Magazine

Love is a Battlefield

Sarah Emma Edmonds dressed as a man on the battlefield during the Civil War and risked blowing her cover when she confessed her love for a fellow soldier. This strange tale of unrequited love is documented in archived journals at the Bentley and reveals how one woman’s war-time secret finally came to light.

By Jenn McKee

As a farm girl growing up in 19th-century New Brunswick, Canada, Sarah Edmonson discovered the novel Fanny Campbell, The Female Pirate Captain: A Tale of the Revolution! and began to imagine a more unconventional, adventurous life for herself.

She didn’t have to wait long to get started.

As a teen, Edmonson’s abusive father arranged for her to be married to a significantly older man. To escape the unwanted marriage, she fled to another town, where she trained and worked in a millinery and altered her name to Edmonds.

When her father picked up her trail, Edmonds knew she needed to deepen her disguise. That’s when she donned men’s clothes and crossed the border into the United States as someone else entirely: Franklin Thompson.

As Frank Thompson, she traveled to Connecticut first, to meet with a book publisher, and sold Bibles, eventually making a home for herself in Flint, Michigan.

In 1861, at age 19, Edmonds, driven by a patriotism for her new home country, enlisted as a soldier in the Civil War. But she also soon fell in love with a fellow soldier—a strange and romantic episode that’s documented in papers at the Bentley, and that reveals the startling secret Sarah couldn’t keep.

Friendship in Exchange for Friendship

Edmonds first attempts to enlist were thwarted by her small size—the Army’s height requirement was 5’8″—but she eventually began her Army career as a nurse. She landed at a field hospital in Washington, D.C., where she met a private named Jerome Robbins, who’d come to visit a sick friend before getting a hospital position of his own.

The Bentley has nine of Robbins’ journals from this period of his life, as well as two letters Edmonds wrote to him.

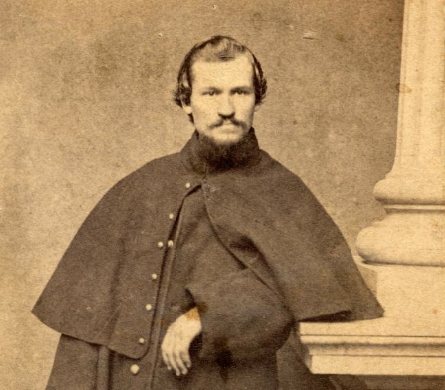

Jerome Robbins, Second Michigan Infantry, circa 1861. HS1121

The first mention of Edmonds, in the guise of Frank, is noted on October 30, 1861, when Robbins wrote, “I had a very pleasant conversation with Frank Thompson on the subject of religion.”

Indeed, both Edmonds and Robbins were guided by their faith, to such an extent that they attended prayer meetings together and often went on long walks to share their thoughts on the subject.

Robbins, though grateful for his newfound friend, began to wonder if something was amiss.

On November 11, 1861, he wrote:

“One consolation I have which I receive as a blessing: the society of a friend so pleasant as Frank I hail with joy. Though foolish though it may seem, a mystery appears to be connected with him which it is impossible for me to fathom, yet these may be false worries.”

They were not false worries, of course. As Robbins confessed his deep affections for a young woman back home in Michigan named Anna Corey, Edmonds felt compelled to reveal her true identity to Robbins.

The heading over Robbins’ journal entry for November 16, 1861 reads, “Please allow these leaves to be closed until the author’s permission is given for them opening,” underscoring the need for privacy in regard to the sensitive account.

“How sad is the reaction which often occurs when we think we have friendship in exchange for friendship and find the friend differing so widely from our own natures,” Robbins writes.

He reflects that “in friends we may be deceived,” and eventually writes plainly that although “never frankly asserted by her, it will be understood that my friend Frank is a female.”

Entrenched in Secrecy

Robbins could have been shocked enough to turn Edmonds in or tell others in the military camp. However, he keeps Edmonds’ secret, continues to call her Frank, and continues to use male pronouns.

One possible explanation for this complicity is that war had blurred gender roles and women were already on the battlefield anyway—caring for the wounded, sewing uniforms, distributing supplies, and more. According to the National Archives, an estimated 250 women fought as soldiers in the Confederate army alone.

“I am convinced that a larger number of women disguised themselves and enlisted in the service, for one cause or other, than was dreamed of,” wrote Mary Livermore in 1888. Livermore had worked for the U.S. Sanitary Commission during the Civil War, providing medical care and other services to Union soldiers. “Entrenched in secrecy, and regarded as men, they were sometimes revealed as women, by accident or casualty. Some startling histories of these military women were current in the gossip of army life.”

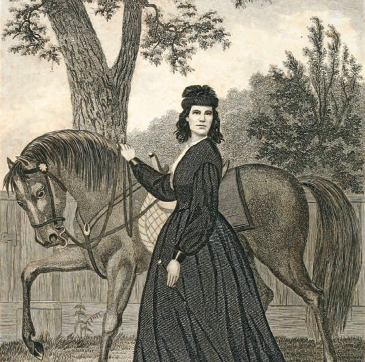

A portrait of Sarah Emma Edmonds from her book, “Nurse and Spy in the Union Army,” published in 1865.

Edmonds’ romantic feelings go unrequited at this vulnerable crossroads and, as a result, Robbins notes that her disposition turns disagreeable. He suspects her resentment is a result of his feelings toward Anna Corey back in Michigan:

“I entertain the kindest feelings [toward Edmonds], but it seems that a great change has taken place in her disposition or the real has been unmasked. . . . Perhaps a knowledge on her part that there is one Michigan home that I do regard with especial affection creates her disagreeable manner.”

Robbins comments on Edmonds appearing depressed and distant at times. She also seems to forge new relationships with others in camp. In December 1862, Robbins writes in his journal regarding Edmonds’ close friendship with a married soldier named James Reid:

“Have not had a very long chat with Frank, and I feel quite lonely without him. But I suppose he enjoys his tent mate. . . . Reid seems a fine fellow and is very fond of Frank.”

In other ways, the pair continued to cultivate the friendship as if little to nothing had changed.

For example, when Robbins was away from camp for an extended period, Edmonds left a note in his journal joking that she’d read it “for spite” and “carried away some of [his] choice magazines.”

A January 16, 1863 letter from her to Robbins, openly signed as “Emma,” finally offers some emotional candor in her own voice, reading:

“I am happy to know that you are prospering so well in matters of the heart. In spite of the ridicule which sentiment meets with everywhere, I am free to state that upon the success of our love-schemes depends very much of our happiness in this world. … Dear Jerome, I am in earnest in my congratulations and daily realize that had I met you some years ago, I might have been much happier now. … I do not love you less because you love another, but rather more, for your nobleness of character displayed in your love for her.”

From Desertion to Pension

Soon thereafter, when Edmonds suffered worsening malaria symptoms, she abandoned her post to seek out medical treatment in Ohio in April 1863. Though she’d hoped to return to the Army once she was well, posters labeling her a deserter had circulated, so that option vanished, and she began a new life as a woman again.

Robbins had initially thought some logistic mishap befell Edmonds, but after a few more days of absence, he wrote:

“I have learned another lesson in the great book of human nature. Frank has deserted, for which I do not blame him. His was a strange history. He prepared me for his departure in part. Yet I did not think it would be so premature. Yet he did not prepare me for his ingratitude and rotten disregard for the finer sensibilities of others.”

Presumably unaware of Robbins’ anger, Edmonds wrote a letter on May 10, 1863 that reads:

“I dare not write you the particulars of anything now until I hear from you and know where you are, for fear it might fall into other hands. … Oh, Jerome, I do miss you so much. There is no person living whose presence would be so agreeable to me this afternoon as yours. … Be careful when you write lest it should get mislaid. Reid seems to think that you are the only friend I have in camp. It may be so, but had hoped that I had one or two more at least.”

Robbins’ military career continued after Edmonds left camp. He mustered on January 1, 1864, at Blain’s Cross, Tennessee, and was honorably discharged on July 28, 1865.

In the end, Robbins returned to Michigan, but his romance with Anna Corey ended with her marriage to another. In 1867, Robbins graduated from the University of Michigan Medical School and later lived in Boyne Falls, Michigan.

Edmonds, meanwhile, made a splash with her memoir Nurse and Spy in the Union Army in 1865, though several critics have questioned the veracity of some stories told therein. She married a man named Linus Seelye in 1867. They had three children, but all of them died in their youth, and the couple adopted two sons.

In 1876, Edmonds attended a military reunion and was welcomed and cheered by her former colleagues. She did, in fact, have friends besides Robbins in camp, and in the end, they not only helped her get the charge of desertion removed from her record, but also signed affidavits to petition for her to receive a military pension.

It took nearly a decade and an Act of Congress, but Edmonds was eventually cleared and awarded a pension; plus, in 1897, she was admitted into the Grand Army of the Republic, a Civil War Union Army veterans’ organization.

Edmonds died at age 56 on September 5, 1898, at her home in La Porte, Texas, from lingering malaria complications. She was initially buried quietly in a local cemetery but was reburied, in 1901, with full military honors at Washington Cemetery in Houston. In 1992, she was inducted into the Michigan Women’s Hall of Fame.