Magazine

How to Qualify as a Person

Forty-nine years before women were granted the right to vote in the United States, Nannette Gardner would cast her ballot in Detroit, making women’s history. By fighting tirelessly for women’s rights, she would begin to shake the foundations of power in the United States, and her controversial vote would give the suffrage movement a notable victory.

By Amy Probst

On a rainy April morning in 1871, Nannette Gardner headed to the voting precinct in Detroit’s Ninth Ward to vote in an election—some 49 years before the 19th Amendment would grant her that right. Gardner was about to make history, becoming one of the first women to cast a ballot in the state of Michigan. Handfuls of men gathered to watch, some mumbling under their breath. They’d never seen a woman vote like a man. Reactions ranged from amusement to fear that the Women’s Suffrage Movement would turn the country on its head.

Indeed, Gardner’s vote in the ballot box that day was a harbinger of things to come. Newspapers throughout the states reported the incident. Had she broken the law? Who let her get away with it? Would it happen again? And why had Gardner succeeded, when so many other women had been fighting for decades to vote?

The Cornerstone of an Argument

Born Nannette Ellingwood on October 27, 1828, Gardner was raised in an abolitionist family in New Hampshire. She grew up alongside the Underground Railroad, helping those fleeing slavery reach Canada. At age 26, she married Miles T. Gardner, a wealthy seedsman and nursery owner, which put her in a position to devote more means and time to both abolition and suffrage.

When Miles died in 1867, he left Gardner with two children, Sarah and Miles Jr., and a great deal of land and business to manage—and pay taxes on. This would become the cornerstone of her successful argument for the vote.

The U.S. Constitution guaranteed equal rights for all citizens, with all persons being equal. But determining who qualified as “citizens” and “persons” was left to each state. And in 1871, the states were largely in agreement that a citizen was a taxpaying landowner, which excluded women.

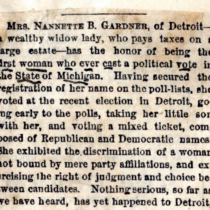

Gardner, photographed here in 1871, argued she was a widow paying taxes without representation and should be allowed to vote.

But, as a widowed taxpayer, Nannette argued that the Constitution’s right to vote applied to her, too.

In March 1871, Gardner and Catharine Stebbins, a lifelong activist and close friend, hopped a carriage to City Hall in Detroit and completed applications to have their names added to the voter rolls in their respective wards. This was a required first step, as only registered voters received ballots to deposit on election day.

When the all-male board of inspectors for the Ninth Ward learned that a woman had registered her name to vote, a motion was made to have Gardner’s name immediately erased from the registry. Stebbins’s registration received the same motion. Both Gardner and Stebbins scheduled erasure hearings in their respective wards.

The Hearings

At their hearings, both women contended that, according to the language of the First and 14th Amendments, they qualified as actual persons—citizens and inhabitants of the country—and therefore had right to a vote. Unfortunately, the newly adopted 14th Amendment included troubling language for women, introducing the word “male” into the Constitution to qualify both “inhabitant” and “citizen.”

Gardner and Stebbins represented themselves at their hearings, as opposed to hiring a male attorney to argue their case. They argued with eloquence and approached their respective boards as equals.

Stebbins’s motion was denied on the basis that she had a husband who could vote on behalf of her interests, and the board of registration redacted her name from the ward’s voter roll.

Gardner’s hearing went differently, thanks in equal part to her well-reasoned logic, affable demeanor, and a man named Peter Hill. Having been widowed, Gardner explained, she was now paying taxes without representation. Enrolling officer Hill agreed with her.

The board voted down the motion to remove her name from the rolls, 12–6.

Outraged and undeterred, the six overruled men made a second motion, this time asking their fellow board members to reconsider, come to their senses, and please erase Gardner’s name once and for all. This second motion was “laid on the table,” meaning it wasn’t even considered for debate. This meant Gardner was officially registered to vote.

The Vote

Gardner’s daughter, Sarah, was 12 years old in 1871 when her mother voted for the first time. She kept a journal that is preserved at the Bentley Historical Library, and in it she describes the spring day that changed Michigan history.

“April 3: This morning ma went to the polls in the 9th Ward and voted. Mr. Smith, Mr. Stebbins . . . and myself went first. The carriage returned and took ma, Mrs. Stebbins, Mrs. Starring and Millie. After ma had deposited her vote she presented Mr. Hill a beautiful bouquet which was placed on the table near the ballot box.”

The bouquet for Hill included a banner of gold-trimmed white satin, on which was inscribed: “To Peter Hill, Alderman of the Ninth Ward, Detroit. By recognizing civil liberty and equality for woman, he has placed the last and brightest jewel on the brow of Michigan.”

Just a few days after the vote, Sarah’s journal also notes the arrival of an important visitor:

“Friday, April 14: Susan B. Anthony stopped by here last night on her way to St. Clair and is coming back tomorrow.”

“Friday, April 16: Mrs. Anthony came back yesterday and will remain here until tomorrow. She said that she could not rest contented until she had slept under the roof of the house of the first woman that had voted under the 14th and 1st Amendments.”

Gardner’s vote made headlines in papers throughout United States, and Gardner herself wrote letters to the press about her experience and opinions.

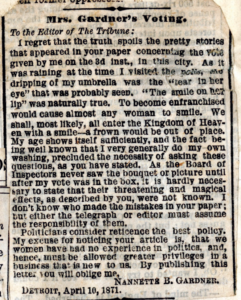

Gardner published her own editorial to correct the details that newspapers got wrong about her historic vote.

“It is difficult for me to appreciate that so simple an event as a woman expressing a choice among a few candidates for office should have caused such a commotion and made me ‘suddenly famous,’” she wrote to the Detroit Post on June 3, 1871. “Tens of thousands of vicious, ignorant, and worthless men do the same thing yearly without a word of comment.

“When woman’s power becomes effective, the keystone of that arch that now sustains the wily politician’s structure will be knocked from its resting-place, and the whole will tumble into a pile of splendid fragments.”

She also wrote to the Detroit Tribune to correct that paper’s flowery account of her vote. “I regret that the truth spoils the pretty stories that appeared in your paper,” she said. “As it was raining at the time I visited the polls, the dripping of my umbrella was the ‘tear in her eye’ that was probably seen. ‘The smile on her lip’ was naturally true. To become enfranchised would cause almost any woman to smile.”

In addition to newspapers, she also corresponded with women from around the country. Marie Rowland, Woman’s Club President in New Jersey, read of the vote in the New York World and immediately penned a letter to Gardner. “Will you be so gracious as to write me and tell me if that account is true or simply a newspaper hoax?” she asked. “If it is true that your vote was legally tendered and accepted it is a most important fact to the women of the country.” Today, Rowland’s letter is archived in Gardner’s collection.

Honoring the Helpers

Gardner recognized Alderman Peter Hill for the role he played in her initial vote, and for his decency and pivotal role in women’s suffrage. After Gardner voted again in 1872, she wrote that Hill deserved the honor of “being the first officer of registration who has given suffrage to woman. . . . And in taking the lead in this grand movement, Mr. Hill will become a mountain among his peers for being the first to act as Woman’s Emancipator.”

Hill was also honored by the Detroit Equal-Suffrage Association with a resolution upon his passing in 1893. A note handwritten by Gardner details the resolution as “honoring with reverence and love” the memory of Hill and his humanity “to receive and record the vote of a Woman-citizen under the 14th Amendment.”

After an 1874 election, Gardner also wrote a public card of thanks “to the gentlemanly policemen” who’d served at the Ninth Ward. Presumably, they’d kept order, even when Gardner once again cast her controversial ballot. “Every policeman, without exception, was quiet, vigilant, considerate and respectful.”

Gardner continued to fight for women’s rights, developing friendships along the way with Susan B. Anthony and Sojourner Truth.

In her collection is a lecture poster with bold headlines of “Woman Suffrage!” and “Political & Moral Reforms.” The lecturer was George B. Smith, a widower dedicated to Gardner’s same causes.

Sarah’s journal documents that the lecture was not the last they’d see of Smith:

“Wednesday, June 14: Mr. Smith got us a beautiful double petunia at the market.”

Gardner and Smith fell in love and married in February 1873 in his hometown of Granville, Ohio, then settled in Detroit. Sadly, Smith died the following year.

After Smith’s death, Gardner moved to Hillsdale, Michigan, for her children’s education, then to Alabaster, Michigan, where she had an interest in a lucrative plaster quarry with brother-in-law Benjamin Smith. In 1881, her son, 19-year-old Miles Jr.—“a manly boy; modest, affable, and courteous”—died of “a wasting disease,” as reported in the Hillsdale Democrat.

Gardner and daughter Sarah eventually settled in Ann Arbor, building homes at 75 Washtenaw Avenue and 1221 Willard Street, sites of a Lutheran Church and parking structure today.

Gardner remained an influential personality in the suffrage movement throughout her life, remembered by peers Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton in Volume 3 of their History of Woman Suffrage. Sarah, who would become an accomplished artist, created a bust in tribute of her 70-year-old mother, and a photo of the sculpture resides in Gardner’s collection.

Gardner died in 1900 at age 71. In 1920, the 19th Amendment was ratified, granting women the right to vote.

[Lead image: An undated newspaper article in Gardner’s collection documents her historic vote]

Sources for this story include:

Bentley collections including the Nannette B. E. Gardner papers and the Nannette Brown Ellingwood Gardner photograph series. Henry Laste: Biographical sketch of Nannette E. G. Smith from the National American Woman Suffrage Association. The 19th Amendment exhibit, National Archives and Records Administration (May 14, 2020). Catharine F. Stebbins: “The True Believer,” the 100 Signers Project. Mary Ellen Snodgrass: The Underground Railroad: An Encyclopedia of People, Places, and Operations (M.E. Sharp, 2008). Dana Elizabeth Weiner: Race and Rights: Fighting Slavery and Prejudice in the Old Northwest, 1830–1870 (Cornell University Press, 2013). Frank B. and Arthur M. Woodford: All Our Yesterdays: A Brief History of Detroit (Wayne State University Press, 1969). Carnegie Corporation of New York: Voting Rights: A Short History.