Magazine

Baseball’s Barrier Breaker

Before Jackie Robinson, there was Moses Fleetwood Walker, who would use the racism and discrimination he faced in baseball to fuel a career as an editor, author, and political advocate for Black rights.

By Dr. Rashid Faisal

On May 1, 1884, Moses Fleetwood Walker took to the baseball field as a catcher for the Toledo Blue Stockings. It was his inaugural game with the team, which had just joined Major League Baseball. They were playing against the Louisville Eclipse in Kentucky.

The Blue Stockings lost that day, 5–1, in part because, as one paper wrote, Walker made “three terrible throws.” The Toledo Blade wrote about the game with more nuance and cited the “gravitating circumstances” that may have rattled Walker and caused his “poor playing.”

Walker had just broken baseball’s color barrier, more than 60 years before Jackie Robinson would play for the Brooklyn Dodgers.

All while being jeered, taunted, and harassed—or worse.

“Walker is one of the most reliable men in the club, but his poor playing in a city where the color line is closely drawn as it is in Louisville should not be counted against him,” wrote the Toledo Blade.

Walker’s experiences on the field and off would propel him to become an editor, author, and political advocate for Black rights as segregation blanketed the United States.

Academics and Baseball

Walker was born on October 7, 1857, in Mount Pleasant, Ohio, to a Black American physician, Dr. Moses W. Walker, and a white mother, Caroline O’Harra. In 1860, the Walker family moved to Steubenville, Ohio, an abolitionist hub that had served as a stop on the Underground Railroad.

Walker and his brother, Weldy, attended Steubenville High School after the community passed legislation in favor of racial integration. Walker started his athletic career in 1879 as the first Black baseball player at Oberlin College. The integrated institution established intercollegiate baseball in 1881, and Walker developed a stellar reputation as a star catcher and leadoff hitter.

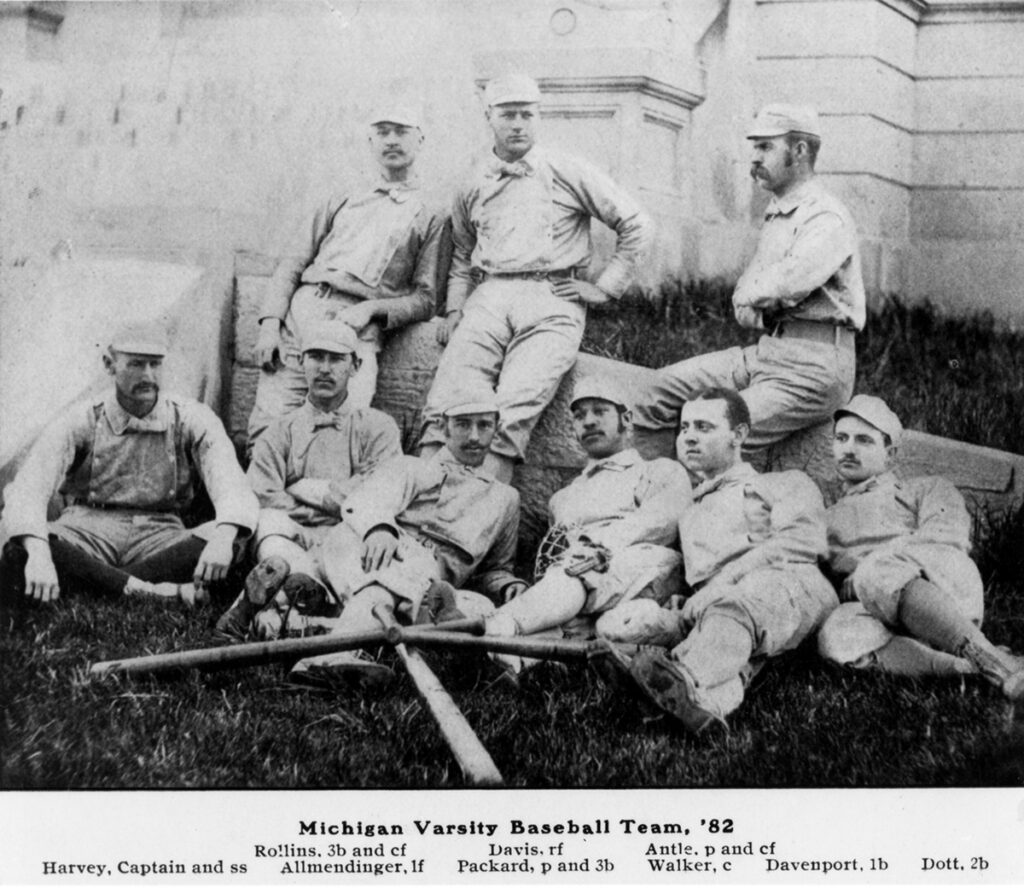

In 1882, Walker enrolled in the University of Michigan Law School. He was recruited by members of U-M’s baseball team and earned a starting position as catcher on the 1882 varsity team.

The 1882 baseball team with Moses Fleetwood Walker, front row, third from right.

Walker was the first Black American to play baseball at U-M and the first to play varsity sports at U-M. Walker helped lead the 1882 U-M baseball team to a 10–3 record and the championship of the newly formed Western Baseball League, the predecessor to the Big Ten. Walker batted .308 that season and elicited rave reviews from the Chronicle, U-M’s student newspaper: “Walker, as a catcher, did some of the finest work behind the bat that has ever been witnessed in Ann Arbor.”

In 1884, Walker left the University of Michigan to sign a semi-pro contract with the Toledo Blue Stockings of the Northwestern League. Walker would soon learn that racism awaited him at every stop during his baseball career.

“White Baseball”

Weldy Walker joined his brother on the Toledo Blue Stockings in 1884, becoming the second Black American in Major League Baseball. Weldy made his debut as an outfielder on July 15, 1884. He appeared in five games with a .222 batting average.

Both Weldy and Moses Walker experienced open racism. They were taunted and subjected to racial slurs by fans and members of the opposing team. They were spit on and threatened with lynching.

Even some of Walker’s teammates subjected him to race hate. Blue Stockings pitcher Tony Mulane admitted that Walker “was the best catcher I ever worked with. But I disliked a Negro, and whenever I had to pitch to him, I used to pitch anything I wanted without looking at his signals.”

Ahead of a game in Richmond, Virginia, the manager of the Blue Stockings, Charlie Morton, received a letter from a racist mob threatening to lynch Walker if he were to take the field. The letter read, in part: “We could mention the names of 75 determined men who have sworn to mob Walker if he comes to the ground in a suit.”

Four days later, Walker was released from the Blue Stockings.

Weldy would go on to join the Pittsburgh Keystones in the National Colored Base Ball League, although the league would last less than a year.

Walker continued to play for integrated minor leagues teams, including joining the Syracuse Stars in 1888. There, he faced the hostilities of racist fans and lasted one season before the Stars released him.

The overt racism and death threats from fans, opposing teams, even his own teammates took a toll on both his physical and emotional health. Walker officially retired from baseball in 1891 and was the last Black American to play Major League Baseball until Jackie Robinson in 1947.

Self-Defense and Equality

After his retirement in the spring of 1891, Walker was attacked by a racist mob in Syracuse, New York. One of Walker’s assailants, a white ex-convict named Patrick Murray, hit him in the head with a rock. In retaliation, Walker stabbed Murray in the groin with a pocketknife. Murray died from his injuries a brief time later.

Walker was arrested and tried for second-degree murder. The all-white jury acquitted Walker, though his legal troubles weren’t yet over. In July 1895, while working as a mail clerk in his hometown of Steubenville, Ohio, he was charged and found guilty of mail robbery. He was sentenced to one year in prison.

After his release from prison, Walker was no longer an advocate of racial integration. He and Weldy both became advocates of Black nationalism. Walker believed racial integration between the races was impossible due to white America’s unwillingness to accept and treat Black Americans as equals.

Walker and Weldy abandoned the Republican Party and co-founded the Negro Protective Party. The party’s platform called for “an immediate recognition of our rights as citizens such as have been repeatedly pledged and as often violated.” The Walker brothers published The Negro Protector as its official party newsletter.

The brothers jointly edited The Equator, a newspaper that advocated for racial separation and for Black Americans to return to Africa to free themselves from segregation, discrimination, and mob violence. In 1908, Walker published a 47-page book titled Our Home Colony: A Treatise on the Past, Present, and Future of the Negro Race in America, in which he advocated racial separation and Black Americans’ emigration to Africa. He argued against the possibility of Black and white Americans coexisting on fair, just, and equal terms.

With Weldy, Walker also opened the Opera House in Cadiz. Ohio, which hosted live performances and shows. Walker also patented several inventions related to film and “nickelodeons.”

After spending his retirement years as an entrepreneur, newspaper editor, civil rights activist, and agent for the Back-to-Africa Movement, Walker died on May 11, 1924, in Cleveland, Ohio—four years after the Negro National League was established. His remains were brought back to Steubenville, where he is buried in Union Cemetery.