News Stories

African American Scholarships During the Great Depression

by Margaret A. Leary

Early in my work on the Bentley’s African American Student Project, I was surprised to learn that the number of African American students enrolled at U-M greatly increased during the 1930s.

The Depression was an unlikely time for that. I asked and was told it must have been the scholarships that southern states gave African American graduate students to come north to study.

Crystal R. Sanders, an associate professor of African American studies at Emory University calls these scholarships “segregation scholarships,” but I had never heard of them before.

How had they come about? And what had they meant for U-M students?

Short answer: In 1954, the Brown v. Board of Education U.S. Supreme Court case erased the legality of segregated public education at any level, obliterating the “separate but equal” principle of Plessy v. Ferguson (1896). But well before Brown, the U.S. Supreme Court had determined that segregated graduate and professional education was unconstitutional: first in Gaines v. Canada (1938) and later Sweatt v. Painter (1950). These cases were essential to build the NAACP’s successful legal strategy in Brown: to use sociological evidence to prove that, in education, “separate” can never be “equal.”

Perhaps because southern states did not want to integrate their white institutions, or pay to create African American graduate universities, they chose to offer African Americans scholarships to earn graduate degrees at out-of-state (northern) schools. Each state provided varying amounts of money, administrative methods, and records. Each state began, and ended, scholarships at a different time. Identifying individual recipients at Michigan is difficult because the primary records are in the granting states.

However, the African American Student Project (AASP) has gathered much information about individual students and found several examples of scholarship recipients. Two were Theodore Calhoun from Texas, and Elizabeth Marshall Porter of Georgia. (Of note: the scholarships continued even after they became illegal.)

Theodore Calhoun, from Austin, Texas, came to U-M with a B.S. (1929) from Bishop College in Marshall, Texas. He attended summer school in 1937, 1938, 1942, 1945, 1946, and 1950, earning an M.A. in 1941. He roomed in houses in the then-African American area of Ann Arbor. His file at the Bentley includes his application for a scholarship to do graduate work in Texas in the summer of 1940.

The AASP database identifies family members who came to U-M, including two of Calhoun’s: his wife, Thelma Clarissa Calhoun, and brother Jason Norwood Calhoun. Thelma, a member of Delta Sigma Theta, had a 1934 B.A. from Prairie View State and registered in the summers of 1942 and 1950, earning no degree. Jason’s B.A. was from Samuel Houston College, where he joined Omega Psi Phi. At U-M he earned an M.S. in Public Health, in the summer 1947. We do not know whether these two family members received scholarships.

Elizabeth Marshall grew up in Columbus, Georgia, and graduated from Dunbar High in Washington, D.C., in 1929. She earned a B.S. at Fort Valley State College in 1946 and spent the next five summers at U-M, earning an A.M. in education in 1951, joining other African American students living on Woodlawn Avenue each summer. A member of Alpha Kappa Alpha, she taught in various schools in Georgia’s Muscogee County for 41 years, and lived to be 101. The Bentley holds copies of her scholarship applications to the University System of Georgia.

The AASP database shows that during the period of these scholarships (1929-1959), 1,808 individual students from southern states registered collectively 5,759 times, with 4,537 (78%) of those registrations coming when scholarships were provided. The most students came from North Carolina, Texas, and Alabama.

There is certainly more work to be done here. To further assess the scholarships’ impact, we will further explore Bentley records and other sources to identify more recipients, and then learn more about the scholarships’ impact on their lives and home states.

The African American Student Project was officially launched in 2016 in anticipation of the University of Michigan’s bicentennial. For more on the project’s research methodologies, please see Resources and Research.

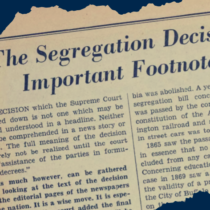

Lead image: Archived Michigan Daily coverage from May 1954 about the Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court decision.

RESEARCH RESOURCES INCLUDE:

- Endersley, James W. and William T. Horner. Lloyd Gaines and the Fight to End Segregation. Columbia, University of Missouri Press, 2016.

- Johnson, Kimberley. Reforming Jim Crow: Southern Politics and State in the Age Before Brown. Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2010. Chapter 6, “Higher Education for Blacks in the South: Pragmatism and Principle?”, p. 144-168, covers the scholarships.

- LaVergne, Gary M. Before Brown: Heman Marion Sweatt, Thurgood Marshall, and the Long Road to Justice. Austin, University of Texas Press, 2019.

- Sanders, Crystal R. You Tube presentation about her upcoming book America’s Forgotten Migration: Black Southerners and Graduate Education During the Era of Legal Segregation. About 80 minutes long.

- Sanders, Crystal R. “Biden has a unique opportunity to undo years of education inequality: the benefit of expanding funding for historically Black colleges and universities” The Washington Post Feb. 8, 2021.

- Tushnet, Mark V. The NAACP’s Legal Strategy against Segregated Education, 1925-1950. Chapel Hill, University of North Carolina Press, 1987.