Magazine

Beyond These Hallowed Halls

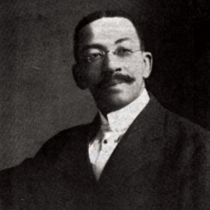

In 1899, Oscar W. Baker Sr. was accepted into the University of Michigan Law School, becoming the 100th African American student to attend U-M. After graduation, Baker would make remarkable contributions and achievements working for racial and social justice. The Bentley’s new African American Student Project helps fill in some of the information about this exceptional alum.

By Margaret Leary

In the late 1800s, the town of Bay City, Michigan, was thriving.

Its location, where the Saginaw River flows into the Saginaw Bay of Lake Huron, had proven ideal for lumbering, shipbuilding, coal mining, salt production, and the sugar-beet industry. Railroads augmented the rivers, connecting Bay City by land to the rest of the country.

In 1885, six-year-old Oscar W. Baker was chasing friends along the Pere Marquette train tracks when, at the crossing of Jefferson and 11th Streets, he stumbled and fell. He was struck by an oncoming train and nearly killed. The train cut off part of his leg, which soon had to be removed to the hip. His father, James H. Baker—one of the first African Americans in Bay City, who had been a barber, owned a local restaurant, and had run for office in town—sued the railroad. He won a then-enormous $5,000 judgment.

Young Oscar was a crucial witness in the trial, examined and cross-examined by the lawyers. One of the lawyers predicted his future: “He . . . was and is . . . prevented from doing any work and from attending school, and is, and always will be, hindered and disabled from earning his own living . . . .”

Oscar proved this prediction completely wrong. He would become a sought-after lawyer, fighting racial prejudice and becoming the first president of the Bay City NAACP. At one point in his career, Oscar helped Black women such as Marjorie Franklin achieve fair housing at the University of Michigan, representing Franklin when she fought to live in Couzens Hall.

The Bentley’s new African American Student Project database has helped fill in more details about Oscar’s life, revealing his remarkable contributions and achievements working for racial and social justice.

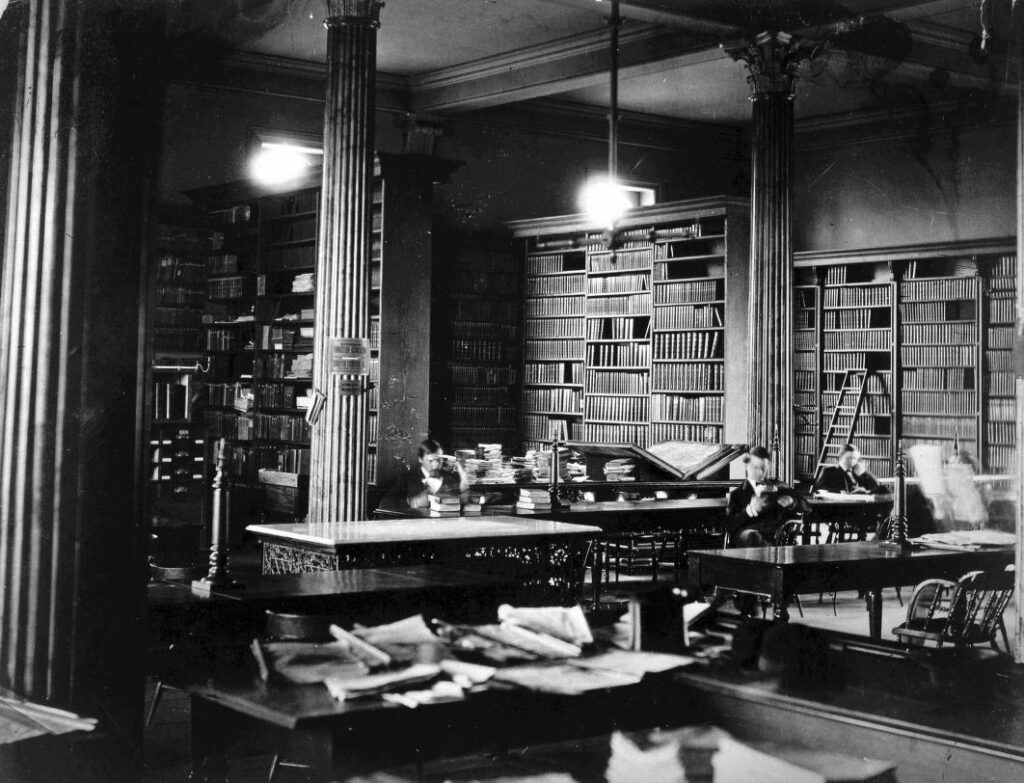

Interior of the U-M Law Library at the turn of the century, close to the time Oscar Baker would have been a student at U-M. [BL000087]

Early Career

Oscar finished high school at age 19, then attended the Bay City Business School to learn typing and shorthand. In 1899, he was accepted into the University of Michigan Law School, becoming the 100th African American to attend U-M.

Money was tight, however, because Oscar’s father had poorly invested the $5,000 judgment funds from the railroad accident. To earn tuition money, Oscar was an office assistant for Lt. Governor Orrin W. Robinson, using the typing and stenographic skills he had learned in business school.

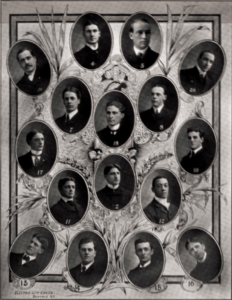

The 1902 Michiganensian yearbook featured images of the Law School’s graduating class, including Oscar Baker, number 12.

Oscar later became a member of Alpha Phi Alpha, an African American fraternity, probably joining as an alum since the U-M chapter didn’t form until 1906. Student directories show him living at 217 N. First Street, about a mile west of campus, in the segregated area of Ann Arbor, where many African American homes and churches were located. He graduated in 1902 and had his law license. But how to set up an office, with no resources?

A white lawyer, Lee Joslyn, offered Oscar the extra desk in his Bay City office and said Oscar could take any case that walked in when Joslyn was absent. The invitation made the law firm the first integrated law firm in the state. Oscar made his “maiden plea” in police court in August 1902 and, although he lost, his arguments were so eloquent that the West Bay Times newspaper called him “one of the coming young attorneys of this city.”

An early case that Oscar brought was an attempt to recover the $5,000 his father had lost. His father had acted as the “next friend” of his minor son, and Oscar learned in law school that the railroad may have erred in making the payment without bond, which was not required at the time. Oscar ultimately lost that case but may have won a bigger victory: As a result of the litigation, insurance companies and railroads began to require a guardian, who would be responsible to the minor and had to post a bond, to be appointed for minors involved in civil suits.

Fighting for Racial Justice

At age 35, Oscar became the President of the Michigan Freedmen’s Progress Commission, an organization that produced the Michigan Manual of Freedmen’s Progress. The Manual chronicled in pictures, stories, and documents the progress of African Americans in Michigan 50 years after the abolition of slavery.

Commissioned by the State of Michigan and paid for by the Michigan legislature, the Manual became a comprehensive catalog of accomplishments by Michigan African Americans. It listed doctors, lawyers, clergy, dentists, nurses, musicians, and other professions; highlighted volunteer service in the military; chronicled Michigan politicians; and more. It showed hundreds of photographs of individuals, buildings, houses, as well as lists of patents and inventions, plus facts about the relative health and mortality of African Americans and whites in Michigan.

Another of the Manual’s goals was to provide evidence of press bias against African Americans in four daily Detroit papers. The analysis showed that of 232 documented articles, only 36 were “commendatory,” while 139 were about “criminal” African Americans.

The Manual also supported the Michigan delegation to the Half Century Anniversary of Negro Freedman event in Chicago, from August 22 to September 15, 1915. Popularly known as the “Lincoln Jubilee and Fifty Years of Freedom” celebration, it attracted thousands of attendees, culminating in a crowd of 22,000 to hear Chicago Mayor William Thompson at the closing.

The delegation’s timing was significant: Reconstruction had long ended, Jim Crow was flourishing, and the KKK would soon be established in Michigan. That Oscar was chosen to help produce the Manual and attend the delegation illustrates the deep trust his community placed in him, and it elevated his profile across the state and nationally.

Oscar also protested prejudice against other minorities. When an ad published by a Michigan resort asked for gentiles only, Oscar wrote a letter to the editor of a local Bay City paper arguing the resort’s ad violated the Civil Rights statute of Michigan.

When a local branch of the NAACP was organized in Bay City in 1919, Oscar was its president. He maintained contact with the national NAACP and advised them about lawyers who could join Clarence Darrow in representing Ossian Sweet (in 1925) and later Henry Sweet (in 1926), when the men were accused of murder after defending the home Ossian had purchased in a white Detroit neighborhood. Shortly after the Sweets occupied the house, an angry white mob threatened from the front yard. The police who were present did nothing, and a gun fired from an upper story of the house killed one white man and wounded another. The trials were sensational and highly publicized. Both Sweet men were found not guilty, in part due to the recommendations for good legal counsel, which Oscar helped provide.

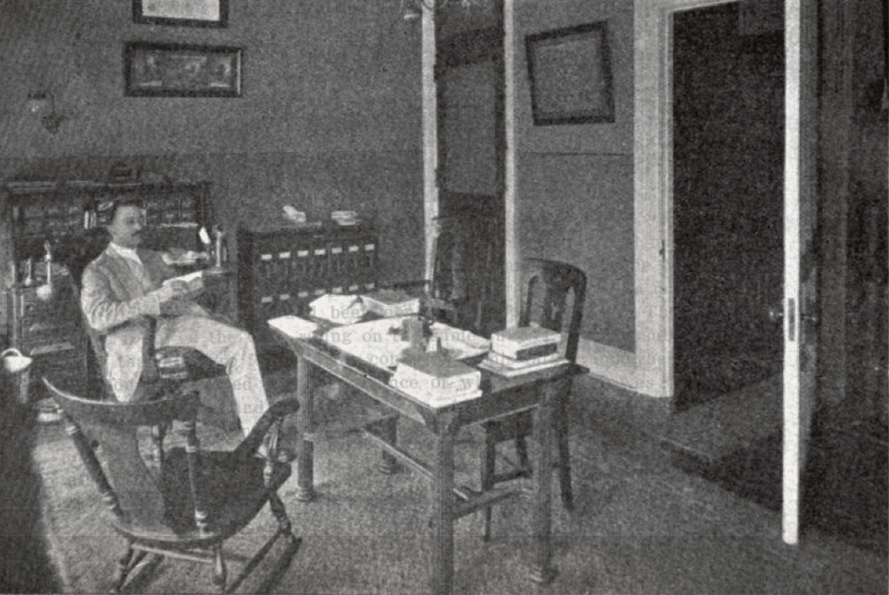

Baker working in his Bay City office, photo undated. [Michigan Manual of Freedmen’s Progress]

Local Politics

Oscar continued to support having a branch of the NAACP in Bay City, despite his opinion that “there is little need for such an organization. Prejudice is at a minimum and personally I have very little difficulty in getting by in the courts . . . . There is little prejudice in the theatres, cafes, etc. and the people live in harmony one with the other, so far as the races are concerned.”

Then, in 1951, as a member of the Bay County Bar Association, he voted to expel anyone who “professes membership in the Communist party.” The local Bay City paper ran the headline: “Bar Will Expel Reds; Action is Believed First in Michigan.” The next year, Baker continued to serve on a special advisory committee of the American Bar Association to study the strategy and tactics of Communists. It was ostensibly part of the association’s work to combat Communist infiltration of lawyers’ ranks.

Oscar made headlines again in the fall of 1952 by switching political parties. The local paper reported that Baker, a “pioneer attorney and leading Republican figure in the State for more than 50 years,” had repudiated Republican gubernatorial candidate Fred Alger and would support the re-election of Democratic Governor G. Mennen Williams. His reason? “Williams has been one of the fairest and most liberal governors for the minorities and the common man in his memory.”

Oscar continued to build his career in Bay County and more widely. He was the first African American to be elected head of the Bay County Bar Association, he was vice-president of the Bay County Recreation Commission, and he was a member of the Board of Control of the Bay City Amateur Baseball Federation. He and his family often enjoyed a month at Idlewild, a resort in northwest Michigan. It was one of the few resorts where African Americans could join and own property.

Two of his nine children, Oscar Jr. and James Weldon, earned law degrees from the University of Michigan, and Oscar Jr. continued the family practice. Generations of Bakers have continued to attend the University, including fourth-generation twins David and Nathaniel Cade, who earned J.D.s in 1996, and their cousin, David Baker Lewis, who earned his J.D. in 1971.

Today, the University of Michigan Law School offers the Oscar Baker Sr. scholarship to commemorate his legacy and to support African Americans attending the La w School.

Sources for this story include:

The African American Student Project website (aasp.bentley.umich.edu). Bay City Times Historical and Current, 1889–Present. Professor Edward J. Littlejohn’s archives, Walter Reuther Library at Wayne State University, as well as Littlejohn’s books and articles about African American lawyers. Black Studies Center and Historical Newspapers (ProQuest).

[Thumbnail image at the top of the story: Oscar Baker portrait from the Michigan Manual of Freedmen’s Progress.]