Magazine

Michigan’s Failed Anarchist Utopia

Founded during the Great Depression in Michigan, the Sunrise Cooperative Farm Community was created on a dream of shared labor and equality. But as records and a newly recorded oral history at the Bentley reveal, the dream was short-lived.

By Andrew Rutledge

In the fall of 1932, Joseph Jacob Cohen embarked on a cross-country tour to document the devastating effects of the Great Depression on America’s workers. Born in Russia, Cohen had immigrated to the United States in 1903 and was soon deeply involved in America’s Jewish anarchist community. Eventually, he became the editor of the most influential Yiddish anarchist newspaper in the country, Fraye Arbeter Shtime (Free Voice of Labor). His tour, he hoped, would give him the opportunity to share his beliefs, drawing converts to anarchism and increasing subscriptions to his paper.

Instead, the destitution and despair Cohen saw on his journey reignited his long-held desire to create a self-sufficient community built around anarchistic principles of self-government. Soon, he was working with a group of like-minded Jewish anarchists to locate a suitable farm for their “colony.” One member of the group, Eli Greenblatt of Detroit, discovered what seemed like the perfect location near Michigan’s “Thumb,” nine miles southwest of the city of Saginaw.

The land was beautiful—as was Cohen’s vision for a communal utopia. But as records and a new oral history captured by the Bentley reveal, the community that would become Sunrise Cooperative Farm would be both joyous and short-lived, eventually torn apart by dissension and infighting.

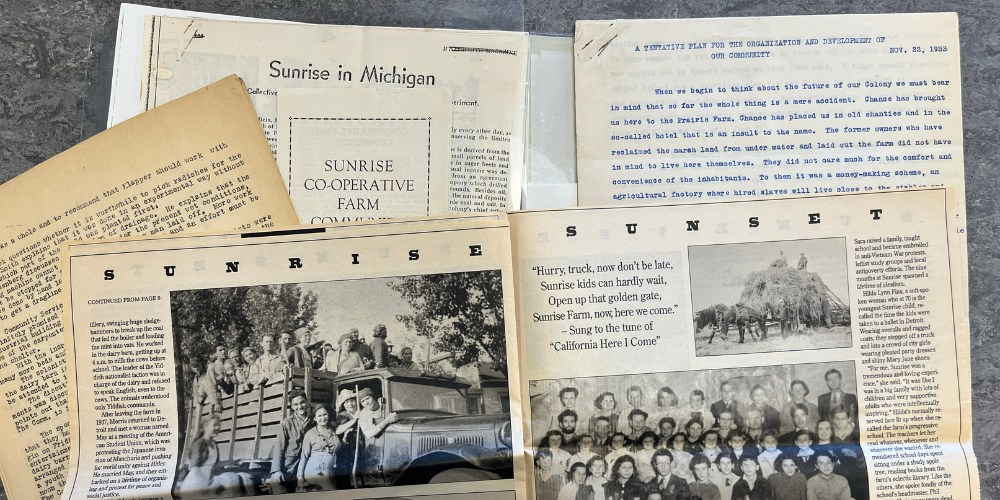

Workers in a field at the Sunrise Farm Cooperative, from the Joseph A. Labadie Collection.

Dreaming of a New World

The 10,000-acre Prairie Farm was once said to be the largest farm east of the Mississippi, producing sugar beets, peppermint, corn, and rye, as well as herds of horses and sheep. Created in the 1880s amid the prairie marshes around Saginaw, the farm’s success was due to miles of dikes and drainage ditches that spared it from the area’s frequent flooding. Nevertheless, by the 1920s it had fallen into disuse, and was eventually put up for sale.

After a wave of frantic fundraising, Cohen, Greenblatt, and several others formed a corporation to purchase Prairie Farm in March 1933. For $205,000, it became the property of the Sunrise Cooperative Farm Community—the official name for their new utopia. Contemplating its future, Cohen was exuberant, declaring that they were “building a new world, a heaven on earth, a kingdom of justice for all who would join and do their share.”

Their next task was recruiting “liberal minded people who [would] agree to live collectively and promise not to bring in fanaticism of any kind nor dogmatism.” Advertisements were published in Yiddish and English anarchist newspapers in New York, Detroit, and Chicago. To join, applicants had to be younger than 45, meet with a preliminary screening committee, pass a health examination, and pay a nonrefundable entrance fee of $500. Although theoretically anyone who met these conditions could join, most colonists were Jewish, and many had an immigrant background. There was considerable enthusiasm for the project and, by the fall of 1933, 85 families, or a total of around 250 people, had joined Sunrise.

Figuring How to Farm

The new colony envisaged by its founders would be avowedly anarchistic; they rejected any coercive structure, instead relying on members’ “natural” inclination for mutual aid as incentive for participating in communal work. On the farm, adult colonists were divided into a dozen or so teams based on their experience and interests. Each team was responsible for handling a different aspect of the farm, such as the sugar beet or dairy units. Other groups handled maintenance, cooking, and education.

Few of the colonists, however, had any real experience with farming, which led to considerable difficulties. One memorable incident involved Sunrise’s 3,400 sheep. When the hired shepherd took a vacation, the colonists were confident they could manage things. The sheep promptly wandered off and weren’t located until the shepherd’s return.

One of the few who did have experience farming was Philip Truppin. In 2023, the Bentley recorded an oral history with Truppin’s daughter, Merelyn Dolins, who spent her childhood at Sunrise and shared her memories of her father and her experiences there.

As a teenager, Truppin graduated from a “Farm School” in New York, created to prepare students for life on a kibbutz, but instead he pursued a Ph.D. at New York University. At Sunrise, his farm school experience placed him in charge of the barns and the dairy herd whose milk and butter provided one of the few consistent sources of revenue on the farm.

In addition to their lack of experience, Dolins recalled another challenge facing the new farmers: slackers. Sunrise’s founding assumption was that people, freed from capitalist society, would naturally want to work together for the benefit of all. This proved true for most, but there also emerged a small but demoralizing group who refused to work.

Some believed anarchism meant complete freedom to choose what they did. Others claimed that debates over political and social issues took precedence over everything and harangued from the back of a truck those who worked in the fields. As firm believers in free choice, there was little the other colonists could do to curtail such behavior.

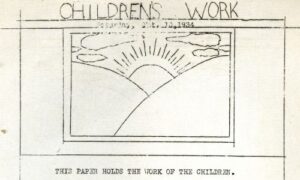

Papers relating to the Sunrise Farm Cooperative, from the Joseph A. Labadie Collection.

To Labor for Nothing

Cohen and the other founders had hoped that a spirit of cooperation would prevail, but even as the first families settled on the farm, fierce debates erupted over a host of issues. One of the loudest among the predominantly Jewish colonists was whether public meetings and the newsletter should be in Yiddish or English.

Dolins remembers “walking up and down in front of the building while they were arguing about the newsletter, and I couldn’t even figure out why they were fighting about this.” The debate lasted weeks. And while English was eventually chosen, hard feelings carried over into the much more complex discussions about creating an organizing administration for the colony—an effort that was never successful.

Factions swiftly emerged spanning a dozen political views, including anarchists, socialists, Marxist Communists, Trotskyite Communists, Yiddishists, and some not “politically minded” at all. All, however, shared the belief that anyone from a different faction than their own was plotting a “dictatorship” and mismanaging the colony’s funds. Cohen and Greenblatt were soon deeply at odds with colony members, and the latter abandoned the farm in disgust after only a few months.

Greenblatt was the first of a steady exodus of disgruntled members. Some even published articles condemning Sunrise in various anarchist papers, with one decrying that “Sunrise does not want to be built upon one’s own labor, but upon exploitation in all its forms . . . [luring] Comrades to labor for nothing.”

A Pretty Nice Place

Despite the factionalism, there was a great love for Sunrise shared by most colonists, according to Cohen’s memoirs, spurred by the sense of contributing to something greater than oneself. Dolins agrees, remembering how life at Sunrise was full of joy—particularly for the children.

Sunrise’s “Children’s Work” newsletter.

Education was an emphasis, and some of the first buildings erected were a primary school and a high school, also overseen by Truppin, who had been high school principal in North Dakota. Older children lived in a communal “children’s home,” and joined in the farm work between classes.

Educational opportunities also abounded for adults, with evening classes on everything from history to economics to animal husbandry. Playwrights, educators, activists, and social scientists from outside the farm frequently visited. There were weekly concerts, plays, and talent shows organized by the colonists. There was “singing all the time. There was constant singing,” Dolins recalls. And she particularly remembers the grand celebrations held every June to celebrate the anniversary of the farm’s purchase.

Eleven-year-old Melvin Weinstock captured colonists’ affection for the farm in his 1936 poem “Sunrise,” published in the school newsletter:

Sunrise is a pretty nice place,

Of bosses there is not a trace,

We all like it a lot, I think…

I like to stay, I like to stay,

I wonder how I can go away.

That would be a dreadful thing.

Not to hear the birdies sing

I surely would hate to leave Sunrise,

Even though there are mosquitoes and flies.

Endings and Legacies

Yet by the time Weinstock penned his poem, Sunrise Farm was on the brink of disintegration. Financial difficulties were made worse by dwindling numbers of colonists who left out of frustration or to seek work in the cities slowly recovering from the Depression. A lawsuit filed by a former member in May 1936 accusing the colony’s leadership of fraud was eventually dismissed, but demanded precious time and funds to fight. An effort to sell the farm to the Department of Agriculture in return for support to maintain the colony as a “cooperative community” fell through—but the sale did not. On December 7, 1936, Sunrise Farm was sold to the federal government.

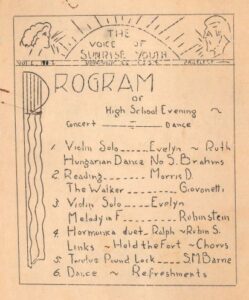

The Voice of Sunrise Youth publication.

Cohen, Truppin, and a dozen other families tried to continue their dream by moving to another farm in Virginia in early 1937. But the same problems from Sunrise appeared again and the breakdown of the friendship between Cohen and Truppin was the final straw. The last family left the new farm in 1940.

“There were a lot of negative things that happened…all the arguments and the difficulties it went through…But I think it also had a lot of idealism,” Dolins recalls. Despite its brief existence, Sunrise left a deep impression on nearly all its residents. This was particularly true for the children, according to Dolins, many of whom went on to become educators and advocates for social justice, keeping Cohen’s dream of building “a kingdom of justice for all” alive.

Merelyn Dolins’s oral history and the Sunrise Cooperative Farm Community records are open to the public.