Magazine

Cold War, Warm Welcome

In 1961, the Kennedy Ad-ministration sent the U-M Symphony Band to the Soviet Union in hopes of thawing relations between the two countries through the common language of music. Could young musicians succeed as diplomats?

By Katie Vloet

The two men met for the first time with a bear hug. They did not speak the same language, so the local man pantomimed— somehow—that he was a performer and teacher of the trombone, euphonium, and trumpet. The visitor responded with arm gestures that indicated he’d been a violinist.

One can imagine their arms flailing and faces growing animated with their wordless storytelling. They went on to discuss the visitor’s symphony band and its instrumentation, performances, and repertoire, all without a shared spoken language.

This was 1961 in the Soviet Union, and the local man was renowned conductor Natan Rakhlin of the Ukrainian Symphony. The visitor was William Revelli, the longtime director of the University of Michigan bands, who was conducting the Symphony Band in a series of concerts throughout the Soviet Union, Eastern Europe, and the Near East.

“Harry Barnes, our representative from the U.S. Department of State, entered the room and stood amazed that two men who had never previously met, could carry on such an extensive conversation without knowing a single word of each other’s native language,” Revelli later recalled. “Maestro [Rakhlin] attended three additional concerts and came to visit me following each performance. Our friendship for each other continued to grow, as did our ‘vocabulary’; great and far-reaching indeed is the language of music.”

That moment of shared humanity was exactly the kind of connection that led the State Department under the Kennedy administration to fund the 15-week trip, still the longest trip of its kind sponsored by the department. The tour occurred during the height of the Cold War, with the goal of answering this question: Could young musicians really succeed as diplomats?

Planes, Trains, and Camels

They sported bouffants and flat-tops, horn-rimmed and brow-line glasses, trench coats, and head scarves. Of the 94 students who toured with the symphony band, many had never traveled internationally or sent airmail.

“I had never been on an airplane. And all of a sudden, we spent 15 weeks on airplanes, trains, buses, taxi cabs, camels— you name it,” trumpeter Dave Wolter recalled decades later.

Their first show was in Moscow. Before a crowd of 6,000, they concluded their two-hour performance with a Russian classic, “Great Gate of Kiev” by Modest Mussorgsky. Revelli and the band members waited for applause. They were greeted with silence.

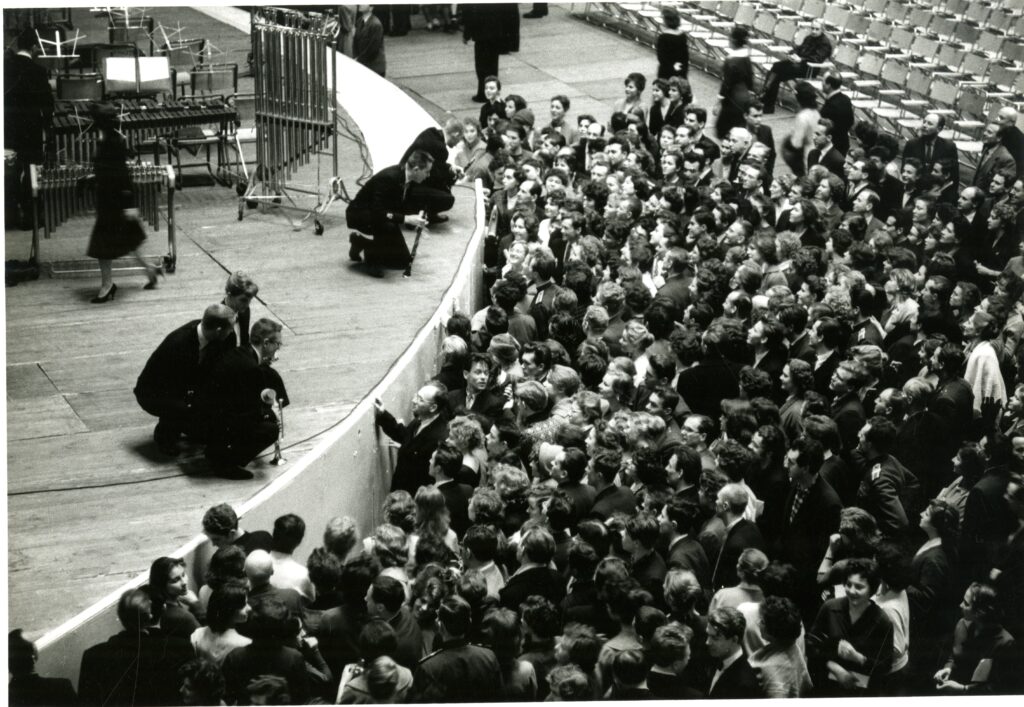

After performances, audience members often wanted to speak with the musicians. (U-M Symphony Band 1961 Tour collection)

At first, Revelli and many students thought they had done something wrong. Some wondered if they had offended the very people they were in Moscow to engage in friendly, cross-cultural harmony. Then, a single Muscovite rose. He clapped once, followed by a single clap from many in the audience. They stamped their feet, clapped more, and were rewarded with five encores.

The unusual reception greeted them throughout the country. “11th day, Leningrad,” band member Loren Mayhew wrote in a diary that is now kept in the Bentley archives. “We performed our final concert in Leningrad tonight. We played the longest [concert] yet. Although we did not play any songs over, we played 8 encores, which accounts for the extra time. After the concert I talked to some people from the audience. The [S]oviet people are wonderful and if you mention the word ‘peace,’ they go wild in applause.”

Peace, Love, and Understanding

The band members were not immune to international politics during the trip. When they were in Cairo, for instance, they were quarantined due to demonstrations against the United States’ recent Bay of Pigs invasion in Cuba, recalled Bruce Galbraith, one of the band members who later organized a reunion trip in 2012.

The reunited band members were also honored at a halftime show during a 2011 Michigan football game. That’s when Kari Lindquist, then a saxophone player in the Marching Band, first learned of the trip. She is now a Ph.D. student at the University of North Carolina and is studying the trip as part of her research into tours of U.S. wind bands abroad during geopolitical conflicts in the 20th century. The U-M Symphony Band’s tour, she says, was only possible because of the Lacy-Zarubin Agreement of 1958 that allowed for cultural exchanges between the United States and Soviet Union.

Of note, says Lindquist, is the fact that women musicians were allowed to play on the trip—at a time when they were not permitted to perform in the Marching Band (that wouldn’t happen until 1972). The trip was a success for a variety of reasons, she says—not least of which were the casual interactions between musicians and audiences. “The young people were a big asset to what the State Department was trying to achieve,” she says.

The outcome of the trip can be measured in rounds of applause, or audience numbers. It can be assessed by this statement in the Congressional Record: “Their talent has carried a message that no words could have expressed,” or this review by a conductor in the Soviet press: “First to say about the band: it has a perfect sound. . . . No wonder our keen audience showed so much attention and gave a warm welcome to these messengers of goodwill from the American people.”

It could also be measured in smaller moments, the kind of diplomacy that is only achieved when one human being meets another.

On February 27, 1961, Mayhew—the diarist referenced previously—wrote of meeting a Soviet French hornist at a hotel in Leningrad. They used Mayhew’s English-Russian dictionary to communicate.

Fifty years later, Bentley archivist Olga Virakhovskaya would accompany some band members on a reunion trip to Russia, which had been organized and led by 1961 band member Galbraith. She thought she could try to contact the person Mayhew had met, whom he had identified as “Valledy Tvanov.”

The name seemed off to Virakhovskaya, who is originally from St. Petersburg (formerly Leningrad). With the information she had, though, she searched for him. She also signed on to the Russian version of Facebook and informed people that members of the band were returning for a visit in 2012.

In St. Petersburg, Mayhew was able to see Valery Ivanov, the real name of the French horn player he’d met decades before. They hugged. Ivanov brought with him a signed piece of sheet music Mayhew had given him in 1961. On his lapel, he wore a University of Michigan pin.

Sources for the article include:

Symphony Band 1961 Tour collection, 1960-2023; Russian Tour Revisited: collected memories, letters, notes and diaries, 2008; Loren Mayhew diary, 1961; Jane Otteson King records, 1961; “A Talk with Paul Ganson and Dave Wolter,” circa 2011 (recording); William Revelli, “Reflections on a Musical Adventure,” parts I and II, SAGE Publications, 1961; “Revelli: The Long Note,” U-M Heritage Project, by Kim Clarke.