Magazine

Michigan’s “Black Bart”

by Madeleine Bradford

The new man in town was a murderer. Judge Edwin Weiser spotted him on the street and was sure of it. There was the small mustache, the large ears, the slight build. He matched the newspaper descriptions exactly.

Reimund Holzhey, the notorious thief who had killed a banker in a stagecoach holdup only a few days prior, was hungry, exhausted, and hunted. He needed a room for the night, and Republic was the nearest town. It was August 30, 1889.

Pausing their cribbage game, William O’Brien, the former detective who owned the hotel, and Albert Drake, a local sharpshooter, turned to look at the newcomer. According to Drake’s eyewitness account, Holzhey requested a room, food, and a bottle of pop.

“Have you seen that man before?” O’Brien asked, when Holzhey left.

Drake hadn’t. O’Brien went to get a newspaper clipping from his back room, examined it, and was confident he had just seen a stage robber and murderer.

“Now, don’t you open your mouth,” he told Drake, “I want you to go and look for Deputy Sheriff John Glode, and Pat Whalen, the night marshall.”

Glode and Whalen hurried over to the hotel, along with Judge Weiser. All agreed: Holzhey had to be the wanted man. They’d catch him unawares in the morning. Dressing in civilian clothes, they set out the following day.

What happened next? Well, it depends on who you listen to.

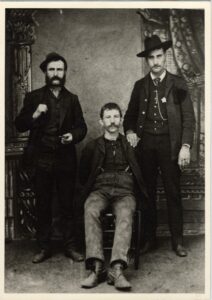

Outlaw Reimnund Holzhey (middle) along with Deputy Sheriff John Glode (right) and Pat Whalen (left).

Albert Drake claimed to have crouched on the veranda of the hotel with his gun, while Glode and Whalen ambled along the road. Splitting up, they let Holzhey walk between them. They hurled themselves at Holzhey from either side, crashing to the ground. Struggling to reach for his pocket, and the gun hidden within, Holzhey found himself overpowered by the night watchman’s club.

Different newspapers juggle the facts. In some versions, Glode and Judge Weiser caught Holzhey together, and Whalen goes unmentioned. According to Glode’s daughter, it was Glode alone who managed the capture, as Holzhey kicked Judge Weiser in the leg.

Regardless of how, Holzhey was caught. He was questioned in the town hall, and his captors sent a telegram to “Chas M. Howell,” the prosecuting attorney for the stagecoach murder.

They also hired a photographer: William Whitesides of Ironwood, whose photography practice spanned the Upper Peninsula.

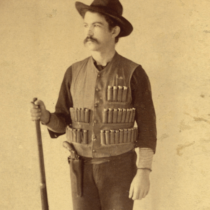

For an individual portrait, Whitesides dressed Holzhey up in a vest full of oversized cartridges, and posed him with an empty pistol and a rifle, mimicking a famous photo of Billy the Kid.

For the group photograph, these props were taken away. Whitesides brought out a painted backdrop—the kind often used for family portraits. Night watchman Whalen and Deputy Sheriff Glode changed into their uniforms, and Holzhey was then posed sitting on a chair between them, staring straight ahead. Behind them, painted curtains. Scrolling columns. Ahead of Holzhey: a trial and two life sentences. (He would serve about 25 years in the Marquette prison before being paroled for good behavior.)

But how, exactly, did these photographs of the stagecoach robber and his captors end up in the Bentley Historical Library?

The Safety Net

It starts with a man who kept an archive in his closet.

It wasn’t that Victor Lemmer set out to become a historian. Born and raised in Escanaba, Michigan, he had an economics education from Notre Dame. He stumbled, almost accidentally, into a specialty in the history of the Upper Peninsula (U.P.), as the first auditor of Gogebic County. Understanding the economy of this remote area in the southwest corner of the U.P., along the border of Wisconsin, turned out to require learning mining history.

The more he learned, the more he found he loved it.

Lemmer’s “closet archives” began in earnest in the 1930s, filling up with shards of the past: photographs gifted, letters exchanged, and newspapers collected. As so many local historians end up doing, Lemmer also became a safety net for papers otherwise destined to be mulched. Fragments of people’s lives piled up higher and higher.

It became apparent that a closet wouldn’t cut it.

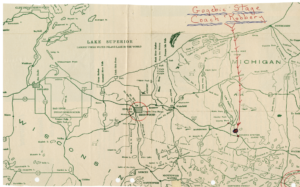

Victor Lemmer investigated Holzhey’s final stagecoach robbery for years and plotted the coach’s ill-fated route in red on this map. The robbery’s location is circled.

Lemmer’s interest in history bloomed. He joined historical societies. He began writing about his collections, presenting on telephone development, ore, gemstones—and the Gogebic stagecoach robbery.

Opening the first folder of material labeled “Holzhey’s Stage Coach Robbery” from Lemmer’s collection, it’s clear that Lemmer actively wrote to people connected with Holzhey’s arrest. There are letters from Albert Drake, and from John Glode’s daughter.

A neatly typed description of the Gogebic robbery court case, which would go on to be published in Michigan History magazine in 1954, showcases Lemmer’s investigative work. In the second folder, filled with newspaper clippings and photographs, a line of red cuts through a map of Gogebic County, showing a painstakingly plotted chart of the stagecoach’s fatal journey.

The place of the robbery is circled, pinning a dramatic chapter of Michigan’s history in place. Lemmer knew the value of detailed evidence. He was willing to put the work in to get it—from literally mapping the incident, to locating an eyewitness account.

The Eyewitness

“You got the right man, you did a good job.”

Holzhey’s words upon being arrested, according to Albert Drake, were surprisingly polite—at least until he added, “I only regret being taken in a little mossback town like this.”

Drake was around 90 years old when he wrote this description. Even if embellished or imperfect, his account still provides valuable details, about both the arrest and life in the town of Republic. With eight saloons and ungraded roads, it was “as tough a pioneer town as anywhere in the Upper Peninsula,” he wrote.

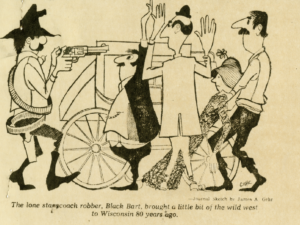

Eyewitness descriptions also help make sense of the many contradictory accounts, generated as Holzhey’s exploits blazed across newspapers in the Upper Peninsula and Wisconsin. Lemmer’s second folder of material about Holzhey bristles with clippings, showing Holzhey almost as a storybook cowboy villain.

Other newspapers depict a life that was much rougher, and less romanticized. Escaping from Germany to avoid being drafted into the army, Holzhey claimed to have suffered from mental illness from childhood. He had periods of hazy memory, and violent impulses that he said he was unable to control. His defense pleaded insanity.

It was an explanation the jury simply didn’t buy.

The Trial

To the general public, Holzhey was an “outlaw,” a “lone highwayman,” a “desperado”; to pursuers, he was the “cleverest woodsman in the Northwest.” Called the “Black Bart of Michigan” and the “Jesse James of Wisconsin,” Holzhey had a reputation that left little doubt that he would be convicted. He held up entire trains on his own, robbed coaches and individuals, and the fear of him kept people from traveling in the Upper Peninsula.

Newspaper headlines and stories capture the fascination with Holzhey’s crimes and capture, including a cartoon depicting him as a storybook cowboy villain. Holzhey was responsible for at least one death.

“Donate. I’m collecting,” was his demand to the stagecoach traveling down to Lake Gogebic on August 26, 1889, according to newspaper clippings. In a pretense of obedience, one passenger, Donald Macarcher, reached into a pocket—and pulled out his own gun. Holzhey began to shoot, hitting both Macarcher, and Adolph G. Fleischbein, a mustachioed banker who also fired back. The stagecoach sped away, but Fleischbein fell, landing in the dirt. He begged Holzhey to spare him.

Holzhey did.

He left after robbing Fleischbein. By the time help came for Fleischbein, however, he had been bleeding for too long. Nothing more could be done.

Holzhey took just four things, according to Lemmer’s transcription of the Gogebic Court record: a gold watch, a pocketbook, a 10-dollar gold coin, and a five-dollar bill.

Ultimately, that’s what betrayed him. Discovering Fleischbein’s valuables on Holzhey upon his arrest, the officers knew they’d found the right man. Holzhey later bitterly recalled the trial in a letter published by the Detroit News:

“Do you know what these [ . . . ] men will do with a human brother whose maddened brain drives him hither and thither like a dry leaf in a storm wind? If they can in any way do it they will take him alive and put him through what they call a fair trial, then they talk about god and the law, when in fact it is but a matter of friends and gold . . .”

It was a matter of gold—both the gold Holzhey stole, and the gold of the reward money for his capture, which was reported to reach $3,000 (an astronomical sum at the time). There was also overwhelming evidence that Holzhey had committed the crimes he was accused of: his admissions, his identification by others who rode the stagecoach, and the goods from various robberies were enough to keep him locked up.

What Happened Next

John Glode allegedly kept Holzhey’s spiked shoes for years, along with his red handkerchief, which he used to cover his face in early robberies. Glode’s daughter, Lucille Austerman, wrote about them to Lemmer, as part of a description of her father’s life. Eventually, Glode’s wife decided enough was enough and discarded the objects, according to Austerman, but she still claimed to have “the large gun Mr. Holzhey used.”

Meanwhile, Holzhey himself did not take kindly to prison.

After violent outbursts, including one where he took a prisoner hostage, and several attempts to starve himself, Reimund Holzhey was sent to the Michigan Asylum in Ionia.

Exactly what operation he underwent there remains unclear, but by all accounts he came back a changed man. One newspaper reports that a bone that had been “pressing on his brain” was lifted; another says a “metal plate” was inserted into his skull. Whatever the case, Holzhey became a model prisoner, started writing a newsletter for the prison, took charge of the prison library, and even became the mugshot photographer.

His urgent petitions for release were granted in 1910; on his first night as a free man, he reportedly stayed awake, outside, staring at Ives Lake, and waiting for the sun to rise.

Changing his name to Carl Paul, Holzhey ended up working as a photographer and writer in Sanibel, Florida. There, he would eventually take his own life, leaving behind only a note with his date and place of birth written on it.

Victor Lemmer himself eventually found places to store his archives outside of his closet. The Archives of Michigan and the Bentley Historical Library both received wonderful troves of Upper Peninsula history from Lemmer’s collections. You can come to the Bentley Historical Library to look through his 10-box collection, where you can read about everything from gold mining to ghost mines—or even hold the actual photographs of Reimund Holzhey himself.