Magazine

Milliken in the Middle

Michigan’s longest-serving governor was a Republican renowned for reaching across the aisle to Democratic colleagues, and for making Michigan’s environmental health a priority. His collection at the Bentley reveals a breed of politician that’s nearly extinct.

By Robert Havey

Flags in Michigan were flown at half-staff for 14 days after William G. Milliken died on October 18, 2019, a day of mourning for each year Milliken served as Michigan’s governor (1969-1983).

“He had a unique ability to bring people from both sides of the aisle together for the betterment of Michigan,” said Governor Gretchen Whitmer about her predecessor. Milliken was a “true statesman who led our state with integrity and honor.”

These sentiments were echoed by people across the political spectrum. A lifelong member of the Republican Party, Milliken had a reputation for being willing to work with Democratic colleagues and even earned the respect of defeated opponents. Sander Levin, who lost the 1970 and 1974 gubernatorial elections against Milliken, said that he “retained respect for [Milliken] after the campaigns, and the years since have vindicated that.”

Milliken’s 14-year term as governor is the longest in Michigan history. Term limits were added to the state constitution in 1992, making this record unlikely to be broken. However, as his archived collection at the Bentley shows, all was not perfect in Michigan during Milliken’s reign. Violence and unrest in Detroit, cascading environmental disasters, and oil shortages made Michigan a tumultuous place to build a political legacy.

Traverse City and Back Again

Milliken’s name was already famous in Traverse City when he was born on March 26, 1922. His grandfather founded the city’s largest department store, J.W. Milliken, Inc. Both his father and grandfather served as state senators. His mother was the first woman elected to public office in Traverse City when she joined the school board.

Following in his father’s footsteps, Milliken enrolled at Yale with the expectation he would return to take over the family business. The attack on Pearl Harbor and the outbreak of World War II during Milliken’s sophomore year put an end to his neat plan. Milliken enlisted in the U.S. Army Air Forces in February 1943, and in short order was shipped off to fight in Italy.

During his 50 combat flights as a B-25 waist gunner, Milliken experienced two crash landings and was wounded when flak from an anti-aircraft round hit him in the torso. His service earned him many accolades, including an Air Medal and Purple Heart.

After the war, Milliken finished at Yale and married the love of his life, Helen Wallbank, whom he had met at a party before leaving for Europe. They had plans to move to Ann Arbor after Milliken was accepted to the University of Michigan Business School, but news came from Traverse City that his father was seriously ill.

Milliken returned home and became the third generation to run the family store. It was the path laid out for him, but Milliken yearned for a career in public service. “It wasn’t my dream, but I felt an obligation to help my father,” he recounted in a 2003 interview with his biographer.

The Road to the Governor’s Mansion

Milliken started his career in electoral politics in 1960 by winning the Michigan State Senate seat previously held by both his father and grandfather. In 1964, over mild reluctance from the incumbent Governor George Romney, Milliken was chosen by Michigan’s GOP to be their candidate for lieutenant governor. The election was a landslide victory for Lyndon Johnson and Democratic candidates for the State House and Senate, but Michigan picked the Republicans Romney and Milliken for the top state offices.

The relationship between Romney and Milliken was cordial but never warm. They worked in very different ways: Romney was instinctual and decisive, whereas Milliken liked to find consensus. “Frankly, except as required by law and circumstance, there was no personal relationship between those two governors,” said a former Milliken aide.

Governor Milliken at a microphone with people crowded around him, 1978. HS9505

The two men’s iciness became less of a problem as Romeny’s attention turned to national politics. As a popular governor in an important Midwest state, Romney was considered a leading Republican candidate to challenge President Lyndon Johnson in the 1968 election. Romney delegated more and more of the business of running Michigan to Milliken.

Then, on July 23, 1967, a Detroit police raid of an unlicensed bar escalated into a week of rebellion and violence. By July 27, 43 people had been killed and more than 7,000 arrested. The civil unrest would be a defining moment in Detroit’s history. Romney’s hesitation to call in National Guard troops to quell the situation drew much criticism, not least of which came from his potential presidential rival Johnson.

In a 2003 interview, Milliken said that at the time he saw the violence as a failure of politicians to address underlying problems. “What came out of the riots was an opportunity to consider what caused them in the first place. The plight of the Black population [in Detroit] was finally seen as something to get damned serious about.”

Romney lost the Republican presidential primary to Richard Nixon, but was picked by Nixon to be secretary of housing and urban development. Milliken was now, at last, governor.

Un-Pure Michigan

Growing up in northern Lower Michigan sparked a life-long love of nature in Milliken, but also exposed him to the costs of unchecked industry. Zealous logging in the 1800s denuded many of Michigan’s old-growth forests—damage that was obvious even more than a century later.

On January 22, 1970, Milliken issued a 20-point environmental policy plan. “Unless we move without delay to halt the degradation of our land, our water, and our air, our own children may see the last traces of Earth’s beauty crushed beneath the weight of man’s waste and ruin.”

The Milliken administration was the first state government to ban most uses of DDT, which had been found in alarming levels in Michigan salmon. In 1970, Milliken signed into law the Michigan Environmental Protection Act, which enabled citizens to sue polluters.

Bottles litter Michigan Stadium in 1969. Photo by Robert Kalmbach, BL018892.

Milliken’s was the first signature on the “Bottle Bill” petition, which instituted a 10-cent deposit on recyclable containers. The bill was enacted in 1976 and became the model for similar bills in other states.

Not every environmental problem had a happy ending. In 1973, the Michigan Chemical Company out of St. Louis accidently shipped bags of the fire retardant PBB (polybrominated biphenyl) to the Farm Bureau Service, where they were mixed with feed and sent to farms across the state.

The result was disastrous. PBB is toxic and a carcinogen. After the contamination was discovered, 23,000 cattle and 1.5 million chickens from 500 Michigan farms had to be destroyed. But people had been eating contaminated food for months, not realizing it, even as farmers sounded the alarm. Today, PBB levels in people from Michigan are still elevated and are linked to increased risk of breast and digestive cancers.

Blame fell on the government for the tragedy, in no small part because of a perceived lack of urgency after farmers raised concerns. Later, Milliken expressed regret about his failure of communication about the disaster: “I wish I had more effectively carried the story to the public as an educational issue. I didn’t adequately explain what had happened.”

Across the Divide

Milliken worked to mend the divide between Michigan’s government and Detroit. Tensions were still high in the aftermath of the rebellion in 1967. But Milliken found support in the most unlikely form: Coleman Young, the brusque Democratic mayor of Detroit.

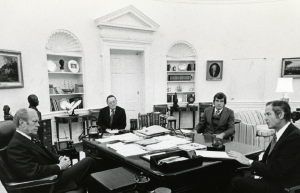

Governor Milliken (far right) meets with President Ford (far left) in the Oval Office in 1976. HS19510

Despite their differences, Milliken and Young found common ground in their dedication to public service. Young had also served in WWII, as a member of the Tuskegee Airmen. Each believed that good-faith efforts by the government could make people’s lives better.

Milliken and Young’s biggest joint project was the Detroit “equity package,” a plan to give state funding to institutions in Detroit that benefited all of Michigan. The Detroit Institute of Arts, Public Library, and Zoo all received state funding for the first time.

“As I look back on Coleman Young and that relationship, I consider that to be one of the most meaningful and important friendships and alliances I had in my entire 14 years as governor,” said Milliken in 2004. “We were able to work together constructively to solve critical problems, and I think that’s what the state needed.”

Ringing Endorsements

In 1981, Michigan’s economy was in shambles. Unemployment had risen to 12.5 percent. James Blanchard, a Democrat and Milliken’s gubernatorial successor, often pointed out that Michigan had more unemployed workers than other states had people. Milliken announced on December 22, 1981, that he would not seek a fifth term.

Even in retirement, Milliken continued to talk to reporters about the issues of the day. He increasingly found himself at odds with the Republican Party and partisan politics in general.

Milliken made headlines for endorsing the presidential bids of Democrats John Kerry and Hillary Clinton and the gubernatorial campaign of Jennifer Granholm.

A public memorial service for Milliken is being planned for May 2020. Friends, family, and admirers of every sort are expected to attend.

The William G. Milliken papers are open to the public.

Sources for this story include:

The William G. Milliken papers. The Helen W. Milliken papers. The George Romney papers. Dempsey, Dave: William G. Milliken: Michigan’s Passionate Moderate (Petoskey Co-Pub, 2008).

The Evolution of Helen Milliken

Helen Milliken reviews a prototype for Artrain, a mobile art museum that traveled throughout Michigan for more than 30 years.

In a 2003 interview, Helen Milliken said that her awakening to the issues of women’s inequality was her “second great education.”

Helen was raised in a traditionally conservative household in Colorado. She left to attend Smith College, where she graduated in 1945. That same year, she married William Milliken when he came back from WWII, a partnership that lasted until her death in 2012.

In that time, she went from being the supportive wife of an up-and-coming GOP star to a political force in her own right.

When the Millikens first moved to Lansing after William became Lieutenant Governor, Helen became a champion for the arts, supporting the Michigan Council for the Arts and Michigan Artrain, a mobile art museum that traversed the state on rails. (The rail museum was retired in 2008, but Artrain Inc., headquartered in Ann Arbor, still exists today.)

During Milliken’s second term, Helen expanded her interests, taking on the more politically charged issues of environmental protection and women’s rights. She organized garden clubs across the state to support the Bottle Bill petition. She spoke out against oil drilling in the Pigeon River area: “It seems to me this public land should remain unspoiled, a part of the heritage of all the people of Michigan.”

Helen became co-chair of the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) committee in 1979. When Gov. Milliken brought the Republican National Convention to Detroit in 1980, Helen was not at her assigned place alongside him at the opening ceremonies; she was outside of Joe Louis Arena, protesting the GOP’s decision to remove its support of the ERA from the party platform.

In a 2006 interview with the Associated Press, Helen expressed concern that young women were shying away from feminism. “They don’t know their history,” she said. “Young women take so much for granted now.”

The Helen W. Milliken papers are open to the public.