Magazine

Living with Pride

During a time when many people stayed in the closet, Ruth Ellis — born in 1899 — forged a path for people in Detroit’s LGBTQ+ community, especially other African Americans, until her death at age 101.

by Katie Vloet

The cover of the journal makes a promise: “Secrets,” it declares, in shiny script against a background of cheery hydrangeas and roses. Tantalizing! What secrets could these pages hold?“After getting up this morning and had [sic] my breakfast. . . .” A trip to Target. A bowl of broccoli soup. A new TV, the need for a larger TV stand.

Hmm. Where are the secrets? Maybe in the later pages. Alas, flipping through until the end reveals that most of the pages are blank. But the absence of intrigue in this journal makes sense, in a way. Ruth Ellis received it as a present for her 98th birthday, and, by then, she had no secrets left to tell.

The center in Detroit that bears her name describes her as “one of Detroit’s oldest and proudest African American lesbians.” Born in 1899, she came out in 1915, according to some biographies. Ellis herself said she was never in the closet to begin with.

“I never thought about hiding who I was,” she said in a 1999 interview. “I guess I didn’t go around telling everybody I was a lesbian, but I wasn’t lying about it either. If anyone asked me, I’d tell them the truth, but it wasn’t the sort of thing people talked about much.”

Her collection at the Bentley Historical Library is also open— to researchers, to historians, to students, and anyone who wants to learn more about her story. It contains photographs, letters, and journals that paint a picture of a woman who changed lives simply by being herself.

THE GAY SPOT

Ellis’s early years in Springfield, Illinois, were filled with music. She could play the piano by ear, and she and family members loved to dance. But Ellis was also lonely. She was one of the few African American students in her class, and she became the only woman in her home during her teen years when her mother died. The racial divide was evident in the school population, but more violently during the 1908 Springfield Riots. Ellis recalled her father and brothers preparing for their home to be attacked, lining up the only weapons they had: a Knights of Pythias commemorative sword and a row of bricks, she recalled in her biographical notes.

During her teenage years, Ellis first recognized her attraction to women when she fell in love with her gym teacher, a woman named Grace. With her mother’s passing, Ellis had to rely on her father for guidance in this and all areas of life. Fortunately, his views on sexual orientation were ahead of their time as well. “She believed her father was sort of relieved that she was gay,” said a 1999 newspaper profile of Ellis. “‘He wouldn’t let me go with the boys,’ she said. ‘He would say, ‘books and boys don’t go together.’ So I think he was kind of glad I was with women because that way I wouldn’t have a baby.’”

While her father was supportive, or at least not antagonistic, it was still up to Ellis to learn about her sexuality. “I found a psychology book,” she said. “It had different things in it about different types of people. That’s how I learned. Nobody told me anything.”

Ellis met Ceciline “Babe” Franklin in the 1920s, and the two began a relationship. They moved to Detroit, where Ellis built upon some printing skills she had learned years earlier to start the Ellis and Franklin Printing Company on Oakland Avenue. She taught herself photography and ran the printing company and darkroom out of the home, creating stationery, fliers, posters, and raffle tickets for churches and small businesses in and around Detroit.

The house on Oakland also became a gathering place for LGBTQ Detroiters who had few places to socialize. “In the 1940s, ’50s, and ’60s Ruth and Babe’s home was known as the ‘Gay Spot.’ For generations of African American gays and lesbians in the Midwest, their home provided an alternative to the bar scene that discriminated against blacks. It was a haven for African Americans who came ‘out’ before the Civil Rights Movement and Stonewall,” according to promotional materials for the documentary Living With Pride: Ruth Ellis @ 100.

Ellis and Franklin were together for 30 years. In that time, hundreds of people laughed, talked, and danced at their home, where everyone was welcome.

“I’M JUST RUTH”

Ellis drew attention locally and nationally as the oldest African American lesbian in Michigan, and possibly the nation, as she approached the century mark. Newspaper profiles were written, photos were published, interviews were conducted. Ellis earned national awards. It was all strange and a bit funny to Ellis, who thought she was “just an ordinary person,” as she said to one interviewer.

Independent filmmaker Yvonne Welbon decided that Ellis was anything but ordinary. Welbon made the documentary about Ellis called Living With Pride, timed to come out in 1999, the year of Ellis’s 100th birthday. The movie highlights Ellis’s trailblazing role in creating a space where black people who were LGBTQ could fit in. It also shows her love of dancing, including a scene in which she leads the electric slide in a dance hall. She grapevines right, grapevines left, and thoroughly out-dances people half her age.

The documentary also includes an audio recording with Ellis, laughing at the idea that anyone would be interested in a film or book about her. “Who would want to read a book of my life?” she cackled. “I’m nobody. I’m just Ruth. Who would want to read it?”

Plenty of people, it turns out, wanted to learn about her. The documentary was well-received, and it led to Ellis receiving countless postcards, emails, and letters thanking her for being “just Ruth.”

“Dear Ruth: Happy 100th birthday! And thank you for being OUT and PROUD as an African American Lesbian! What a life you have had! Your love and zest for life are truly contagious,” read one email. “You reminded me of Sojourner Truth,” wrote another fan. “Ruth, you are my hero. God bless you, woman,” said another.

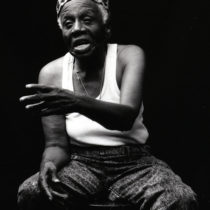

Ruth Ellis with friend Sarah Uhle in 1992.

One writer asked for advice; she knew she was a lesbian, but she loved her boyfriend, and she didn’t want to hurt him. “If it weren’t for people like you,” she wrote to Ellis, “I would feel so alone.”

Perhaps the most harrowing of the correspondences is an email from 2000, the year Ellis died, in which the writer said she was using a fake address and name. “I hope to instill in my children the ability to be true to themselves. So, I need them to see stories like yours and others who have lived their lives being true to who they are.” But she could not reveal to her husband “my attraction to this community.”

The letters highlight exactly why learning Ellis’s life story was important to so many, said Kofi Adoma, a clinical psychiatrist and activist from Detroit, in the documentary about Ellis: to help people know they are not alone, and to see how far we have come in society—as well as how far we still need to go.

“I think it’s important we know about people like Ruth Ellis because we don’t know how many are out there who are in their 80s, 90s, or even hundreds that are living an out life,” she said. “Ruth is a gift to us in that she has come out to the world. And in doing so, she has been able to share what it is like to experience triple oppression: being a woman, being black, and being a lesbian.”

THE RUTH ELLIS CENTER

In her later years, Ellis traveled with a group called the Golden Threads, an organization of elder lesbians. “I’m one of the oldest, though,” she told an interviewer in 1998. Each year on her birthday, she handed out Baby Ruth candy bars at fairs and schools.

For her 100th birthday, she planned to not only hand out candy bars but to “party all day. In fact, I think I’m going to party for two or three days—why not? I’m going to have all kinds of people at my party, gay and straight. I think sometimes now there is a bit too much separation. I love all kinds of people and I am going to dance for days.”

Today, her name, legacy, and love of life carry on at the Ruth Ellis Center in Detroit, a short- and long-term residential safe space for runaway, homeless, and at-risk LGBTQ youth, which also provides numerous support services. The young people who are helped by the center are aware of Ellis’s impact. “I think she humanized a lot of the youth here in Detroit,” says one young person in a video for the center.

Others on the video discuss their career goals, how they found a place for themselves at the center, and the importance of treating people how you would want to be treated. And they dance. They dance with smooth steps and waving arms, with abandon, with complete freedom.

Ruth Ellis surely would be proud.

Ruth Ellis’s papers at the Bentley are open to the public.

Sources:

Eichberg, Sarah. “She Helps Many Just by Being Herself.” Detroit Free Press, July 20, 1998.

Jewell, Terri. “Miss Ruth.” Does Your Mama Know?: An Anthology of Black Lesbian

Coming Out Stories. Lisa C. Moore, ed. Austin, Texas: RedBone Press, 1997. 189-196.

“Living with Pride: Ruth Ellis @ 100,” publicity notes, 1999.

Michael, Jason A. “Ruth Ellis: A century worth of history.” Between the Lines, May 2, 2003 .

“One Hundred Years of Stories,” Morning Edition, May 25, 2000.

Rogers, Lesley. “Homecoming,” The State Journal Register, May 12, 1998.

Smith, Rhonda. “100 Years Young,” Washington Blade, May 28, 1999.

“Who We Are”: Ruth Ellis Center video.

Wilkinson, Kathleen. “Portrait of a 100-Year-Old Lesbian,” Curve, November 1999.