Magazine

An Ill-Fated Voyage

Fifty years ago, the Edmund Fitzgerald freighter sank beneath the waves of Lake Superior. Ric Mixter’s research into the wreck is archived at the Bentley, ready to help the next generation of shipwreck enthusiasts.

By Lara Zielin

The November gale was whipping Lake Superior into a frenzy. The ship Arthur M. Anderson was sailing into waves as high as 30 feet, while 50-knot winds howled.

Arthur M. Anderson’s captain, Bernie Cooper, was in touch with a nearby vessel, whose captain had reported damage from the storm. The other captain reported that his ship’s radar was out, the sump pumps were running, but nothing appeared too amiss.

“We’re holding our own,” the other captain radioed.

Cooper thought everything was fine. He never suspected that a short time later, captain Ernest McSorley and his ship, the Edmund Fitzgerald, would be gone beneath the waves. The entire crew, 29 men total, would die on November 10, 1975, in a Great Lakes’ maritime disaster.

Shipwreck researcher and historian Ric Mixter has spent decades investigating what factors contributed to the Edmund Fitzgerald tragedy and wrote a book of his findings called Tattletale Sounds: The Edmund Fitzgerald Investigation (Airworthy Productions, 2022). Today, his in-depth research on the topic is archived at the Bentley Historical Library.

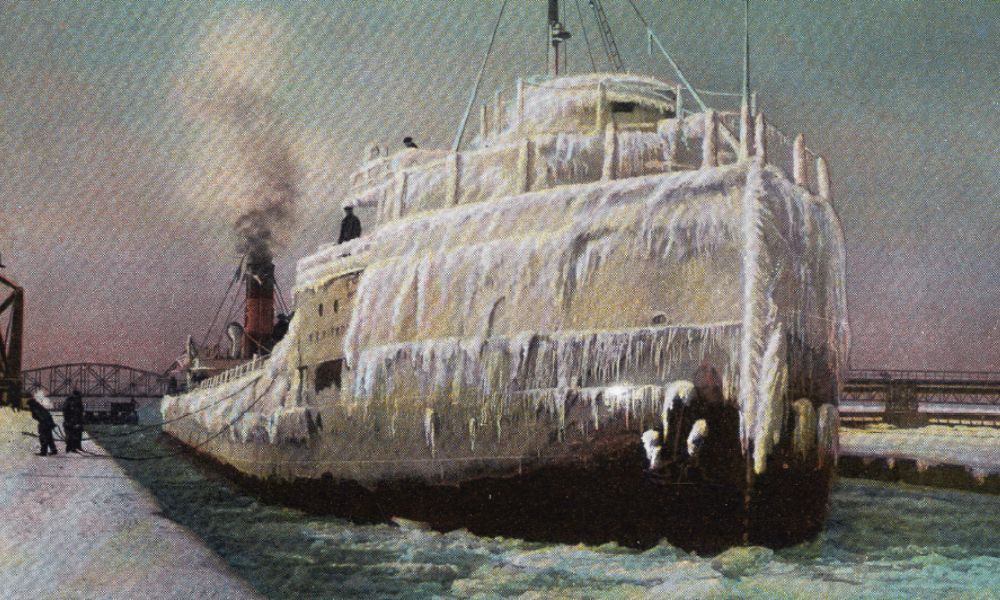

An archived postcard of the Edmund Fitzgerald locking down in December after a seventy-two hour battle with a zero storm on Lake Superior.

“One factor is that just about everyone misjudged the storm’s speed,” says Mixter, a former journalist who has appeared as a shipwreck expert on the History and Discovery channels. “That storm went across Lake Superior about an hour faster than anyone expected. Captain McSorley could have stopped at several places to shelter but he thought he could make it down to Whitefish Point (Michigan).”

McSorley also had a track record for pushing the ship to its limits. Nicknamed the Toledo Express, the Edmund Fitzgerald had been setting records for both speed and how much it could carry. “McSorley really believed that the ship was infallible,” Mixter says. This, despite documentation that the ship had a loose keel and its hatch covers were compromised, even before it left Superior, Wisconsin, on its ill-fated route. “I think McSorley pushed that ship every year and it finally caught him,” says Mixter.

Mixter even got a closeup look at the damage to the ship when he dove the wreck in 1994. Underwater he could see firsthand the mangled hatch covers. The ship itself was in two pieces.

Back on dry land, Mixter unearthed documentary footage at the Bentley of the ship being constructed and interviewed the ship’s builders. He also interviewed ship captains on the lake the night the Edmund Fitzgerald sank, additional divers who explored the wreck, and many others. His work comprises decades of research that will now be available at the Bentley for anyone to explore.

“I’m so glad I had experts at the Bentley to guide me because it’s so easy to miss things, and now my own research can be there to help guide others,” Mixter says.

It’s likely his papers will grow as he continues to amass evidence and research about the Edmund Fitzgerald and other shipwrecks. “As I do more research and projects, I’ll definitely be adding to the collection,” he says.