Magazine

War is a Colossal Mistake

U-M’s ninth president opposed the United States’ war in Vietnam. His papers at the Bentley reveal how his experiences in an earlier conflict showed him firsthand the tragic loss of young people.

By Kim Clarke

Less than two years into his job leading the University of Michigan, Robben W. Fleming could no longer remain silent. The Vietnam War was tearing apart the campus. In his eyes, the United States’ involvement in Southeast Asia was consuming the national budget and fracturing society, while the government was drafting young men—often poor and dark-skinned—into combat.

Encouraged by left-leaning faculty and backed by his executive officers, President Fleming decided to speak out. He chose an anti-war teach-in, and an audience of 5,000 people squeezed into Hill Auditorium, in September 1969.

The war, he said, “is a colossal mistake”—one that was robbing the country of its young people for a questionable cause.

“Death on the battlefields of Vietnam is not a statistic,” he said, “it is a tragedy in the lives of a whole network of human beings.”

Fleming was a World War II veteran. One of his most challenging assignments as an Army lawyer had been defending two German teenagers charged with spying on U.S. troops.

When he told the Hill Auditorium audience, “The youth of a country are always the wave of the future,” he may have been thinking about 1945, a firing squad, and Heinz Petry and Josef Schöner.

U-M president Robben Fleming in June of 1969, standing in front of a crowd.

A Vicious Nazi System

First Lieutenant Robben Fleming dug in his heels. No, he told his commanding officer. This was an impossible order to follow.

It was late March 1945. The 28-year-old officer was moving through western Germany as part of the Allied Military Government of Occupied Territories, or AMGOT.

Fleming had earned a law degree just before the U.S. entry into the war and joined the National War Labor Board. Despite the opportunity for a draft deferment, he enlisted in 1943 and was sent to the European Theater. (“The young men of my generation were going into the service, and I could not in good conscience stay out,” he wrote years later.)

As Germany began collapsing and communities surrendered, Fleming and his fellow AMGOT soldiers worked to keep cities and villages functioning so that U.S. troops moving toward Berlin would not be at risk. That work involved rationing food, treating the sick, and providing a semblance of police, jails, and a court system that upheld justice and due process—democratic principles the Allies were fighting for on two fronts.

“The hearts of the cities were gone. They were grey destroyed masses,” Fleming wrote in GI Government, an unpublished memoir in his papers at the Bentley. “On the walls were mute reminders of the recent exit of the Nazis. Everywhere one saw signs reading, ‘Your greeting is “Heil Hitler”; ‘Long Live Hitler’; or ‘Stalin speaks to Germany.’”

Now, Fleming had been ordered to Ninth Army headquarters at Mönchengladbach, near Germany’s border with the Netherlands, to defend two German boys charged with espionage after they’d been found hiding near American soldiers. Conviction in a U.S. military court meant execution.

Over his objection to being handed a death penalty case (“since when did the Army listen to the preferences of lieutenants?”), Fleming was further frustrated by the “physically impossible task” of having only a half-day to meet the teens and prepare a defense.

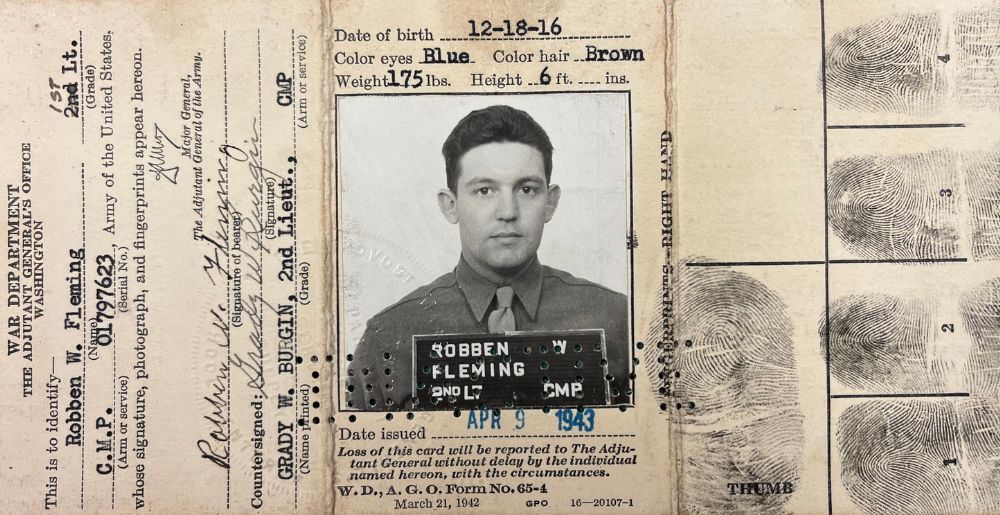

Robben Fleming’s identification card from World War II.

Heinz Petry and Josef Schöner had been arrested in late February. While Fleming never named the teens in his papers, contemporary military and news accounts identified them. He met with the boys on March 28, a day before their trial.

“One of them was a slight blond boy with nice wavy hair and a very boyish face,” he wrote. “The other was a taller, huskier, dark-haired boy—also a nice-looking kid.”

Both boys were 16 years old.

Fleming had little to work with, as Petry and Schöner had already signed confessions. But the teens had a backstory.

They told Fleming they had been conscripted into forced labor. After running away, the boys were captured and sent to a penal camp for Hitler Youth. Once there, an officer offered a way to clear their records: Sneak across enemy lines and look for U.S. artillery positions.

They were poor spies. American soldiers captured Petry and Schöner less than 24 hours after they set out on their mission. The boys said they had changed their minds almost immediately after realizing how dangerous it was.

“Both of them were, I supposed, more or less the victims of the vicious Nazi system,” Fleming wrote.

As Hitler rose to power in the 1920s and ’30s, he aimed to Nazify public education and a robust network of youth organizations that had been a hallmark of the German republic.

For children ages eight to 18, their upbringing included compulsory organizations that indoctrinated them in Nazi ideology. Parents who balked at their children’s conscription faced prison. Boys the ages of Petry and Schöner were in Hitler-Jugend, or Hitler Youth; at 18, they would move into the German Army. The Third Reich also set up Adolf Hitler Schools, which were seen as elite institutions for teaching young people leadership skills that would serve the National Socialist Party and society. Petry was sent to an Adolf Hitler School when he was 13.

Despite his sympathy for the youthfulness of Petry and Schöner, Fleming said their actions were wrong, a conviction that comes through in his archived correspondence to family members. “If they had carried out their mission and returned to the German lines as they were supposed to have, they might have caused the deaths of many of our boys.”

Fleming decided he would plead for mercy and ask the court to spare the boys’ lives because of their age, lack of actual espionage training, and the fact that German officers had coerced them. The court martial took place the next day and lasted into the evening with Fleming’s defense. With no electricity in Mönchengladbach, he argued for leniency in a room lit with candles. Court recessed at 8:30 p.m. Fleming and his young defendants awaited the verdict.

So Without Humanity

Before the panel of officers returned to the courtroom, a military aide approached Fleming. “Hand over your sidearm,” he said.

Fleming immediately knew the boys’ fate.

“If the court wanted me to remove my pistol, it could only mean that the death penalty was coming and they did not want the boys to attempt to grab my gun,” he wrote.

The president of the court read the verdict: “You will pay the supreme penalty for your offenses so that the German people will know that we intend to use whatever force is necessary to eradicate completely the blight of German militarism and the Nazi ideology from the face of the earth.”

The candles flickered as an interpreter translated the verdict. The teens were stoic. If they had been in military uniforms when arrested, they would have been held as prisoners of war. Convicted as civilians, they faced execution. The sentence was a warning to others considering spying.

Fleming silently agreed with the court. “It is a pity to have to put these kids to death,” he wrote later, “but the Nazis are utterly unscrupulous.”

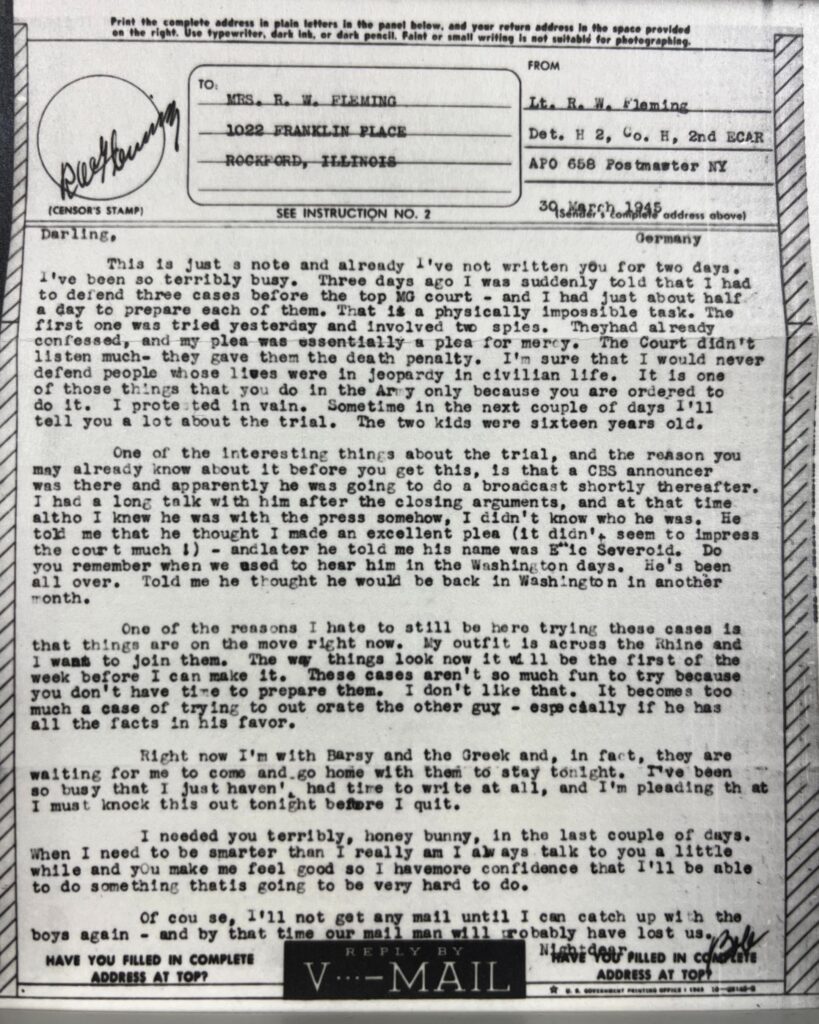

The next day, he penned a letter to Sally, his wife of three years, who was living with her parents in Rockford, Illinois, awaiting the war’s end.

Robben Fleming’s V-Mail letter to his wife after the trial.

“I needed you terribly, honey bunny, in the last couple of days,” he wrote. “When I need to be smarter than I really am, I always talk to you a little while and you make me feel good, so I have more confidence that I’ll be able to do something that is going to be very hard to do.”

Fleming visited the teens in jail to prepare an appeal. Schöner had been crying, which was the first time Fleming had seen any hint of emotion from the boys. “More than anything else, they showed an acceptance of what had befallen them.”

Using pencils, each boy wrote out an identical appeal in German. “The punishment the court of justice imposed on us is too severe,” they pleaded, “we don’t feel that our debt is that big that we should receive the death sentence.”

Fleming hoped the war would soon end and the Army would commute the boys’ sentences. The teens anxiously asked how close American and Russian troops were to capturing Berlin. “I couldn’t feel sorry for them—they would have killed us—but it all seems so useless,” Fleming wrote.

Later that night, he learned of two more German teens with cases almost identical to Petry and Schöner’s. “All of which means if the Nazis are going to play this way,” he wrote, “these kids are pretty sure to get death.”

The experience rattled him even more so as it unfolded over Easter weekend. He wrestled with the conflicting emotions of protecting American lives and the age and circumstances of the boys. He repeated details of the trial and appeal in letters to Sally, his mother Jeannette, and his younger brother Jack, an Army private stationed in Texas. He poured out his thoughts in a diary. All the materials, including the teens’ handwritten appeals, are in Fleming’s papers at the Bentley.

“I suppose that sometimes it must sound like I’m doing a lot of interesting things. In a sense I suppose I am,” he wrote after leaving the jail. “But so much of it is so empty, so boresome, so without humanity.”

Mistakes of Their Elders

Fleming never saw the boys after filing their appeal. With his unit, he moved deeper into Germany and witnessed the chaos and carnage of war: bloated corpses of horses and cows, decimated cities, looting and raping by Allied soldiers, including Americans. He was morally disgusted and physically filthy. “My hair is so dirty it is stiff,” he told his mother.

Germany surrendered on May 8, 1945, ending the war in Europe.

Rubble lining the streets of Cologne, Germany, in World War II.

On June 1, Heinz Petry and Josef Schöner left their jail cells. The commander of the Ninth Army, Lt. Gen. William H. Simpson, had rejected their appeal and upheld the death sentences. American soldiers marched the teens into a gravel quarry near Braunschweig.

Petry was first. Soldiers tied him to a wooden post as 12 military policemen assembled. Raising their rifles in unison, they shot and killed Petry. The firing squad repeated the process with Schöner. Army photographers and a cameraman recorded the deaths.

Fleming only learned of the executions a week afterward when reading Stars and Stripes. “I didn’t think they would be after the war was ended,” he told his wife. “I don’t believe they realized what serious trouble they let themselves in for.”

Fleming led the universities of Wisconsin and Michigan during one of the most turbulent eras of American history, including the civil rights movement and the Vietnam War. He was known for empathy and compassion when it came to the zeal of young people. Yet he did not tolerate civil disruption or violence.

After World War II, Vietnam, and his U-M presidency, Fleming again reflected on the spring of 1945, this time in his memoir, Tempests into Rainbows: Managing Turbulence (University of Michigan Press, 1996).

“I understood the rationale for the decision, and could accept the fact that success in their spy mission could have cost many American lives. Still, they were only sixteen years old, the war was almost over, and it seemed a pity that they had to be a last-minute casualty of the war,” he wrote. “I thought of sixteen-year-old American boys and what a tragedy it would be to have their lives cut short by the mistakes of their elders.”