Magazine

An Arctic Escape

With the world watching, two pilots went down over Greenland in 1928. Their rescue would hinge on William Hobbs, a professor-turned-adventurer leading U-M’s Greenland Expedition. His papers at the Bentley reveal how, in order to get everyone out alive, he’d have to face peril again and again.

By Madeleine Bradford

The sky was clear, the runway was ready, but the Rockford Fliers were late.

As night drifted down over Greenland’s frozen landscape, the landing strip near Camp Lloyd glimmered with lanterns, illuminating the worried faces of the 1928 University of Michigan Greenland Expedition team. They squinted upwards, waiting for the rasping buzz of a monoplane engine, or the flicker of the Greater Rockford’s shadow. Perhaps it would only be another 10 minutes. Another hour. Another two hours. They waited.

No plane arrived.

Radio signals from the Greater Rockford stopped abruptly over the freezing Labrador Sea, according to the New York Times. A group of churchgoers spotted the plane flying inland near Qeqertarsuatsiaat (a name that roughly translates to “Rather Large Islands”) on Greenland’s southwestern coast, so the plane had likely made it to shore. That was all anyone knew.

Worry mounted. Radios tuned in to hear any signals the Fliers might send. Boats scoured the coast, and search-and-rescue teams worked to cover the land. Local hunters searched for the Fliers in the wilderness. Newspapers speculated: maybe the Fliers were stranded, injured, or dead. Maybe they would turn up tomorrow.

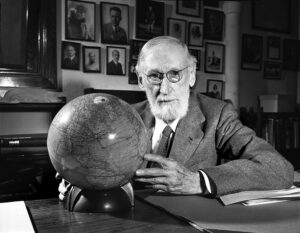

Professor William Hobbs with globe, HS19468.

Professor William Herbert Hobbs, the bristle-bearded adventurer leading the University of Michigan’s Greenland Expedition, knew intimately the dangers a wrecked plane could be facing on the ice. Trekking the Arctic, tracking pilot balloons, Hobbs’ expeditions had hunted information about Greenland’s glacial winds since 1926.

Hobbs knew it was a treacherous place to be stranded, and the window of survival was narrowing. A false report said the Fliers had been spotted even farther south—too far away to reach Hobbs and his men alive. Nothing more was heard for days. Then weeks.

“After two weeks of this suspense, we became convinced that [they] must have perished,” Hobbs wrote in his autobiography, An Explorer-Scientist’s Pilgrimage. That was when smoke from the Rockford Fliers’ campfire broke the skyline.

Hobbs and the Barnstormers

The Rockford Fliers were Parker “Shorty” Cramer and Bert “Fish” Hassell, two lifelong aviators; “barnstormers who flew by the seat of their pants and the Grace of God,” in Hassell’s own words. Their stop in Greenland was part of a plan to prove the potential of the Great Circle Route from North America to Europe, by following the Earth’s curve directly between the two continents. They chose a course to Stockholm from Rockford, Illinois, the town that gave them their name.

This route was relatively untested. They were planning very few stops for fuel. It was dangerous, but head pilot “Fish” Hassell had gotten his nickname by crashing his plane into Lake Michigan and swimming to shore; he was not afraid of a risky flight.

Of course, when plotting a global journey, who better to ask for advice than the Head of Geology at the University of Michigan, Professor Hobbs? An explorer himself, Hobbs knew the world; he’d seen most of it. Moreover, he never shied away from answering questions that were asked of him—or answering ones that weren’t.

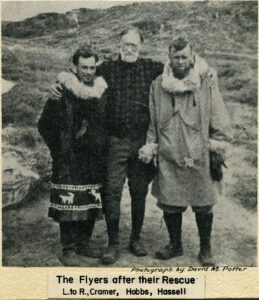

Hobbs (center) and the pilots he helped rescue: Cramer (left) and Hassell (right), HS19725.

Hobbs eagerly gave his opinions of other explorers, proclaimed which of his colleagues he believed were enemy sympathizers (accusations that cost those men their jobs during World War I), and shared his thoughts on the best presidential candidate (certainly not Woodrow Wilson, he’d quickly tell you, in 1912). Depending on who you spoke to, he was an overzealous hothead, or a patriot. Certainly, he could never be accused of being shy.

So when the Fliers asked for advice about their trip, he responded. One of their refueling stops should be on the coastal flats of Greenland, he told them. As head of the Greenland Expedition, he was in a unique position to help.

Hobbs was motivated by more than just altruism. He hoped the Rockford Fliers would prove that Greenland could serve as a stopover for air travel to Europe. He also saw the scientific potential of the flight: the Fliers agreed to bring a meteorograph with them on their journey. For Hobbs, this was a tantalizing potential source of new data regarding wind patterns high above the ice cap. The Fliers could whisk the information from the air as they flew.

Hobbs wasn’t the only one invested in the flight’s outcome. The New York Times estimated that 20 percent or more of the population of Rockford, Illinois, chipped in to help buy the Fliers their Stinson monoplane, the Greater Rockford, in a version of early crowdfunding.

It took some persuasion.

“Nobody would believe us when we told them we wanted to go to Sweden from Rockford the shortest way. . . . They said we were bushed. We drew maps for them on tablecloths and wrapping paper and we argued until our tongues were flapped out,” Hassell told the Evening Star in 1944. The arguments paid off. The plane was purchased. After one false start that ended in a cornfield crash, Rockford residents watched, heads tilted skyward in late summer 1928, as the Greater Rockford disappeared into the clouds.

Mayday, Mayday

The Rockford Fliers set out for Greenland on August 18 in fine weather. Their first pit stop, in Cochrane, Ontario, went smoothly.

Over the Labrador Sea, however, thick clouds bloomed around them; gale winds swung the plane offtrack. Fuel dwindling, they stuttered through the air, dipping dangerously low.

They scanned the harsh Greenland landscape frantically for signs of Hobbs’ crew. Eventually, lack of fuel forced them down on the Maniitsoq Ice Cap (“Place of Rugged Terrain”), far south of the landing zone.

The world that the Rockford Fliers now faced was sharp and cold, cut by thundering glacial rivers and deep crevasses. Yet they believed they were close to Hobbs’ location, Hassell later told the New York Times. They expected the walk would take a single day.

It took two weeks.

No Smoke Without Fire

Professor Hobbs heard it before he saw it: one of his expedition’s little boats, humming in the storm-tossed fjord. Throwing down the pack he’d been carrying to their weather observatory inland, he rushed back to camp to demand explanations. No one had asked permission to head into the fjord. Hobbs was furious. More than that, he was frightened. On the water, a storm was rising.

At Camp Lloyd, he was greeted by a group of native Greenlanders who had seen a plume of smoke in the distance. If it was a campfire, the Rockford Fliers might be alive. Hearing that, Elmer Etes, the Fliers’ friend, and Duncan Stewart Jr., assistant geologist, immediately leapt into the expedition’s motorboat and set off into the fjord. Never mind the waves, or the wind.

Standing onshore, Hobbs’ dread overtook him; he later called the moment “interminable.” They stood a chance of losing not just the Fliers, but now Etes and Stewart.

Sputtering flashes pierced the darkness. First, a flare gun; then a quick signal in Morse code—the Fliers were alive! Hobbs’ men lit a lantern over the camp as a makeshift lighthouse. When the motorboat was near shore, Hobbs and his crew waded into the freezing water. They helped haul the Fliers back onto land. As soon as the Fliers were safe, Hobbs raced to send a message to the New York Times, to tell the waiting world and the Fliers’ families: they had survived!

It was a miracle, but none of them knew how much trouble still awaited them. Home free?

Not even close.

A Leader of Shipwrecked Men

Hobbs decided to travel with the Fliers back to Nuuk, the capital of Greenland, along with a portion of the expedition’s crew. Two days after the rescue, all boarded the Nakuak, a motorized sailing ship, or “sloop,” around nightfall. Weary and wave-rocked, they fell quickly asleep.

At the helm, near dawn, so did their skipper.

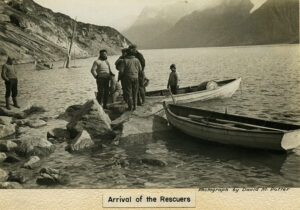

Hobbs and the Rockford Fliers survive the sinking of the ship, the Nakuak, HS19726.

With a horrible jolt, the Nakuak cracked open against a reef. Water churned in. Startled awake, some rushed to wedge anchor flukes into nearby rocks, while others scrambled to bring their supplies out of the hold.

Hobbs found himself a leader of shipwrecked men. They were lucky, he knew; they had food, tents, and sleeping bags. Everyone lived. A dinghy with two crewmembers had been sent to get help. Still, after a few days, Hobbs began to fear that the dinghy hadn’t made it. He started the fatal calculations. How much food was there? How many people? How long, exactly, did they have?

Just as they were about to begin rationing, the motor sloop Nipisak arrived. Relieved, and exhausted, the men climbed aboard.

Hobbs and the Fliers were offered the use of the Nipisak for the remainder of their journey to Nuuk. They accepted. They soon wished they hadn’t. The motor stopped and started, and the winds drove them sharply back and forth between the sea and the reefs.

When the Nipisak finally made it through, the delay had cost them. The freighter Hobbs had intended to book for passage toward Copenhagen was already full. They turned to the tramp freighter Fulton instead. The ship held no bunks, but plenty of ore, which clanged thunderously against the metal siding as they bucked through the rough seas.

Most of their party slept on the floor, “where they rolled about like peas with the tossing of the ship,” Hobbs remembered. Dishes clattered. Ink bottles smashed. Supplies were jumbled about.

They reached Copenhagen safe but shaken. The Scandinavian-American steamship line brought the Fliers back to New York, but Hobbs went separately on the ocean liner Olympic, only to pass through another massive storm. “Only once, when riding out a typhoon in the Sea of Japan, have I seen a more angry sea,” he reminisced.

Despite everything, Hobbs and the Fliers believed their trip successful. The Fliers’ runway in Greenland was later transformed, at Hobbs’ recommendation, into the U.S. airfield Bluie West-8 in World War II—one of several such airfields placed strategically throughout Greenland at Hobbs’ advice. Later still, the airfield became Greenland’s Kangerlussuaq Airport. For his work in World War II, France appointed Hobbs a Chevalier of the Legion of Honor. Researching Greenland’s weather patterns also made Hobbs among the first to record instances of katabatic winds: cool, dense air sliding quickly downhill.

The story of the Greater Rockford doesn’t end on the ice. The abandoned monoplane was rescued in 1968 and resides today, restored, in the Midway Village Museum in Rockford.

Project Runway

In 2006 and 2019, expeditions of students and faculty from the University of Michigan and other institutions followed the footsteps of the 1926 Greenland Expedition, studying climate change. Meteorology specialist Professor Perry Samson led these expeditions alongside U-M Professors Mark Flanner, Jeremy Bassis, and Virginia Tech Professor Bob Clauer. Their students saw glaciers crumbling, studied the winds, learned history, and raised awareness about the impacts of climate change.

The base for their work was Kangerlussuaq. The Fliers’ old runway is now a hub of travel in Greenland, receiving visitors and arctic researchers alike.

Digital photographs of the 2006 expedition’s work have been donated to the Bentley Historical Library by Professor Samson. He and his colleagues plan to donate additional materials from 2019 as well, including 3-D views of Hobbs’ old weather observatory in Greenland, at the top of Mt. Evans.