Magazine

Segregated Service

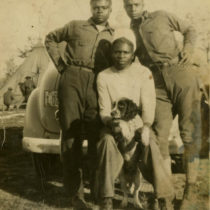

A rare set of photographs captures the working life of two African American Civilian Conservation Corps camps during the Great Depression. But who are these men and what was life in the camps like?

By Lara Zielin

Dust storms swirled on America’s Great Plains, and crops withered. Banks failed and unemployment rates soared. By 1933, 25 percent of working Americans lacked jobs, and the Great Depression in the United States was in full effect. African American men were some of the most adversely affected workers during the Depression. Discriminatory hiring was common, and demand for African American labor plummeted in the tight job

market.

To cope with massive unemployment, President Franklin Roosevelt launched New Deal initiatives in 1933, creating the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), which gave jobs to men ages 18 to 25 whose families were in need. This included African American men, whose membership was capped at 10 percent of overall CCC membership. Of the 2.5 million men who enrolled in the CCC, almost 200,000 were African American.

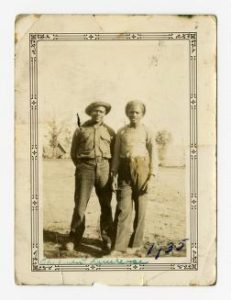

Two CCC workers stand together in a field in 1935, in the background are rows of tents and trees.

Initially, CCC camps were integrated, but by 1935, CCC Director Robert Fechner had segregated them. In Michigan, for example, out of more than 150 camps, around 14 were designated C or “Colored.”

Precious little is known about the men who served in these Michigan camps—including most of their names, or how the camp leadership, which was likely white, treated them. A recent opportunity for the Bentley Historical Library to add 30 photos from two African American CCC camps in Michigan — the Bitely and Free Soil camps — was a one-of-a-kind acquisition that helped fill in some details, but not nearly enough.

“This history has been overlooked, and I immediately understood this collection was significant,” says Mike Smith, the Johanna Meijer Magoon Principal Archivist at the Bentley, who acquired the collection on behalf of the Library.

The 30 photos include an unidentified man holding a shovel, two men standing in a field dressed for work, a portrait of a young man in his CCC uniform, and many more. Some photos have dates associated with them ranging between 1933 and 1939; others have snippets of names such as “Big Jim” and a scrawl that might read “Garfield.” But who these men are and what, specifically, their work was at camp largely remains a mystery.

“These are the only known photos of all African American CCC camps in Michigan,” says Smith, “but we need help filling in the details.”

By 1942, Congress had disbanded the CCC as men and resources left the camps to focus on World War II. But their legacy, which includes planting more than three billion trees, upgrading parks, building roads, and more, is still alive and benefiting Americans today.

Help Us Solve the Mystery

All 30 photos of Michigan’s African American CCC camps are digitized and available online at http://myumi.ch/J9NQR. Do you know anyone in these photos? Do you have any history or connection to the Bitely and Free Soil camps? If so, we’d love to hear from you.

Please contact mosmith@umich.edu with your story.