Magazine

In Defense of Nature

Before Earth Day and the Clean Water Act, before the protection of Sleeping Bear Dunes and Isle Royale, there were Michigan citizens fighting for the environmental health of the state. Collections at the Bentley reveal how Michigan went from overwhelming natural abundance to an environmental wasteland — and how some unlikely people helped bring it back.

by Robert Havey

The settlers who came to the Michigan Territory during the beginning of the 19th century weren’t thinking about how their actions were going to forever impact the environment. They found themselves in a land with rivers and lakes teeming with trout and grayling, acres of virgin pine forest filled with wild game, and few other people to share it with. There were around 10,000 people including the American Indian tribes in Michigan in 1800. A Michigan settler’s main concern was about how they could protect themselves from nature, not so much the other way around.

Michigan’s population exploded after the completion of the Erie Canal in 1825 and several new railroad lines in 1836, connecting the territory to the expansion-hungry eastern states. The territorial government, and later the new state government, were selling off parcels of land as fast as they could, much of it obtained through unfair treaties hastily signed with American Indian tribes.

What happened next was an environmental catastrophe on a scale difficult to imagine today. Michigan’s vast acres of old growth pine forests were sold to logging companies on the cheap. There were few laws in place to regulate harvesting methods and no enforcement. William N. Sparhawk, Forest Economist for the U.S. Department of Agriculture, wrote in 1929 that “In less than 100 years” of Michigan statehood, “nearly 33,000,000 acres, or 92 percent, of [Michigan’s] original forest has been cut or destroyed.”

During the lumber rush of the 1800s, forests that took centuries to grow were cut down so fast and so haphazardly, with the fields of tree stumps so choked with sawdust, that giant spontaneous wildfires became common. Sparhawk wrote, “The little [forest] left has been wiped out over wide areas by conflagrations, the destructiveness of which has been intensified by the huge masses of logging debris.” He also noted that the frequent fires ruined any chance for any forests to recover. “If per – chance a tree or a group of young growth escaped the first fire, it was licked up sooner or later by another.”

The commercial fishing industry was experiencing a similar level of harvesting with consequences just as dire. Scores of fishermen dragged densely woven nets through lakes and rivers, catching huge numbers of grayling and trout. The nets also captured many fish too small or too mangled to sell. While the best of the catch was packed in barrels and shipped around the country, the castoff fish would simply be wasted. There were reports of fish piled on riverbanks, left to putrefy in the sun while the poison runoff would eventually bleed back into the water.

A Huntsman’s Rebuttal

Some of the first people to observe and object to the waste and destruction were Michigan’s recreational outdoorsmen. During their trips into what remained of the Michigan wilderness, these hunters and fishermen saw firsthand their quarry and cover disappear. William Butts Mershon, whose papers have been recently digitized by the Bentley, after fondly recounting his first deer hunting trip to the Au Gres River, lamented, “All these localities I have mentioned are now with – out a tree large enough to make a saw log. What the lumberman did not get, the forest fire destroyed.”

An outdoor biology lab circa 1933. HS18779

Mershon, with other Michigan outdoorsmen his age, inherited the tradition of hunting and fishing from a generation who relied on those skills for survival. Hunting was a rite of passage, it was proof of self-reliance. Although he and his family owned logging operations in Saginaw, Mershon believed that “the State should purchase large areas and set them aside forever for the people who enjoy the grand, health-giving, mind-purifying sport with rod and gun.”

Mershon saw the diminishing of the game he hunted as a boy not as a problem of over-hunting, but of habitat destruction. “Environment, and not the gun of the sportsman, must be the explanation,” he wrote in his 1907 book, The Passenger Pigeon, about hunting the extinct bird. The areas of Michigan that were once unreachable by hunters and loggers, where populations of game could recover, were gone.

“When the forests were lumbered, burned and cleared for the farm, when the lakes and marshes were diked and drained, when roads and Fords both came to the trout nursery in the cedar swamp, when the rail fence gave way to the barb wire, then there had to be a change in what inhabited these regions.”

Perfectly Appalling

Four decades after it became a state, the Michigan government finally started to take action to protect its natural resources. The first Michigan Fish Commission was established in 1873, monitoring fish populations and setting up the first state fish hatchery. After much lobbying by Mershon and the Michigan Sportsman Association, the state appointed a game warden in 1887, who was in charge of enforcing the state hunting laws. The Michigan Forestry Com – mission was founded in 1899.

Citizen groups dedicated to protecting parts of the environment flourished in the early 1900s. Michigan’s chapter of the Audubon Society, a bird conservation group, formed in 1904. Their mission, in part, was to “disseminate information respecting the economic value of birds” and “their importance to the welfare of man.” Their lobbying efforts aimed to save more bird species from the fate of the passenger pigeon and prairie chicken.

A Michigan Conservation Officer displays deceased oil-soaked ducks from the Detroit River, 1951. HS 11582

Advances in conservation came in two types: political and scientific. Lawmakers’ decisions on things like the date when a hunting season started and ended, or if a section of forest could be cut down for lumber, depended on knowing the impact those decisions would have on the environment. And that required reliable scientific knowledge. Such science was hard to come by during Michigan’s first attempt at conservation policy. When working to set up the state fish hatchery in 1873, the Michigan Fish Commission reported, “[T]he ignorance on the subject was perfectly appalling. It seemed as if natural history and natural science stopped at the water’s edge.”

The University of Michigan was the first in the country to offer regular courses in forestry in 1881. The Department of Forestry was created in 1903, later becoming the School of Natural Resources, then the School of Natural Resources and Environment, and is today known as the School for Environment and Sustainability. Early for – estry classes were designed to teach ways that trees could be sustainably grown, maintained, and harvested for human use. This was accomplished in part with “field day” trips to the Saginaw Forest where students could learn in nature.

Platforms and Movements

World War II profoundly affected America’s relationship with industry and the environment. The post-war prosperity meant that people had time and money for lei – sure. Public nature parks were popular, and their protection became a priority for many Americans.

The way news and information about the environment was shared also went through radical changes during this time.

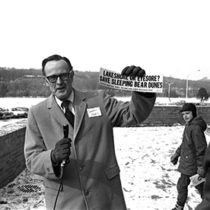

A sign on the Detroit River in 1948. HS4604

Jack Van Coevering was the popular outdoor editor for the Detroit Free Press. He wrote columns about hunting and fishing almost exclusively for the first two decades of his career, but in the late 1940s he started writing stories about pollution in the Detroit River. Like Mershon, Van Coevering stumbled upon the ugly byproducts of Michigan industry. Unlike Mershon, he had photos and a platform to show the world.

Van Coevering covered stories on environmental topics including pesticides, oil spills, and flood control. He joined the staff of U-M’s School of Natural Resources in 1967, doing research and teaching classes on many topics, including environmental communication. In his later years, Van Coevering wrote a history of the conservation movement in Michigan, a manuscript copy of which resides in his collection at the Bentley.

In the 1960s, the rise of the environmentalism movement drew the modern political battle lines we are familiar with today. This history, including U-M’s role in the first Earth Day, can also be found in Bentley collections.

Natural Selection

The Bentley Historical Library has numerous collections that document the history of conservation and environmentalism in Michigan.

This collection contains diaries, correspondence, and photographs of the famous Saginaw lumber baron, hunter, and conservationist. A large portion of the collection has been recently digitized and is available online.

Van Coevering was a longtime nature editor for the Detroit Free Press and later lectured at U-M. His collection contains clippings of articles over his 35-year career and a completed manuscript on the history of conservation in Michigan.

School for Environment and Sustainability (U-M) Records

The administrative files and photographs from this collection reflect the academic approach to conservation since 1903. There is material pertaining to classroom activities and field research.

Michigan Audubon Society Records

Michigan’s chapter of the national bird protection society formed in 1904. The collection represents its history of advocacy and its organization of conservationist causes.

Michigan United Conservation Club Records

In 1937, the MUCC was formed to bring together the many local clubs that were interested in conservation. The organization has advised the state legislature on conservation legislation and has led education outreach efforts to raise public awareness of conservation issues.

Milliken was a women’s rights activist and environmentalist. Her collection spans her time as the first lady of Michigan and contains photographs, speeches, and correspondence relating to her advocacy of billboard control, bans on disposable bottles, and opposition to oil drilling in Pigeon River State Forest.