Magazine

It Was a Man’s World

The early 1970s were pivotal years for women’s equality at Michigan. Government pressure was mounting for U-M to give women a level playing field on campus, but the University’s all-male administration was slow to act. Papers at the Bentley reveal how a group of determined women demanded accountability and action.

by Lara Zielin

In October 1970, as campus trees turned vibrant with fall color, the University of Michigan prepared to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the admission of women. The events from October 10-11 included workshops, panel discussions, a bazaar to distribute information on local women’s groups, and a teach-in titled “The Changing Roles of Women in the U.S.”

As the events progressed, what no one in attendance knew was that just days prior, on October 6, the federal government had filed a complaint with the University of Michigan alleging U-M discriminated against its women employees. The complaint, written by the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (HEW), was 12 pages long with statistical evidence and exhibits to back up its allegations. It included strict demands that the University fix its ways within 30 days or risk losing federal funding.

As women at the nearby centennial events distributed their own data showcasing women’s low standing in salary and rank at the University, U-M President Robben Fleming asked HEW for more time to review the complaint. While he promised he’d look into things, he wasn’t at all confident that there was actually a problem.

And he wasn’t alone. Male colleagues who reviewed HEW’s data wrote a scathing memo saying any findings were based on “inaccurate and incomplete information” and challenged HEW to find “concrete examples” of women who had experienced discrimination.

U-M had been given 30 days. But it would take much longer than that for the enactment of high-level administrative changes that benefited women directly.

Documents at the Bentley reveal how the early 1970s were pivotal years for women’s equality at Michigan. The University’s all-male administration was slow to acknowledge any failings, even in the face of government pressure. But a group of determined women demanded accountability and action—and wouldn’t take no for an answer.

“Prevents a Woman from Using Her Education”

To President Fleming and many of the University’s male faculty, the HEW complaint may have reached far-fetched conclusions, but the women who had initiated the HEW investigation had been living the complaint’s reality for years.

The Ann Arbor Focus on Equal Employment for Women, or FOCUS for short, was a group of women who had started gathering at the home of Ann Arbor lawyer Jean Ledwith King in early 1970. They traded stories of unequal treatment, unfair pay, lack of promotion, and more.

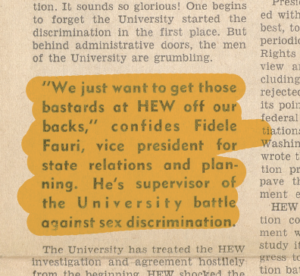

Daniel Zwerdling’s piece on sex discrimination in The Michigan Daily revealed how the highest levels of U-M’s leadership rejected the idea of inequality between the sexes on campus.

Like Helen Tanner, a U-M graduate with a Ph.D. in history, who had hoped to join the faculty as part of the Residential College. U-M had hired her to teach graduate students off campus, and she’d willingly shouldered the responsibilities of a full professor during a one-semester emergency. But in 1968, the department had rejected her appointment as a full professor.

At the time, according to data from The Michigan Daily, 13 percent of U-M Ph.D. degrees were earned by women, but only 7 percent of U-M’s faculty were women. An undergraduate receiving a four-year education was likely to encounter only two women professors that whole time.

“It seems clear that the U of M has become much more liberal in assisting women to acquire an education, but the present university system in Ann Arbor prevents a woman from using her education on this campus,” Tanner wrote.

King was among the first to realize that one way to force U-M to change its discriminatory ways might be new regulations from the highest levels of

government. An executive order signed by President Johnson in 1967 made it illegal for government contractors and the federal workforce to discriminate based on sex—including educational institutions like U-M.

King understood the powerful leverage the order gave them: U-M would need to address sex discrimination or risk losing millions of dollars in federal funding.

FOCUS drafted a two-page letter that outlined their case. In an interview many years later, King could still recall the long list of discriminatory practices: “[W]e cited the lack of women faculty (including none in the Law School and, as I recall, none in the Medical School), the low salaries of women faculty, the failure to hire and to promote women faculty . . .” The list went on.

King’s legal savvy—plus FOCUS’s connections to members of the government and media—meant the letter garnered attention quickly. Federal investigators were on campus within three months (“really the speed of light in federal investigations,” King recalled) and began talking to U-M officials, as well as Tanner and others.

Damning Results

Esther Lardent, one of the HEW investigators, was appalled by what she discovered at U-M.

In an interview 40 years later, Lardent says, “There was one comment in a file about a very distinguished woman . . . and her husband had accepted an appointment at Michigan, and in the file it said, ‘and we are very lucky because she’s following her husband, so we can pay her a lot less than we’d have to if she were a man.’”

Lardent continues, “I don’t think any of us sort of realized how intense this was, how accepted it was, how widespread it was. Women were clearly not taken seriously. They were not viewed as peers.”

HEW’s subsequent complaint, sent to U-M that October as the women’s centennial was in full-swing, included four specific allegations:

- Wage discrepancies existed between men and women in academic positions.

- Sex discrimination also persisted in non-academic employment practices.

- The hiring of women for faculty positions lagged behind the proportion of women who had earned doctorates.

- The admission of women to doctoral programs lagged behind the proportion of women earning master’s degrees.

HEW specifically cited U-M for being in violation of federal laws, and threatened the removal of federal contracts unless it provided a “written commitment to stop the discriminatory treatment of women” as well as detailed plans to take action in 30 days.

King had been right. The executive order had given them the leverage they needed. Now the question was: Would U-M do anything?

Extraordinarily Difficult Problems

When he responded to the HEW complaint, Fleming didn’t argue that discrimination on the basis of sex was wrong, but he did question whether it was actually happening.

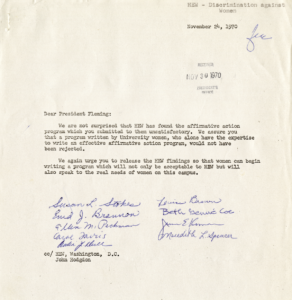

For months, U-M refused to make public the federal government’s findings showing that Michigan discriminated against women, despite letters like this one asking for more transparency.

Just a few months prior to the HEW findings, in the spring of 1970, President Fleming had negotiated with Black Action Movement members who had shut down the campus in a demand to increase minority enrollment at U-M, among other concerns. Fleming had been able to broker a resolution to get the campus back up and running again.

While Fleming was more than willing to admit that U-M had an issue giving fair and equal access to minorities, women were a wholly separate, and questionable, issue.

“There are extraordinarily difficult problems in establishing criteria for what constitutes equal treatment,” Fleming wrote to HEW, “and we believe they are quite different from the now familiar problems in the field of race.”

What’s more, even if there was a problem, Fleming told HEW that fixing the issue in 30 days was out of the question. He needed more time to develop any kind of affirmative action program.

HEW, however, held firm.

Don Scott, the HEW representative communicating with U-M, refused to accept Fleming’s complaints about the 30-day timetable and noted that federal funds were already on the chopping block—specifically, the renewal of a $400,000 contract between U-M’s Center for Population Planning and the U.S. Agency for International Development to provide family planning services in Nepal.

Fleming wrote back four days later, fuming that the 30 days hadn’t elapsed but that Scott was already cutting off funding. “We find this a capricious act,” he wrote.

Fleming underscored U-M’s position that “the evidence does not support the suggestion that there has been discrimination,” though he agreed to make changes to existing U-M programs. This included including establishing a Commission on Women, adding women to U-M committees where they weren’t currently represented, and including women in more centralized grievance procedures.

Negotiations ensued. U-M needed a comprehensive affirmative action plan that would put the University in compliance with federal regulations. HEW needed to make a strong example of Michigan as complaints rolled in about sex discrimination at other universities.

A U-M representative flew to Washington, D.C., on December 21, and on Christmas Eve, negotiations were settled. The Michigan Daily headline on January 4 read, “HEW Accepts U Proposals to End Sex Bias in Employment.” The Detroit Free Press declared, “U-M Sex Bias Plan Historic.”

U-M became the first university in the nation to establish an affirmative action plan to ensure equity between the sexes.

But change would come slowly—and for some, not at all.

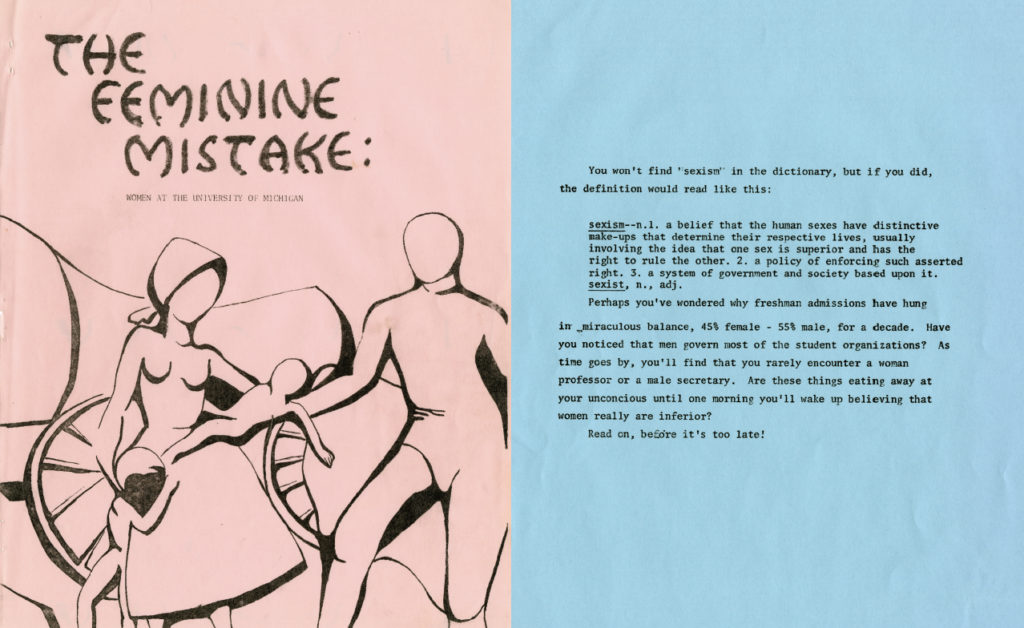

The Feminine Mistake, published circa 1970, features data and testimonials from the campus group PROBE about gender discrimination, including U-M’s quota policy for admitting fewer qualified females.

Abrasive Personalities

In 1967, astronomers Anne Cowley and her husband, Charles, moved from the Chicago to Ann Arbor under the impression that they would both be offered faculty positions at U-M. However, when they arrived, Anne was given a job as a research associate and told that she would have to obtain grants to support her work.

By the fall of 1969, there was vocal opposition from male faculty to any notion that Anne would ever be appointed to the faculty of the Department of Astronomy. As Charles was being considered for tenure, the department published an anti-nepotism policy, which ensured only one member of a family could serve in a professional capacity.

HEW’s findings just a few short months later concluded that anti-nepotism policies such as these contributed to sex discrimination. As the University began to implement affirmative action standards, the department reversed its anti-nepotism policy and, by 1971, Anne’s name was again floated for a faculty appointment. The department took a vote and rejected her 9-1.

Anne was no stranger to sex discrimination. At one point in her career, she said that the president of the American Astronomical Society sexually assaulted her in an elevator. “I never dared to complain since he had a huge amount of power over me and could have ended my career,” she later recalled.

After the HEW report was released and the Commission on Women established, Anne submitted formal complaints about her treatment—specifically her faculty appointment and her salary. The Commission on Women agreed her complaint had merit, but the Department of Astronomy wouldn’t budge.

When she appealed again, a three-person, all-male Complaint Appeals Committee heard her case and sided with the department citing, in part, feelings that her “personality was abrasive and her presence in the Department was divisive.”

Fleming ratified the decision.

It would take nearly a decade before U-M would offer Anne a position as full professor. But it came too late.

In 1983, Anne was part of an international research team that made a breakthrough discovery confirming the existence of multiple black holes in space. She was heralded for the findings and accepted a position at Arizona State University, where she is now a professor emerita.

In 1984, Cowley told the Daily, “I think the situation at the University of Michigan is scandalous,” and that efforts to increase the number of women faculty members were like “beating your head against the wall because the administration doesn’t care.”

Documenting Change

The most comprehensive chronicle of this era at Michigan is a book by U-M alumna Sara Fitzgerald titled Conquering Heroines: How Women Fought Sex Bias at Michigan and Paved the Way for Title IX (University of Michigan Press, 2020).

Fitzgerald was the first female editor of The Michigan Daily and was on campus when the HEW complaint was released. She recalls knowing this was a big moment for the University, and that the story wasn’t going to end any time soon. “We had a sense of needing to train younger reporters to understand this story so that once we graduated, people wouldn’t lose interest. I think it was a big deal to me because there was so much going on with the women’s movement in the 1970s. It was an empowering time to come out of college and feel like the world was changing.”

Over her career, Fitzgerald worked for the Washington Post and helped start a consulting company. Conquering Heroines was released in 2020—marking the 50-year anniversary of the HEW complaint and the 150-year anniversary of the admission of women to campus.

Fitzgerald drew on multiple Bentley resources for her book, including departmental records, recorded oral histories with women leaders during this time such as Jean King, as well as an oral history with President Fleming. Fleming’s own records of this time are preserved in his presidential papers, and the campus’s reactions to events are preserved in the now-digitized Michigan Daily.

“I wanted to understand how all this was playing out in the different corners of the University,” Fitzgerald says. “I wanted to explore new avenues and answer questions we hadn’t been able to answer in the ’70s.” For example, she looked at what conversations were taking place at the highest levels of leadership, or how frightened Michigan administrators were about the possibility that their federal contracts could be held up.

Fitzgerald ends the book with data about how much work is still left to be done. At U-M, the proportion of women who are faculty chairs has gone down in recent years. For the 2017–2018 academic year, the average salary of a male full professor was $173,046 compared with $160,271 for a woman. For lecturers, women at U-M make 80 percent of what their male counterparts do, “the approximate pay gap between men and women generally in the United States,” Fitzgerald notes.

“Part of the reason I wrote the book is to remind young women that it wasn’t so long ago that these things were happening,” Fitzgerald says. “There’s concern that women don’t think these are problems anymore.”

Sources

Sources used for this story include Conquering Heroines: How Women Fought Sex Bias at Michigan and Paved the Way for Title IX by Sara Fitzgerald, as well as several Bentley collections including U-M presidential papers (specifically President Fleming’s dedicated HEW folder), Regents’ proceedings, oral histories from the Academic Women’s Caucus, and Eric A. Stein’s recorded interviews for his graduate work titled Women’s Activism Against Sex Discrimination: The 1970 HEW Investigation of the University of Michigan. Online resources include the digitized Michigan Daily as well as documents and commentary compiled by Sara Fitzgerald titled “What Factors Led to the Success of the Historic 1970 Sex Discrimination Complaint Filed against the University of Michigan?”