Magazine

Black and Blue

by Robert Havey

When Gerald R. Ford ran for president in 1976, he answered critics of his civil rights record by telling a story from his college football days at Michigan.

His good friend and teammate Willis Ward was told he couldn’t play in U-M’s game against Georgia Tech. In 1934, schools in the Jim Crow South refused to compete against Black players, even for road games. Ford said he and the rest of the team threatened to not play until Ward convinced them they should.

When Ford wrote an op-ed in the New York Times in 1999 defending U-M’s affirmative action policy, he said Ward had “decided on his own not to play,” and “[h]is sacrifice led me to question how educational administrators could capitulate to raw prejudice.”

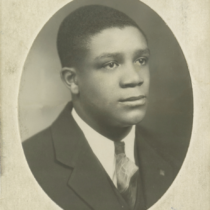

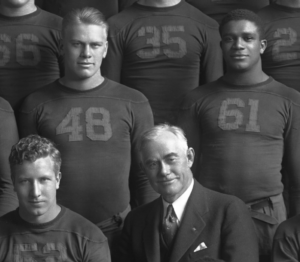

Clockwise from top left: Gerald Ford, Willis Ward, Fielding Yost, and team captain Tom Austin from the 1934 football team photo.

When Ford died in 2006, President George W. Bush gave a eulogy that used Ward’s story as an example of how Ford “confronted racial prejudice” and displayed “character and leadership.”

These retellings brought Ward and the Georgia Tech saga to a national audience for the first time in more than 60 years. But Ford’s version of the story should be taken with a grain of salt. Often left out in the retelling is Ward himself—how he came to be at the center of a campus crisis and how he was affected.

Digital archives at the Bentley like the Michigan Daily Digital Archive and the upcoming African American Student Project database make it possible to put together a more complete picture of what life was like at Michigan for Black athletes like Ward, before and after that infamous game.

A Rare Talent

Willis Ward’s father was not thrilled at his son’s ambition to attend college. He liked the idea of him playing football even less.

“I was the youngest of seven children of a factory worker,” Ward explained in a 1970 interview with U-M graduate (Ph.D. ’70) and Tri-State College Professor John Behee. Ward said his father believed “a man ought to grow up, marry, work hard, sit on his own property, behave himself, and get into heaven.

“He didn’t believe that one white kid would block another white kid for a Black kid to make a touchdown. The world didn’t function that way; they would gang up and do me up.”

At Detroit’s Northwestern High School, it became clear what transcendent athletic talent Ward possessed. He broke the Michigan state records in the high and low hurdles and the world scholastic record in the high jump. Twice. In 1934, he made the all-state football team.

Ward also did well in school and became one of the few Black students at Northwestern to be put on the college-track curriculum. In his interview with Behee, Ward explained that it was assumed college prep was a “waste of time” for the rest of the Black students since they “lacked the means to pay for college.”

Ward was set to enroll at either Dartmouth or Northwestern University when a group of influential U-M alumni approached him and asked if he would consider coming to Michigan. Ward was interested, but there hadn’t been a Black football player at Michigan since George Jewett in 1892. It was widely known that Fielding Yost, legendary U-M football coach and then the athletic director, strictly enforced this unwritten ban.

The alumni group eventually convinced the current football coach Harry Kipke to defy Yost and add Ward to the team.

Same Campus, Different Worlds

Both Ford and Ward arrived in Ann Arbor in the fall of 1931. They both were highly touted football recruits who dreamed of playing in the Big House. Both had to find part-time jobs to afford tuition.

But the Ann Arbor that Ward stepped into was one very different from Ford’s. Ward was Black while his professors, teammates, and nearly all of the U-M student body, weren’t. Of the 9,707 students enrolled that semester, only 61 were Black.

Housing for the few Black students was de facto segregated. There were no dormitories for men in 1931 (the first, West Quad, wouldn’t open until 1939). The only options for Black male students were boarding houses in Ann Arbor’s Old Fourth Ward or pledging an all-Black fraternity. Ward was able to join Alpha Phi Alpha and lived at the chapter house on 1183 East Huron for most of his time at U-M.

“Black kids were so poor, in the main, they couldn’t afford to go to Michigan,” said Ward in an interview with Behee. “The black students that could qualify and had the means were so few and far between. There wasn’t even enough there to pay attention to.

“It was lonely. Lonely as hell.”

Kipke got Ward a job washing dishes at a bar on State Street called The Parrot. “The cook happened to be a Black man,” Ward recalled. On hearing that he was going to play football, the cook “fed me better than he fed anyone,” Ward said. After a month, the owner took exception to Ward’s budding campus celebrity and told him to use the back entrance. The next day Kipke got Ward a job washing dishes at the Michigan Union, a highly sought-after job usually reserved for upperclassmen. Ward was the first Black student to work in the Union.

Equal Ground

It didn’t take long for Ward to earn his reputation as an elite athlete. In November 1931, The Michigan Daily wrote that the young star “proved his worth” playing “outstanding” offensive and defensive end on the freshman football squad. Ward often won all three of his events at freshman track meets. So often did Ward account for a majority of U-M’s points in the final total, the Daily dubbed him the “One-Man Track Team.”

Ward won two national championships with the varsity football team in 1932 and 1933. The game reports in The Michigan Daily are filled with his heroics: a blocked extra point in a 7–6 win over Illinois; an interception at a pivotal moment against Ohio State during homecoming; a safety followed shortly by a touchdown reception against Princeton.

Ward executing the high jump, 1935.

While one side of the sports page celebrated Ward’s football prowess, the other prayed he would stay healthy for track season. In October 1932, a Michigan Daily columnist beseeched varsity track coach Charles Hoyt to stop Ward from playing football, since “if something should happen to Ward . . . Michigan would be a greater loser in track than his admittedly good football ability would gain.”

Gentleman’s Agreement

Fielding Yost scheduled the football game against Georgia Tech for October 20, 1934. There wasn’t a plan in place for what Michigan would do about Ward and Georgia Tech’s refusal to compete against a Black player. It’s unclear if Yost ever had an idea how it would play out, but it is certain he knew it was an issue long before game day. Yost knew Georgia Tech’s coach personally and received many increasingly frantic telegrams from him asking for his assurance Ward wouldn’t play.

Word got out about the situation and quickly spread all over campus. The first letter to the editor appeared in the Daily on October 9, 1934: “This is a very cosmopolitan campus, where racial discrimination is supposedly abolished. But is it?” The front page of the October 10 issue included a statement from the Ann Arbor Ministerial Association condemning Ward’s benching.

A person going by just the initials L.E.T. wrote to the Daily asking those defending Ward to “inject a little tolerance into your stand-pat attitude,” and “remember that antipathies thrive on just such an unbending attitude.”

The next day, apparently satisfied with presenting the two sides of the issue, the editorial board declared: “The subject has been covered, as fairly and as impartially as possible, from all angles.” (It hadn’t.) “The Daily will not publish any more letters on this subject.” (They did.)

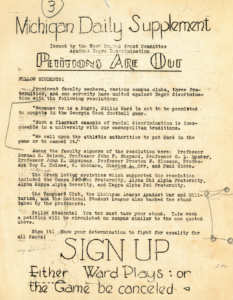

A Michigan Daily

petition announcement

supporting

Ward being permitted

to play against

Georgia Tech.

On October 19, a mass meeting at the Natural Science auditorium was called by the “Ward United Front Committee” to present their case to the student body. Almost immediately the meeting devolved into heckling and shouting as a “Tory student group” (likely Michigamua, a senior honor society that became known for its initiations that appropriated Native American imagery) sought to sabotage the meeting in any way possible. Coins were thrown at the speakers. A few people in favor of Ward sitting out said it was actually out of concern for his own well-being. Others presented the forced removal of a player because of their ethnicity to be a matter of “tact” and “hospitality.”

One of these counter speakers later admitted that their strategy was to “break up” the meeting by “making filibuster speeches.” They added, “It got pretty funny before it was over.”

The Trouble

Ward didn’t play in the game against Georgia Tech. Many accounts have it as Ward’s decision, but it is hard to see what his other choices were. He talked to coach Kipke, his first ally on campus, and confided in him that this made him want to quit.

Ward remembered Kipke telling him, “But for the problems that a coach goes through playing a Black athlete today, if you quit now, it’s not worth the struggle. And I won’t play a Black athlete again.”

Suddenly, Ward wasn’t just responsible for being the best student athlete he could be. He was on the hook for every future Black athlete with dreams of playing for Michigan. The fallout of that moment for Ward was devastating. His grades fell. He began to feel the pain of all the slights he had ignored over the years, including never being voted football or track captain.

“All of a sudden now, the practice that you did because it was the thing to do to be good . . . all of a sudden becomes a work of drudgery.”

The Last Leg

Despite everything, Ward still gave his all in his last track season. Possibly his most enduring athletic feat was when he beat Ohio State’s Jesse Owens in the 60- and 100-yard dash.

It was bad enough to have Jim Crow seek him out in Michigan. He didn’t need to travel abroad to be subjected to the same discrimination. So, disillusioned and heartbroken, Ward chose to not participate in the 1936 Olympic Games in Berlin. He hung up both his track spikes and football cleats for good.

Even if Ward wanted to try professional football, there were no Black players on any NFL teams in 1934. Yet another unwritten rule kept all Black players off NFL teams until after World War II.

Ward was offered a job at the Ford Motor Company after graduation. The position was an important but delicate one: Ward was the assistant to Donald Marshall, the head of the Negro Division of the Service Department. His job, as he saw it, was to fight for the Black workers and ameliorate racial conflict, all while distancing himself from the brutal union-busting that Ford had become known for. Ward left Ford to enlist in the U.S. Army during World War II. His replacement was his onetime greatest rival: Jesse Owens.

Ford obtained his law degree from the Detroit College of Law in 1939. He worked his way from Wayne County Prosecutor to Assistant U.S. Attorney for the Eastern District of Michigan to the head of the District’s Civil Division.

Ward was appointed by Governor George Romney to the Michigan Public Service Commission in 1966. Ward was the first Black commissioner in the state agency in charge of all public utilities. His appointment came after an enthusiastic recommendation from his onetime teammate, Congressman Gerald Ford.

Despite everything, Ward stayed committed to the University of Michigan, even doing some recruiting for U-M football coach Bump Elliott.

“I’ll do everything in the world to get you some fine Black athletes,” Ward recalled saying to Elliott. “Bear in mind I know the story. I just don’t want that kid to ever look me in the face and say, ‘You sent me to a school where they are prejudiced against me because of my color.’”