Magazine

Filling in the Silences

Incarcerated individuals are some of the last people to have their stories and experiences archived. The Bentley is working to change that by partnering with U-M researchers on a new initiative that will preserve some of least-heard voices in Michigan.

by Lara Zielin

Jose Burgos can tell you when he found joy in prison.

It was 2003, and he was 12 years into a sentence of life without parole. All his appeals had been denied, and he was serving time in a maximum-security facility in Standish, Michigan. He was isolated from the general prison population in what’s called “segregation,” and with him were mentally ill prisoners. Day and night, their anguished screams reverberated around him. In lockdown for 23 hours every day, there was no relief from the noise.

Alone in his cell, Burgos says he began a conversation with God. “This can’t be it,” he said. “You have to have more for me.”

Two weeks later, Burgos received a letter. It was from Michigan attorney Deborah LaBelle, who was advocating for juvenile offenders who’d been given mandatory life sentences. At the time, Michigan had the second-highest number of juvenile lifers in the country. Burgos was one of them, sentenced to life without parole when he was just 16 years old for shooting twin brothers in a drug deal gone wrong. One of the brothers had died; the other was left a paraplegic.

When she contacted Burgos, LaBelle was just beginning her work, collecting information and raising awareness. Eventually, she would sue the State of Michigan to abolish life sentences for juveniles. But at the time, she was just getting started, hoping Burgos would be willing to take a survey and be part of her efforts.

This, Burgos says, was when he found hope—and his most joyful moment. “It was a long tunnel, but I finally saw some light,” he says.

Burgos found a typewriter and began doing what he could to aid LaBelle’s work. “I was writing letters to everyone I could think of, and sending petitions out.” In prison, he says he found a new community of people who had come to prison as kids, just like him.

“It felt good to get back in the fight,” he says.

In 2012, the Supreme Court ruled in Miller v. Alabama that a mandatory life without parole sentence required by a statute for juveniles constituted cruel and unusual punishment. In 2016, in Montgomery v. Louisiana, the Supreme Court decided that the Miller v. Alabama ruling applied retroactively to those currently serving out sentences. In other words, prisoners like Burgos.

Jose Burgos in Detroit, July 2020. Photo by Lon Horwedel.

At Burgos’s resentencing hearing in May 2018, the judge praised Burgos’s growth in prison. He’d earned his GED. He’d mentored at-risk prisoners and trained assistance dogs. He acknowledged his victims and said he’d never stop trying to repair the damage he’d done.

Ayman Kaji, the victim of Burgos’s crime, was in support of his release. “If Mr. Burgos can do good out in society, I’m all for it,” he told the court.

Sharing Stories of Incarceration

Burgos’s story of incarceration was documented by the Confronting Conditions of Confinement research team at the University of Michigan. They interviewed Burgos in February 2020 to record his story as part of an effort to document the various conditions, impacts, and costs of being confined in a Michigan correctional facility.

Now, a new collaboration between the Confronting Conditions of Confinement team and the Bentley Historical Library means that stories like Burgos’s may eventually be archived for researchers in the future.

“It’s our hope and goal that the Bentley will be a steward of the oral histories and written correspondence we collect,” says Nora Krinitsky, director of the Carceral State Project at U-M, which oversees the Confronting Conditions of Confinement team as part of a larger research initiative called Documenting Criminalization and Confinement (DCC).

Krinitsky says that being in communication with the Bentley from the project’s early stages helped them know what information to collect—and how.

“Archivists at Bentley have helped us understand how to track metadata, how to digitize materials, and how to keep track of everything we’re collecting,” Krinitsky says.

So far, Krinitsky says that more than 150 people have agreed to participate in the Confronting Conditions of Confinement project, providing details about their contact with the criminal legal system before prison, the living conditions in the correctional facilities where they are incarcerated, what community is like in prison, what their incarceration means to them, and more. As the COVID-19 pandemic has threatened many prison populations, collected stories have included accounts of illness and quarantine as well.

Full of Silences

“If you go to Bentley right now and want to learn about prisons, the best collections are the governors’ papers, but it’s almost exclusively the State’s perspective that’s represented,” says U-M Professor Matthew Lassiter.

Lassiter is a primary investigator on the research grant funding the DCC work, along with U-M Associate Professor Ashley Lucas (see sidebar).

“Archives have always been full of silences, and they privilege certain voices,” continues Lassiter. “In the case of prisons, you’re getting the perspective of the State actors who are controlling the lives and the conditions of the people who are incarcerated, but almost never the experience of the incarcerated people themselves. Most of those voices are excluded from traditional archives.

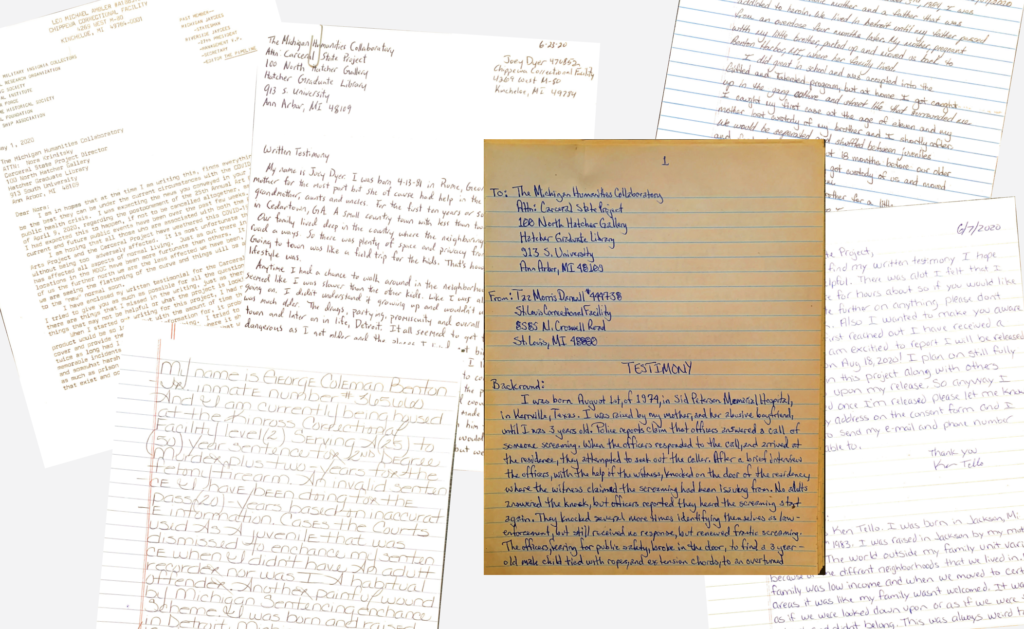

Letters like these from incarcerated individuals will be archived at the Bentley in the future.

“That’s because, for a long time, archives have prioritized the powerful. That’s been changing, but we feel like incarcerated people are one of the last groups that is beginning to be a priority for archives.”

Lassiter says that he was inspired to collaborate with the Bentley on the Carceral State project after bringing cohorts of undergraduates to the archive for more than six years to investigate topics such as environmental activism, Michigan’s anti-Apartheid and anti-Vietnam movements, and policing in Detroit. Each cohort of students then developed an online public exhibit about their research.

“This gave me the idea of working with the Bentley and donating materials from my environmental and police history projects. It’s essentially a process of using the Bentley’s resources to develop research questions from the archives, and especially to identify historical actors that my student research teams can interview, then donating these oral interviews to the Bentley. This will expand Bentley collections and bring the voices of even more political activists into the archives.”

Bentley archivist Michelle McClellan has been collaborating with Lassiter and Krinitsky to help make the eventual transition of these materials possible.

“The history of incarceration is part of Michigan history,” McClellan says, “and not something to keep separate as an uncomfortable side note. The history of the carceral state intersects with racial justice, gender and the family, economic and political history, education, and more. We at the Bentley are stewards of Michigan’s past. Our role is not just to celebrate the good but to bear witness to difficult histories as well.”

For his part, Burgos says he hopes that sharing his story will help future generations of researchers. “Maybe it can inspire kids who will go to school years from now, who are pursuing careers in criminal justice. It’s important that this process, and the people, are all humanized.”

Leaving a Legacy

On a sunny day in July, Burgos walks along the Detroit Riverwalk, near the River Front Café. He’s almost off parole, excited to have that part of his incarceration behind him.

He talks about his job at the State Appellate Defender’s Office helping prisoners prepare for release in a program called Project Re-Entry. “People were out here fighting for me, and now I can guide guys in the same way,” he says. “I want to give someone that same feeling.”

It may be years before Burgos’s story makes its way to the Bentley. Krinitsky, Lassiter, and their collaborators across U-M and local communities are just getting started, and the COVID-19 pandemic has made accessing individuals’ stories more difficult.

Even once the materials are compiled and handed over, Bentley processors will need to go through them to catalog everything. Descriptions will be written. Digital materials will be hosted online. Finding aids will be created. It’s what the Bentley does, and it all takes time and care.

This doesn’t put a dent in Burgos’s optimism. “I don’t have bad days,” he says.

He talks about the book he might write in the meantime, and how words inspire him. “In prison, I thought about books, like, those will last as long as man is on Earth.”

He pauses. “And it’s the same thing at the Bentley, I think. I hope my words there will leave a legacy, too.”