Magazine

Angell in the 21st Century

The newly digitized papers of U-M President James Angell show his influence in higher education and beyond.

by Lara Zielin

James B. Angell arrived in Ann Arbor with his family in September 1871. The Board of Regents had elected him president of the University of Michigan, though the negotiations had taken time and numerous back-and-forth letters—many of which are archived in Angell’s collection at the Bentley Historical Library.

“It seems to me to need absolutely, paper and paint, bath room [sic] with hot and cold water, water closet, and some arrangement for a dining room closet, and a furnace,” Angell wrote of the president’s house, which would undergo an extensive renovation in advance of his arrival. He also held out for a better salary: $4,500 annually, to which the Regents ultimately agreed.

Angell was more than worth it. He would transform not only the University of Michigan, but the face of higher education writ large.

“Angell was a linchpin in the evolution of the research university,” says Mark Nemec (’00), who is the President of Fairfield University and who studied the Angell papers for his Ph.D. dissertation in political science from the University of Michigan.

“He recognized that the university couldn’t take its privileged place in society for granted. It needed to demonstrate its relevance, though I don’t think that’s a word that Angell would use.” Nemec’s book, Ivory Towers and Nationalist Minds: Universities, Leadership, and the Development of the American State (University of Michigan Press, 2006), outlines Angell’s contributions to higher education, policy, democracy, diplomacy, and more.

“One way was through his support for and expansion of admission by diploma, where the University of Michigan would accredit high schools in Michigan and elsewhere, even as far west as California, to help set university admission standards. And secondly, he was willing to join the Association of American Universities at its founding in 1900, and was influential about getting skeptics, such as Arthur Twining Hadley (President of Yale), to join. He was an opinion leader among the university presidents.”

Angell both built and strengthened the University—hiring modern research faculty like philosopher John Dewey, economist Henry Carter Adams, and chemist Moses Gomberg—and served as an important adviser to other higher education leaders around the country.

In the Angell collection, which has been newly digitized and made available online, researchers can read decades’ worth of letters to Angell from his peers. The digitization was completed in partnership with MLibrary, which supports and hosts the content.

“Angell had all the respect of the established universities of the East, but he also had the respect of those starting newer universities in the West,” Nemec says. “They all wrote to him looking for guidance, recommendations, and advice.”

Angell served as University of Michigan president until submitting his resignation in 1905. The Regents wouldn’t accept it until 1909. He lived in the house he’d once diligently negotiated to renovate until his death in 1916.

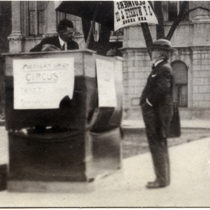

Lead photo: A student sells a ticket for the Michigan Union Circus to President James B. Angell circa 1912. HS17044.