Magazine

In the Footsteps of Hobbs

by Madeleine Bradford

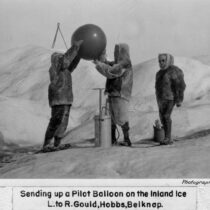

[Lead image: U-M Professor William Hobbs and his team release a weather balloon in the Arctic in 1926.]

Two words flicker on-screen: “The Ascent.” An Arctic landscape, entirely black and white, surrounds a man holding an enormous balloon over his head.

He lets go.

The balloon twirls quickly away, swept into the sky over Greenland. The next film clip shows the 1926 U-M expedition team tracking the balloon through the air. Led by Professor William Herbert Hobbs, this was the first of three U-M trips to Greenland between 1926-1928, to study the polar winds.

“Some of the first measurements of the weather in Greenland were done by Hobbs and his team,” says U-M Professor Perry Samson. A weather expert himself, Samson felt driven to carry this legacy forward. In 2006, together with Professor Bob Clauer, he crafted a plan.

With a team of undergraduates, they would follow Hobbs’ path to the Arctic. Those students would see firsthand just how critical Greenland is to the study of climate change and the Earth’s atmosphere.

In a C-130 aircraft with a bone-rattling engine, their team of professors and students descended towards Greenland. Rivers of glacial meltwater unfurled below.

According to Samson, as that meltwater flows into the sea, the diluted seawater also affects how greenhouse gases are taken out of the air, worsening the rise of carbon dioxide in our atmosphere. The global impacts are serious: sea levels climb, and storm paths across America and Europe threaten to shift. NASA’s data shows that, between 1992 and 2018, Greenland lost 3.8 trillion tons of ice—and it’s only melting faster.

Tracking how much sunlight Greenland’s ice absorbs, and the flow of its rivers, Samson and Clauer hoped to show students symptoms of earth’s quickly shifting climate. Following Hobbs’ journeys, they also hoped to show students where they stood in scientific history.

Enter Exploring About the North Pole of the Winds, Hobbs’ book on his adventures. Discovered in the Bentley Historical Library by one of Samson’s students, and also available online, this volume helped them imagine the difficulties of early research.

Students crunched across the icy landscapes shown in its pages. Using both modern and historical tools, they recreated Hobbs’ own experiments. With their own “theodolites,” telescope-like devices used to measure angles, students tracked balloons through arctic wind currents—easy enough, with modern, automated versions.

Historical theodolites, however, needed careful balancing, with measurements taken by hand. The process proved frustratingly delicate.

“Connecting the history and what [Hobbs’ teams] did with what the students were doing gave them some good appreciation,” Samson says. Using scanned photographs, film, and documents from the Bentley’s collections, he helped students link past research directly to their present.

Part of learning Hobbs’ history also meant seeing what not to repeat. The 1920’s expeditions hired local Greenlanders, but demanded a great deal of labor for little respect. The teams were otherwise entirely composed of white men.

“Expanding the field and making it more inclusive for a wider range of students,” is a responsibility to take seriously, Samson says, himself a first generation student whose career was inspired by experiential learning.

To underline that science isn’t divorced from its human impact, students also learned about the culture and history of the area. Watching a presentation on the nearby UNESCO site, and meeting a local ranger (and her huskies), students learned how climate change affects people in Greenland, from local Greenlanders. They had the chance to try musk-ox stew, and attend Greenland’s self-government celebration. They also left a device behind, to track future pollution.

The trip had lasting effects; several students went on to environmentally focused graduate careers.

In 2019, Samson brought another team, alongside Professors Clauer, Mark Flanner, and Jeremy Bassis, and used drones to capture the crumbling ruins of Hobbs’ Weather Observatory, and the nearby Russell Glacier, in 3-D.

The 2019 Greenland undergraduate research expedition, led by U-M Professor Perry Samson.

One night, a chunk of ice the size of half of U-M’s Graduate Library cracked off of that very glacier; a stark example of climate change in action.

The ice plummeted to the water below.

The students took pictures before, and after. Their 3-D tour of the glacier—something Hobbs likely never imagined—is part of a free online course titled “Melting Ice, Rising Seas,” sharing climate change’s realities with everyone.

Professor Samson intends for materials about these trips to live at the Bentley Historical Library. “It seemed appropriate,” he says, considering the long history of Michigan’s research in Greenland. Samson hopes they’ll go back.

“We’re actually in the process of writing a new proposal to do this annually,” Samson says. He hopes new students and faculty can keep learning about this past, all the better to help them understand the present, and investigate the future, of the planet.