Magazine

Fields of Gold

One researcher’s quest to resurrect a nearly extinct strain of rye seed started in the archives but quickly expanded to seed banks, national parks, a whiskey distillery, and beyond. The improbable journey resurfaces a forgotten chapter of Michigan agricultural history.

by Lara Zielin

It was February 1921, and Frank Spragg was excited to talk about seeds.

Spragg, a professor of plant breeding at Michigan Agricultural College, had been invited by University of Michigan Professor H.H. Bartlett to the upcoming Academy of Science meeting.

Spragg’s archived reply enthusiastically accepted the invitation and offered Bartlett several subjects of interest upon which he could speak. Would Bartlett want a talk about producing seeds, registering seeds, and distributing seeds? If not, perhaps something about plant breeding? Or the mathematics of genetic plant expectations?

Spragg’s pioneering work at Michigan Agricultural College in East Lansing, now Michigan State University (MSU), meant he was an expert in all of it.

Maybe realizing that he was offering up a sizable array of options, Spragg wrote to Bartlett, “Perhaps I had best hear from you again before deciding on a subject.”

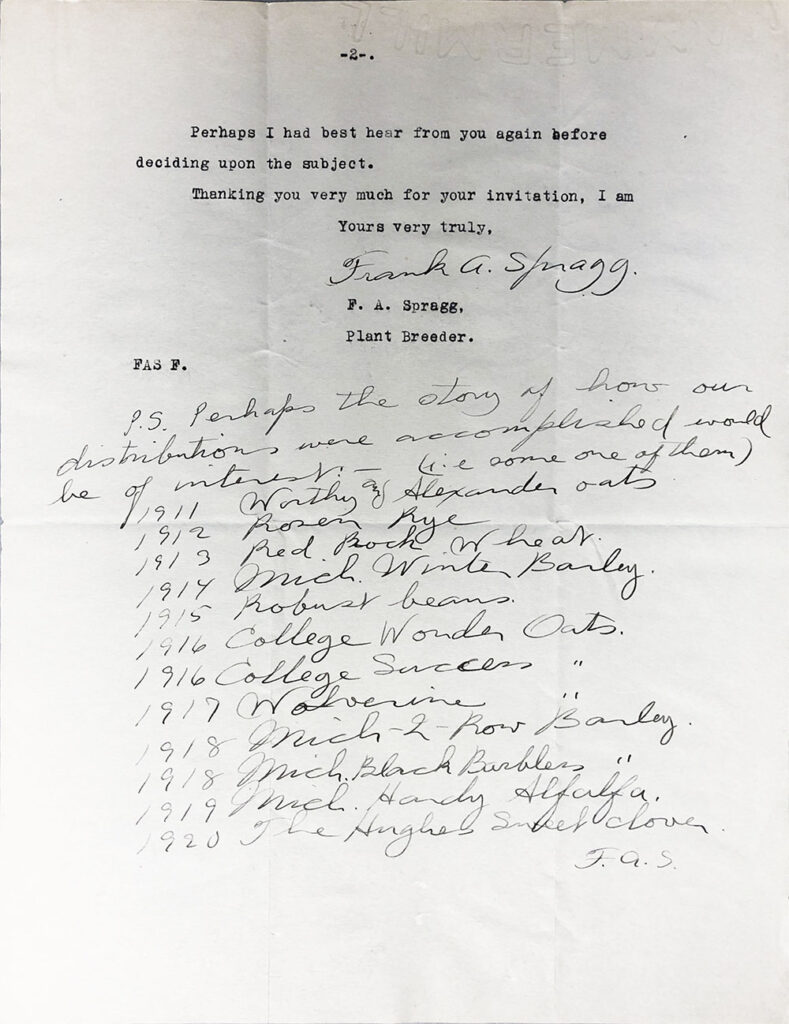

But then, as if he couldn’t help himself, he penned one more option at the bottom of the letter. “Perhaps a story of how our [seed] distributions were accomplished would be of interest.”

Spragg’s archived letter reveals a hand-written note about Rosen rye seeds.

And there, tucked into his hand-written list of 12 seed types, was the name of a seed that would become one of Spragg’s biggest successes. It would put Michigan on the map as an agricultural leader. And, years later, it would be an archived clue that a researcher named Ari Sussman would follow to revive the seed and once again enable it to thrive.

The story was right there in Spragg’s handwritten scrawl: A little seed called Rosen rye was about to change everything.

From Russia With Love

The story of Rosen rye begins well before Spragg’s talk—starting in Russia around 1894, when a young agricultural student at Moscow University named Joseph Rosen was flagged as a member of the Russian Social Democrat Party. The group was considered revolutionary, and Rosen was sentenced to exile in Siberia as punishment. But Rosen was able to escape to Germany, then to the United States in 1903. He found work on a farm for two years, then enrolled at Michigan Agricultural College.

That’s where his path crossed with Spragg in 1909. And Rosen came with ideas.

Specifically, Rosen had a hunch that parts of Michigan would be ideal for growing rye because of the state’s climate and light, sandy soils. Spragg agreed, so Rosen asked his father back in Russia to send him rye seeds. Spragg and Rosen planted the first rye crops, which produced “double the yields obtainable with any other variety,” according to one agricultural bulletin.

Spragg named the seed Rosen rye in his student’s honor, and farmers around the state clamored for seeds. The only difficulty was how easily the rye crops were cross-pollinated. Any gust of wind could pollinate the rye with an inferior crop, reducing the quality of the whole yield.

This was a disastrous turn and, by 1918, out of the 250,000 acres of Rosen rye in Michigan, “only a small amount [was] passing the regulations for certification,” wrote the Michigan State Board of Agriculture in its annual bulletin. “The community effort that has made this variety the standard for Michigan is praiseworthy, but an even greater community effort will be required to keep it pure.”

Spragg knew that he needed to find a way to isolate the rye crop to protect it. For this, he’d be on his own, since Rosen had left Michigan for work in Minnesota training agronomists on high-yield crops, then to New York where he headed up the agricultural office in the International Commercial Bank of Petrograd.

Spragg scoured the state for a location that could save Rosen rye from extinction. He found one in an unlikely place: an island surrounded by shipwrecks, where a hardy group of farmers were scraping out a living. He was about to change their futures.

Island Time

South Manitou Island is roughly 17 miles west of Leland, Michigan, in the cold waters of Lake Michigan. The island is approximately eight square miles, with a lighthouse on its southern tip, sand dunes along its western coast, and farms in the middle.

The farmers living on the island were mostly subsisting on what they grew. If there were extra quantities of fruits or grain crops, they were sold to steamboats on their way to big cities on the Great Lakes like Chicago or Buffalo. But Spragg saw the isolation of the island as a huge benefit—it would prevent cross-pollination and preserve the quality of Rosen rye. And the high yields of Rosen rye would mean the farmers could produce more crops, ideally earning more.

Spragg was convincing and, by 1919, the farmers on the island were exclusively planting Rosen rye. To keep the Rosen rye strains free from other pollinating seeds, all the farming families on the island made a pact—swearing under penalty of drowning—to raise only this rye.

“In perfect isolation of the island’s forest-surrounded fields, there has been produced some of the purest and best quality of rye known,” wrote Howard C. Rather in his 1925 bulletin Coming Through With Rye. “Island rye, resulting from this careful selection work, has won sweepstakes honors at the International Grain and Hay Show, the greatest distinction which rye can achieve.”

The South Manitou farmers became known as the “Rye Kings” and the island was the “World’s Rye Center.”

Soon, there was a high demand for these certified rye seeds in the U.S., namely by major whiskey-producing regions. The high-quality rye produced better, more flavorful whiskey. An advertisement for Old Schenley Rye called Rosen rye “the most compact and flavorful rye kernels that Mother Earth produces.”

The rye business boomed—even through Prohibition. The reputation of Michigan Rosen rye ensured that whiskey bootleggers along the East Coast and beyond continued to supply it and use it to make spirits.

Rosen rye had taken root in Michigan, but even so, its extinction was nigh.

Death and Resurrection

By the 1940s, the rigors of agricultural life had taken their toll on the farmers of South Manitou, and many were in bad health. Their children didn’t want to take on the labor-intensive work of farming rye, opting instead for life on the mainland with better jobs and larger communities. With their prospects diminishing, many of the farmers sold their land to a developer named William Boals, who began to introduce tourism to the island.

Coupled with the farming exodus on South Manitou was a shift in American drinking habits. Old, rich whiskeys were swapped for lighter spirits like vodka, which saw a 300 percent increase in sales from 1949 to 1950.

The last distiller to use Rosen rye was Mitcher’s in Pennsylvania, which ceased production in 1970. Frank Spragg was long dead—he’d been killed in a car accident in 1924—and Rosen had died in New York in 1949. Rosen rye and its history were vanishing.

Rosen rye might have disappeared entirely except for a researcher and whiskey distiller named Ari Sussman who, while poring through documents in an archive in Kentucky, stumbled upon a copy of the Old Schenley Rye ad—the one that said Rosen rye was the best that “Mother Earth produces.”

Sussman was intrigued. The ad specifically mentioned that Rosen rye was Michigan-grown. Sussman was born in Michigan and grew up in Ann Arbor. He’d attended Michigan State University and had managed MSU’s research and development distillery but had never heard of Rosen rye.

As the whiskey maker for Michigan-based Mammoth Distilling, Sussman wondered if Rosen rye was gone entirely. Were any seeds left anywhere and, if so, could they be grown—and turned into whiskey—once again?

Curious, he started diving into archives across Michigan, including the Bentley, looking at old seed catalogs, advertisements, and letters like the archived correspondence between Spragg and Bartlett.

“The Bentley was central to my early research and work,” Sussman says.

Ari Sussman first read about Rosen rye through an archived whiskey advertisement. He was able to obtain 18 grams of the original seed, which he’s now grown into enough rye to share with farmers and other distillers. Photo by Sandra Wong Geroux.

In the archives, Sussman began to put together the whole picture: of Rosen, Spragg, the “Rye Kings” of South Manitou Island, and the vanished seed.

Sussman and Mammoth Distilling founder Chad Munger talked to everyone they could think of to track down Rosen rye seeds—farmers, agricultural businesses, academics—but none of the leads were successful. Then, Eric Olson, the head of grain breeding at Michigan State University, contacted the federal seed bank and was able to obtain 18 grams, about a small handful.

This precious quantity was grown in isolated greenhouses and walk-in coolers at MSU, eventually producing enough rye for a foundation crop. But where to plant it? The same problem that had presented itself to Spragg and Rosen now presented itself to Sussman: If he wanted to keep the rye pure, he’d have to find somewhere that it couldn’t be cross-pollinated.

Like Spragg before him, Sussman turned his eyes to South Manitou Island.

Parks and Preservation

In 1961, Michigan Senator Phil Hart introduced two bills to establish the nation’s first national lakeshores: Pictured Rocks in the Upper Peninsula; and Sleeping Bear Dunes in the Lower Peninsula, the latter comprising 35 miles of Lake Michigan shoreline and both North and South Manitou Islands.

Hart, whose political platform was grounded in environmental and civil rights issues, fought for almost a decade to get the parks established. His archived papers at the Bentley show his tireless efforts— and his elation once the legislation was signed by President Richard Nixon.

“When people join together with their focus firmly on what the future requires, persistence and dedication succeed,” he wrote to Willard Wolfe of the West Michigan Environmental Action Council on October 28, 1970.

Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore was a boon for Michigan’s environment— not to mention its growing tourism industry—but it made Sussman’s quest to replant Rosen rye on the island all the more difficult. Was it even possible to plant crops on land owned by the National Park Service?

Sussman says that Mammoth Distilling invested heavily in the effort to resurrect Rosen rye, and that Mammoth ultimately was able to obtain a historical use permit for South Manitou. “We really believed there was value in the crop, and that it told an important story about Michigan,” Sussman says.

In the fall of 2020, the first modern crop of Rosen rye was planted on the island, “about the size of a horse blanket,” Sussman says.

The work was largely manual labor. “You can take tractors, but they have to be small enough to load onto a landing craft. Everything needs to be ferried. The weather has to be perfect because the lake is so treacherous there.”

Rosen rye on South Manitou Island. Photo by Maggie Kimberl.

Now, three years later, Sussman says Mammoth has enough Rosen rye to make whiskey and keep planting seeds. “We think it makes a full-flavored whiskey with a pedigree,” he says. “We want to make Rosen rye whiskey that honors our agricultural heritage, and that tells the story of Rosen, Spragg, and the South Manitou Island farmers.”

Distillers from across the world have contacted Mammoth about accessing the seeds for whiskey, Sussman says. And farmers want the seeds, too.

“Growing rye is great for the environment, and it can provide an alternative to corn and soybeans,” Sussman says. It’s hardier, combats soil erosion, grows when other plants don’t, and is beneficial for water filtration. “It’s worth the investment. It can be incredibly beneficial to agriculture in northern Michigan.”

For its part, the Michigan legislature seems to be taking notice. Recently, Michigan Senate Resolution Number 63 was passed, recognizing June 23 as “Rosen Rye Day.”

Sussman says none of this work would have been possible without archived records to point him in the right direction. “The Bentley is an amazing resource,” he says. “We have this heritage, and it’s a great story. It’s wonderful that it’s been preserved—and is now being recognized again.”

Sources for this story include:

University of Michigan Herbarium collection; Rather, Howard: Coming Through With Rye, Michigan State College of Agriculture and Applied Science, 1925. Williams, Alanen, Tishler: An Historic Agricultural Landscape Study of South Manitou Island at Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore, Michigan, National Park Service, 1996. Guide to the Papers of Joseph A. Rosen (1877-1949), Center for Jewish History. Jewish Telegraph Agency, Daily News Bulletin, April 3, 1949. Leelanau Ticker, August 22, 2022. Environmental Activism in Michigan online exhibition, Michigan in the World, 2017.