Magazine

Flying Saucers and Swamp Gas

A rash of UFO sightings across Michigan in the mid-1960s launched investigations by the highest levels of the U.S. government. What was happening in the skies? Collections at the Bentley document several aspects of these widespread close encounters. Was it spaceships or swamp gas? The answer may depend on whose papers you peruse.

by Lara Zielin

Frank Mannor was spending a quiet night at home with his wife and teenaged son, Ronald, on the evening of March 20, 1966. All was peaceful at their farmhouse just northwest of Dexter, Michi-gan—until around 8:30 p.m. That’s when they saw the lights. Something unusual was in the sky outside their farmhouse.

They watched from their windows as a strange object appeared to land on their property. Then Frank and Ronald dashed from the house to investigate.

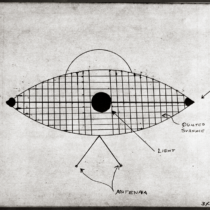

The object hovered above a nearby marshy area, pulsating red and green lights. Frank and Ronald described it as large, brown, and sphere-shaped, with a “quilted” pattern on its surface.

At one point the object’s lights went out and it disappeared, only to reappear seconds later, about 500 yards away. Then they heard a sharp sound, “like a rifle bullet ricocheting off an object.” The strange craft lifted into the air, paused directly above them, and disappeared.

The Mannors phoned law enforcement to explain what they’d witnessed. Instead of being laughed at, their report was taken seriously. Police officers on patrol that evening had seen something similar. Washtenaw County Sheriff’s Cpl. David Severance even drew a picture of it based on witnesses’ descriptions.

What’s more, sightings had been happening all week. The previous Monday, police on patrol in Lima Township, southwest of Dexter, had witnessed four lights flying with great speed and “amazing maneuverability” in the early morning hours. One officer even attempted to take photos.

Officer David Severance’s drawing of a UFO above Dexter Township in 1966, as described by witnesses.

The day after the incident at the Mannor farm, lights were reported about 60 miles southwest of Dexter at Hillsdale College. In this case, several undergraduate women saw lights outside their dorm windows. They phoned William Van Horn, the Hillsdale County Civil Defense Director, who arrived with a patrol car and also saw the lights firsthand.

The incidents were so widespread and witnesses were so credible that senators, governors, law enforcement, and researchers would become involved, trying to understand what was happening. Today, numerous collections at the Bentley document much of this activity—from archived newspapers to governors’ papers to faculty correspondence and more.

What happened in spring 1966 in Michigan? It may be impossible to know, but a dive into archived materials certainly reveals what happened next.

“These People Have Seen Something”

Washtenaw County Sheriff Douglas J. Harvey knew the Mannors and had visited them on the night of March 20. He found their testimony to be credible and took their account seriously. “These people have seen something,” Harvey said, refuting rumors that the family was seeking publicity or was somehow deranged.

Harvey’s officers were among those who had also witnessed the unexplained lights. “I know my men and I trust their reports,” Harvey told the Ann Arbor News on March 22. “I don’t know what it is, but I’m sure they have seen something aloft.”

Harvey asked for help investigating the incidents from several federal agencies but was repeatedly ignored. Desperate, he reached out to Weston Vivian, his congressional representative.

Vivian took Harvey’s request seriously. This may have been motivated, in part, by his constituents’ concerns about UFOs. A file in his collection contains letters from citizens pre-dating the 1966 incident, asking for information and relaying worries about UFOs. (More public letters conveying UFO concerns and predating the 1966 incident can be found in the collections of other politicians, including Michigan Senator Phil Hart and Representative William D. Ford from Michigan’s 15th district.)

Vivian pulled enough strings to get the U.S. Air Force to send out an investigator—J. Allen Hynek, Ph.D., an astrophysicist from Northwestern University.

But soon Hynek’s presence would create more problems than it would solve.

Into the Field

Hynek was a respected academic who had worked at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory during World War II, then as a full professor in physics and astronomy at Ohio State University. He eventually left Ohio State to conduct research at the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory, where he worked on a U.S. satellite program in the late 1950s. When the program ended, he returned to teaching at Northwestern University, where he chaired the astronomy department.

He did all this while consulting on the side for the United States Air Force about UFOs.

Beginning in the late 1940s, Hynek was asked to advise the military on Project Sign, an investigation into a rash of reports about strange objects in the sky. Project Sign eventually morphed into Project Blue Book in 1952.

Hynek initially approached the UFO reports with a great deal of skepticism. After all, they were reports. Hynek was largely behind a desk, reading accounts from people he hadn’t met and from places he’d never been.

Things began to change when Hynek went into the field, visiting with people making the claims and hearing them firsthand.

“The witnesses I interviewed could have been lying, could have been insane, or could have been hallucinating collectively—but I do not think so,” he wrote in The Hynek UFO Report: The Authoritative Account of the Project Blue Book Coverup (MUFON, 1977).

Hynek would go on to write exhaustively about UFOs, even creating a classification system for alien encounters (close encounters of the first, second, and third kind). But when he arrived in Washtenaw County on March 23, 1966, he couldn’t see much evidence that anything was awry. In fact, he devised a tidy explanation for all of it.

Nothing to See Here

On March 25, 1966, Hynek gave a press conference where he said that the incidents at the Mannor farm and Hillsdale College were the result of rotting vegetation in lowland areas. The vegetation created gasses that were trapped in winter. During the spring thaw, the gases were released. This so-called “swamp gas” phenomenon could cause lights and even sound. Hynek called it “highly localized.”

“A dismal swamp is a most unlikely place for a visit from outer space,” Hynek said at the press conference.

Furthermore, Hynek asserted that the strange photos taken by a police officer were nothing more than “trails made as a result of a camera time exposure of the rising crescent moon…and the planet Venus.”

Cartoon sent to Arthur Gallagher, editor of the Ann Arbor News, by a reader after the rash of local UFO sightings in 1966.

The public wasn’t buying it. Among the skeptics were Sheriff Harvey, who continued to support his patrol officers and the Mannors. “With all due respect to Dr. Hynek, I’m not ready to accept this weak excuse of gas from marshes,” he told reporters.

Hynek’s explanations were so unsatisfying to the public that pressure mounted for a deeper investigation.

Congressman Vivian continued to put pressure on the Air Force for more investigative resources. And he wasn’t alone. Representative Gerald Ford from Michigan also became involved, requesting a full congressional inquiry about the UFO reports.

The Air Force caved under pressure. On April 6, 1966, they announced that they would convene a group of “scientific observers to further delve into recent sightings.”

By the fall of 1966, the U.S. Air Force had commissioned the University of Colorado and physicist Edward Condon to head up a two-year project to study UFOs and to determine if the government should continue funding UFO investigations.

Known as the “Condon Committee,” this group of 11 scientists—give or take some part-time consultants— released a report in 1969 that was more than 1,000 pages long and concluded that there was nothing of scientific value in any of the documented UFO phenomena.

The report dismissed hundreds of eyewitnesses across the country—including those from Washtenaw County who saw something strange in the sky in March of 1966. The report supported all of Hynek’s findings. The Mannors were dismissed as having been too far away to know what they saw. The Hillsdale College students likely saw “young men [who] played pranks with flares.” The photos by the police officer were just what Hynek said they were—streaks of light from Venus and the moon.

In its conclusions, the report fails to validate any of the hundreds of eyewitnesses featured in its thousand-plus pages: “In our experience those who report UFOs are often very articulate, but not necessarily reliable,” the report says.

Reporting on the Reports

The Condon Report was scrutinized by members from the National Academy of Sciences to ensure its accuracy. Among the reviewers was H. Richard Crane, a distinguished professor of physics from the University of Michigan.

Crane and his colleagues concluded that the Condon Report got it right—that UFOs weren’t worth more scientific investigation, and most of what people were seeing was highly explainable.

But tucked into Crane’s archived papers at the Bentley are letters from Condon, on which Crane is copied, which speak to one of the more controversial aspects of the report: a memo by Condon Committee member Robert J. Low, an assistant dean at the University of Colorado.

Low’s memo, dated in 1966, assured University of Colorado administrators that they could expect the study to find that UFO observations have no basis in reality. The memo raised doubts about the project’s objectivity, and copies of the memo were leaked to the press. Look magazine ran a highly publicized article about it.

Controversy or no, the Air Force acquiesced to the report’s findings, and Project Blue Book was shut down in 1969.

One Grain of Red Sand

UFO sightings continue to this day, and in June 2021, an unclassified report was released to Congress about Unidentified Aerial Phenomena (AEP)—a.k.a. UFOs. The report confirms sightings by credible military personnel of objects that behave in ways that defy explanation and “may require additional scientific knowledge.”

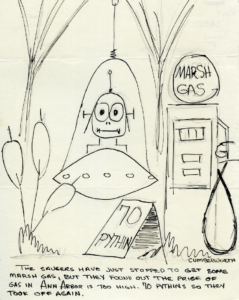

A letter in the file of U.S. Representative William D. Ford from 14-year-old Gregory Gulyas, requesting a five-year investigation into UFOs.

Once again, the door is open for further investigation.

In the archived collection of U.S. Representative William D. Ford is a 1965 letter from 14-year-old Gregory Gulyas who says he thinks “75 percent of UFO sightings are from other planets, most likely from Mars” and urges Ford to “try to ask the Senate to form a comittie [sic] to investigate UFOs for five years and publish their findings monthly in all major papers of the country.”

Ford’s response to Gulyas commends the boy’s curiosity. “You are to be complimented on having a young inquisitive mind,” he writes. “Your belief that life exists on another planet…is supported by the fact that there are numerous solar systems like our own.

“Is Earth as unique as one grain of red sand in a white sandy beach?”