Magazine

The Great Debate

by Robert Havey

What is the universe? How big is it? What is our place in it?

Astronomers have been trying to answer these questions for centuries, from Aristotle to Ptolemy to Copernicus. By the 1800s, advances in telescope technology and scientific techniques led to a consensus that the Earth orbited a sun, and that our solar system was part of a band of stars known as the Milky Way. If you asked a 19th-century astronomer, they would say the sun is at the center of the universe, which measures just 30,000 light years across.

In 1908, Harvard astronomer Henrietta Leavitt discovered a technique that allowed for a much more accurate measurement of the distance of stars from Earth. Using a variable pulsating star, a special type of star that changes its brightness at a regular interval, as well as trigonometry, astronomers discovered that galaxies they thought were “close neighbors” were in fact very, very far away. Suddenly the universe was too big to fit into our idea of it.

Enter the debaters: astronomers Harlow Shapley and Heber Doust Curtis. By 1920, both men had published papers arguing their perspective on what the new “model” of the universe should be. The National Academy of Sciences invited them to present their findings at a formal event on April 26, 1920 at the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C.

Shapley, an astronomer at the Mount Wilson Observatory, presented first. While being a chance for the young scientist to make his mark, it was also a job interview of sorts. Shapley was a candidate for director at the Harvard College Observatory and his potential future colleagues were in attendance.

The North American Nebula, photographed with the Heber D. Curtis Schmidt Telescope at the Portage Lake Observatory, in 1951.

Shapley used Leavitt’s technique to find the distance of groups of stars called “globular clusters” and with that data, make a better map of the Milky Way. His conclusion was that the Milky Way, and therefore the universe, was 100,000 light years across, 10 times larger than the previous best estimate. Also, since more of the clusters appeared in one part of the sky, our solar system was not in the center of this new map.

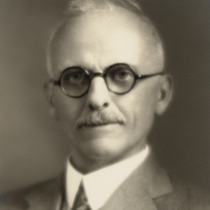

Next up was Curtis, the director of the Lick Observatory and future director of U-M’s Detroit Observatory. Unlike Shapley, Curtis didn’t just read his paper, but presented it, rarely looking at his written notes.

Curtis had used the light of new stars (nova) in the Andromeda Nebulae to estimate their distance from Earth to be an incredible 500,000 light years. Because that distance is so much larger than all other estimates of the size of the Milky Way, Curtis argued that observed galaxies weren’t part of the Milky Way at all and instead were separate galaxies all their own. The universe comprised many “island universes” like Andromeda and the Milky Way.

Curtis argued that because there were so many of these “island universes,” they couldn’t be as large as Shapley estimated the Milky Way to be. He maintained that the sizes for Andromeda, the Milky Way, and other galaxies were all probably about 30,000 light years in diameter.

So who won? After the debate Curtis wrote to his family: “Debate went off fine in Washington, and I have been assured that I came out considerably in front.” In his memoir, Shapley wrote “Curtis was right partly, and I was right partly,” although he admitted, “Curtis did a moderately good job.”

We now know that both men were about half right. Shapley’s map of the Milky Way was much more accurate: the actual size is around 105,700 light years across, and our solar system is not at its center. Curtis’s contention that there are many different “island universes,” not just our Milky Way, turned out to be correct also, although he still underestimated the sizes of those universes.

Much like past attempts to answer the big questions of astronomy, the Shapley-Curtis debate didn’t solve the mystery, but it did provide better, less wrong answers to improve upon.

If you asked an astronomer today, most would say the size of the (observable) universe is about 93 billion light years and our sun is one of the 400 billion stars in the Milky Way, which is one of the two trillion galaxies. Enough is still unknown that another Great Debate could be held today, maybe on “What is Dark Matter?” or “Are there multiple universes?”

Heber Curtis’s papers, including his 1920 speech titled “Island Universes,” are open to researchers at the Bentley Historical Library.