Magazine

M Glow Blue

In 1957, the University of Michigan campus sported a fully functional nuclear reactor, complete with a 55,000-gallon glowing reactor pool. Bentley collections help tell the story of why the reactor was built—and what happened to it.

By Madeleine Bradford

In 1947, the University of Michigan hatched a phoenix.

The Memorial Phoenix Project, anyway.

World War II had just ended. Facing what they hoped would be an era of peace, U-M also faced tragedy—the loss of 585 students, faculty, and staff members. With that loss came a crucial question: How do you memorialize that many lives?

According to The Michigan Daily, alumni didn’t want a “mere mound of stone, the purpose of which would soon be forgotten.”

Enter alumnus Fred J. Smith.

Everyone had seen the destructive side of nuclear research, but he thought that surely it had constructive potential, too. What about a functional memorial? What if the University used nuclear energy to help, rather than harm?

The idea sparked one of the U-M’s first major fundraising campaigns. Millions of dollars of donations later, including a large grant from the Ford Motor Co., the idea became a reality. U-M had created a project devoted to peaceful uses of nuclear energy, rising from the ashes of war.

They called it the Memorial Phoenix Project.

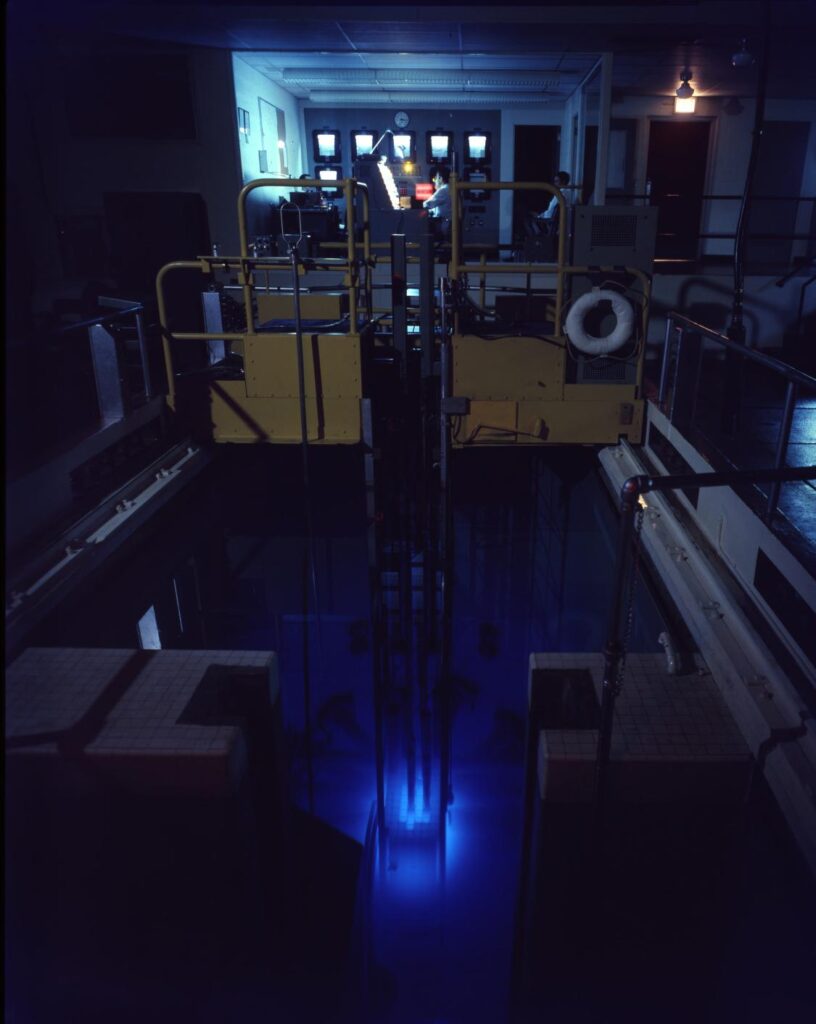

The Ford Nuclear Reactor pool and lab technicians, 1957.

Officially established in 1948, it was a living, continuous work, inviting researchers from all corners of the University. The new Memorial Phoenix Laboratory rose as one of the earliest buildings on North Campus, on what is now Bonisteel Boulevard. Construction began in the spring of 1954, and continued through 1956. Even once it was built, the reactor was predicted to take “six months or a year” to reach full power, before any studies could begin.

Up went lab spaces, a greenhouse, and, at the end furthest from the road, the Ford Nuclear Reactor. In 1957, “the beast,” as a few operators had taken to affectionately calling it, became fully operational.

“It worked!” announced a 1957 memo to the laboratory staff. Operating at two megawatts of power, the “icy blue glow” of the more than 55,000 gallon reactor pool (a product of Cherenkov radiation emanating from its fuel rods), would inspire the motto of the reactor workers: “M-Glow Blue!”

Project proposals flooded in—from archaeologists hoping to date coins and bones, to botanists hoping to study the effects of radiation exposure on plants, to doctors hoping to explore cures using radiant energy. Cancer treatment, bone grafts, freshwater mussels, medieval coins, and an Egyptian mummy were just some of the more than 800 subjects that the Phoenix Project helped to study. It spurred invention, too; the Phoenix-funded 1952 creation of the “bubble chamber,” a vessel of superheated liquid through which the delicate, spiraling paths of subatomic particles can be traced, earned U-M Physics ProfessorDonald Glaser the 1960 Nobel Prize.

Over the years, however, justifying the costs of running the reactor became more and more difficult. By 2000, academic uses of the reactor declined; governmental and industrial ones began taking their place. The University faced a hard decision. The project was too important to the U-M community to allow it to die. The Phoenix Project prepared to undergo a transformation to match its namesake.

Reactor operations stopped in 2003. Decommissioning was a complicated process. Which walls had tools hung on? Which surfaces had any radiation touched? These were the questions asked as the careful disassembly began. Lists were made. Soil and groundwater were sampled and tested. Thousands of cubic feet of high-density concrete were stripped from the empty pool where the reactor core was once suspended.

Technicians in white lab coats above the Ford Nuclear Reactor pool, 1957.

Once the building returned to levels of radiation deemed appropriate by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, it was reopened for use. The old nuclear reactor area, renovated, now serves as lab space for Nuclear Engineering research, with thick walls perfect for the work. In 2013, the greenhouse of the Phoenix Memorial Laboratory was replaced with a new, modern addition.

Still, if you go into the Laboratory lobby, you will see two enormous gray plaques on the wall. One lists donors, whose belief in the Memorial Phoenix Project made it real. The other plaque shares the names of staff, faculty, and students who gave their lives in World War II, featuring the words: “Dedicated to the study of peaceful uses of atomic energy.”

The Memorial Phoenix Project became the Michigan Memorial Phoenix Energy Institute in 2006, later shortened to the Energy Institute. Through cleaner energy, improved batteries and fuels, and better systems of transportation, the Energy Institute is still trying to improve the world today. It serves—much the way the Memorial Phoenix Project did—as an interdisciplinary hub for energy research at U-M.

A collection of Memorial Phoenix Project files is located at the Bentley Historical Library with information about the projects it funded, the history of its founding, and even a hand-drawn draft of the logo: a round nest of flames, and from it, the phoenix still rising.

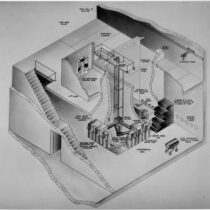

[Lead image: Photographic copy of cutaway view into nuclear reactor, HS2054]