Magazine

A Michigan Murder

More than 70 years ago, the sensational murder of State Senator Warren G. Hooper shook Michigan to its core, revealing a web of corrupt politicians, dubious lawyers, deadly Purple Gang members, shady prison wardens, and more. The Bentley has the papers of so many who were involved that when the case was re-opened in 1989, State Police demanded the Library turn over its materials. One of the biggest unsolved murders in the state’s history starts on a frigid day in 1945, and ends in rows of boxes at the Bentley, where there might still be a clue just waiting to be found.

by Lara Zielin

It was a bright, bitterly cold January day. The sun glinted off the fresh snow covering the Michigan countryside as State Senator Warren Hooper drove along highway M-99 from his office in Lansing to his home in Albion. He may have squinted against the blinding white landscape all around him, perhaps not at first seeing the car that would force him into the opposite lane. There were no oncoming cars since, after such a brutal spell of snow and cold, the roads were largely deserted.

Hooper skidded to a stop, his tires partially in snow, partially on pavement. The driver’s side door was yanked open, and Hooper was forced at gunpoint into the passenger seat. Hooper’s cigarette fell from his mouth as his hat was pulled down over his eyes, likely starting a small fire in the car. He may have screamed. Or perhaps he was simply too stunned to do anything much, not even turn his head as a bullet entered his left cheek, near the corner of his eye. Another bullet lodged behind his left ear. And another shattered through the top of his head. The assailant fled, and Hooper was left slumped in his seat on the side of the road. He was discovered by a feed elevator operator driving by a little while later.

The January 11, 1945 murder of Warren Hooper remains one of the most sensational murder cases in Michigan, and is unsolved to this day. In spite of massive state resources applied to catching the killer and countless leads, the trigger man never faced a jury for murder. What is certain about Hooper’s killing, however, is that it revealed a tangled web of conspiracy, corruption, and politics in Michigan.

One of the few crime scene photos shows the interior of Hooper’s car, which was badly burned. Police suspected a cigarette Hooper had been smoking had started the flames. Image courtesy of the Michigan State Police.

Hooper was killed four days before he was scheduled to testify before a grand jury about taking a bribe to alter a horse-racing bill. His testimony would directly implicate millionaire Frank McKay, a former state treasurer and prominent Republican who was the subject of three federal grand jury probes beginning in 1940.

Years later, in 1954, McKay would vigorously back a little-known Republican nominee for governor named Donald Leonard. Leonard was the former police commissioner who took over the Hooper murder case in 1947, increasing speculation that the Hooper murder remained unsolved not because of lack of evidence, but because some people simply wanted it that way.

Remarkably, the Bentley Historical Library has the files of McKay as well as Leonard, plus those of special prosecutor Kim Sigler, who fought for years to bring McKay to justice and tie him to the Hooper murder, and who would later become Michigan’s governor. The Bentley has so much material, in fact, that the Michigan State Police contacted the Library to request access to files when they reopened the Hooper murder case in 1989.

So don your fedora, grab a highball, and read all about how the Bentley sits at the heart of an unsolved mystery more than 70 years in the making.

Clues, Convicts, and Conspiracies

In 1945, news of Hooper’s murder traveled quickly, making headlines locally and nationally. Hooper had been Sigler’s key witness in a grand jury probe designed to put corrupt politicians behind bars. Armed with a renewed tenacity after Hooper’s death, Sigler now worked alongside police to piece together who pulled the trigger—and to tie it all back to McKay.

One of the first big breaks in the case came on January 13, when a 48-year-old grocery salesman named Harry Snyder claimed to have seen a maroon car blocking Hooper’s car on the highway, along with two men at the scene. In the Bentley archives is the map Snyder drew for law enforcement (see sketch above), showing how he drove up to the maroon car and got a good look at the fellow behind the wheel, and how he then spotted a second man at Hooper’s car. “It was as if [the second man] was talking to this fellow setting in the car, which afterwards I found out was the dead fellow, see,” Snyder told police. “The dead fellow sat with his head down like a drunk would.”

Snyder’s testimony was useful, but not concrete enough to lead to arrests. Then, in March, police caught another break when Sam Abramowitz, a convict with ties to Detroit’s Purple Gang, claimed that he and others had been hired by the head of the Purple Gang, Harry Fleisher, to kill Hooper.

By May, Harry Fleisher and his brother, Sammy, plus Detroit saloon operator Mike Selik and a small-time gambler named Pete Mahoney, were all charged with conspiring to kill Hooper. Abramowitz had turned state’s witness, pointing the finger at all the other men in exchange for immunity.

All four men pled not guilty and went to trial in July 1945, the courtroom hot and packed. Edward Kennedy Jr., defense counsel for Fleisher and Selik, repeatedly pointed out that Abramowitz had the same size feet as the tracks found at the murder scene, and that Sigler may well have given immunity to the assassin. “I really think you have made a mistake in this case, Kim,” he told Sigler. “I really do.”

The Perfect Alibi

In spite of any doubts raised, the Fleishers, Selik, and Mahoney were found guilty of conspiracy to commit murder and sentenced to four-to-five years in Jackson State Prison. But the charge of conspiracy didn’t account for who pulled the trigger and paid for the hit.

That question waited as Sigler tried again to nab McKay, putting him before the grand jury for conspiracy to violate state liquor laws. McKay was found not guilty, but Sigler’s name was nearly a household one by now, which no doubt helped him successfully run for governor of Michigan in 1946.

Sigler’s priorities shifted as governor, and the case stayed on the backburner until 1947, when inmates from the Southern Michigan Prison (now the Michigan State Prison) came forward with an incredible tale. Herman “Frenchie” Faubert and Mitchell Bonkowski told police that criminals—including Fleisher and Selik—were recruited to kill Hooper, and that they borrowed the maroon car of deputy prison warden D.C. Pettit to get to Hooper that day on highway M-99 (in addition to a second prison vehicle). There was, they said, an entire organized system of criminals going in and out of the prison with the help of guards, wardens, and even politicians, leaving many of them with the perfect alibi of being behind bars.

Leonard was skeptical about the tale, and reluctant to believe a convicted criminal. But Detroit Inspector George Kimball thought the case solved, and told the press as much. Newspaper headlines went back and forth about the veracity of the testimony, and Pettit was brought in for questioning multiple times. Police even searched for the murder weapon on his farm. Interestingly, all prison records for official car use on the day of Hooper’s murder were found missing.

Reopening the Case

Sigler often postured that no matter how long it might take, he’d bring Hooper’s murderer to justice. But as the years dragged on, the case got colder and colder. He lost his reelection bid for governor in 1948 and, in 1953, the plane that he was piloting crashed in Battle Creek.

The case was largely quiet until 1987, when Bruce A. Rubenstein and Lawrence E. Ziewacz published Three Bullets Sealed his Lips (Michigan State University Press), a thoroughly researched retelling of the Hooper murder. The book argued its own theory (a version involving Jackson Prison officials, Purple Gang members, and an inmate named Raymond Bernstein whom they claimed pulled the trigger) and posited that Sigler knew the truth of the case all along, but never revealed it for political reasons.

The dense information in the book, plus prodding from its authors, prompted Michigan State Police to reopen the case and to contact the Bentley Historical Library, which Rubenstein and Ziewacz had used extensively in their research.

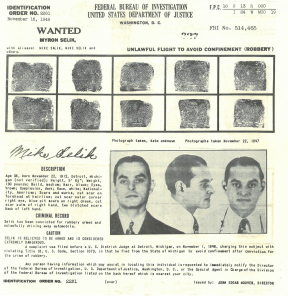

The FBI put Mike Selik on its wanted list after he jumped bail, soon after being convicted of conspiracy to murder Warren Hooper. He was found three years later in Brooklyn, New York.

“The Michigan Department of State Police has recently reactivated the [Hooper] investigation and would like the University of Michigan to return any items which are official State Police documents to aid us in our investigation,” wrote Michigan State Police Director R.T. Davis in a letter to the Bentley dated March 9, 1989.

The Bentley digitized everything in the Donald Leonard files and sent it all to Detective Sargent Chet Wilson, who spoke to the Bentley recently from his home in Traverse City.

“I came to a different conclusion than the [Three Bullets] authors,” says the now-retired Wilson. When the case was re-opened, he researched old police records and identified people connected to the murder who were still alive. One in particular stands out in his mind: Mike Selik.

Wilson interviewed Selik at a retirement community on May 5, 1989. “I went to his residence without giving him any notice I was coming,” Wilson says. “His expression was of complete shock. He nearly had a panic attack; he couldn’t hardly answer any questions I asked.”

A Freedom of Information Act request for Wilson’s case files on the Hooper murder indicate that Wilson tried to convince Selik to come clean about what had happened “due to the fact that he was one of the last remaining persons that had personal knowledge as to what actually occurred,” according to the filed report. But Selik wouldn’t budge. “He stated that he didn’t talk [during the grand jury trial in 1945] and he is not going to talk about it now,” Wilson wrote in his report.

Speaking with the Bentley, Wilson recalls that he left Selik his card and told him to call if he changed his mind. “[Selik] was involved, if not the trigger man,” Wilson believes.

Wilson and other investigators continued the hunt, conducting ballistic tests on possible murder weapons, including two guns from Southern Michigan Prison. However, no conclusions were ever reached. Selik died in 1996 having never followed up with Wilson, and as time marches on, it’s less and less likely the killer will ever be uncovered.

“In today’s time, it might be possible to get DNA from the crime,” says Wilson, but few physical clues from the case remain. The Michigan Historical Museum has the hat Hooper wore when he was killed, and they displayed it in 2010 during the debut of a novel inspired by the case, To Account for Murder by William C. Whitbeck (Permanent Press). But 70 years on, it’s hard to say what DNA could remain, save possibly Hooper’s.

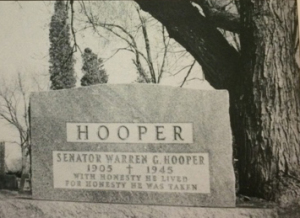

Hooper can’t tell us who his assailant was, but his grave in Albion’s Riverside Cemetery marks the fact that he died trying to do the right thing.

“With honesty he lived,” his tomb-stone reads, “for honesty he was taken.”

The Lineup

Who’s Who in the Hooper Murder Case*

Frank McKay A millionaire and prominent Michigan Republican who was suspected of ordering the hit on Hooper. The Bentley has his papers.

Donald Leonard A Michigan State police officer who became State Police Commissioner in 1947 and took over the Hooper investigation. The Bentley has his papers.

Kim Sigler Grand jury special prosecutor who worked hard to tie Frank McKay to the Hooper murder. He served as Michigan’s governor from 1947 to 1948. The Bentley has his papers.

Harry Snyder A witness who tied a maroon car to the murder scene in 1945. The maroon car was later thought to belong to D.C. Pettit, deputy prison warden for the Southern Michigan Prison.

Sam Abramowitz Purple Gang member turned state’s witness who claimed that he and others had been hired to kill Hooper. He received immunity in exchange for his testimony. His feet were the same size as footprints found at the crime, leading some to believe he was the actual killer.

Harry Fleisher A Detroit mobster at the helm of the Purple Gang at the time of Hooper’s murder. He was found guilty (along with his brother Sammy Fleisher, Mike Selik, and Pete Mahoney) of conspiracy to commit murder in 1945.

Mike Selik A Detroit bar operator who was convicted of conspiracy to commit murder in 1945. Selik was one of the last living people with personal knowledge of the case when it was reopened in 1989. Detective Sargent Chet Wilson questioned Selik about the case in ’89 and believes Selik was indeed involved, if not the trigger man.

* The list of suspects in this case is much longer, and more tangled, than this short article could allow. For a full picture of the investigation and grand jury trial, please see Three Bullets Sealed his Lips by Bruce A. Rubenstein and Lawrence E. Ziewacz.