World War II. They offer insight into soldier’s experiences and thoughts as they served in various capacities around the world.

Her scrapbooks also include some of the souvenirs that her correspondents sent, including paper money, badges and patches, cartoons, newspaper clippings, and photographs. These artifacts provide a rich look into the lives of individual service men and women during World War II. They offer insight into soldier’s experiences and thoughts as they served in various capacities around the world.

The Bentley Historical Library acquired the collection in 1964. Middleton passed away in 1969 and was buried in Eastlawn Cemetery in Lake Orion.

Lulu Middleton’s scrapbooks are open to the public.