Magazine

No Resignation

Renowned neuroanatomist Elizabeth Crosby was a brilliant researcher and a dedicated teacher whose students adored her. She spoke of her many years at U-M with fondness. So what happened to make her attempt to resign numerous times over the course of her career? Letters in her collection may provide answers.

by Lara Zielin

On October 15, 1937, the chair of U-M’s Department of Anatomy, Bradly Patten, received a letter of resignation that spurred him into action.

It was from professor Elizabeth Crosby, a star in the field of neuroanatomy, and she was leaving U-M.

Patten immediately wrote to the dean of the Medical School, Albert Carl Furstenberg.

“I do not know what is behind Doctor Crosby’s letter of resignation. Whatever it is, I hope you will join me in trying to persuade her to change her mind. We don’t want to lose her.”

Furstenberg quickly wrote to Crosby, reminding her that she had the “profound admiration and respect of the President of the university, myself, the Director of your Department, and every member of the Medical Faculty, as well as the student body.” He offered his most “sympathetic help” to understand her problem, and asked if she might pay him a visit “at her earliest convenience.”

There’s no record of Crosby writing back, or visiting him, but whatever Furstenberg said to her in subsequent meetings must have worked. The storm passed, and Crosby stayed.

For the time being.

This wasn’t Crosby’s first time resigning—and it wouldn’t be her last. All told, over the course of her brilliant career at U-M, she would attempt to resign at least four times. And each time, her department chair and the dean of the Medical School would try to change her mind.

It’s an odd pattern for a researcher and professor who was so highly regarded, and who said of U-M, “I only feel gratitude for my time at U-M. I tried hard and I never asked for a raise or promotion but I always got one. I just had a good time.”

What could have caused so many rifts? Letters and records at the Bentley reveal clues about what could have been going on behind the scenes, and how Crosby may have been struggling as a woman in a male-dominated field.

A Beautiful Mind

Elizabeth Crosby was born in 1888 in Petersburg, a small farming community in southeastern Michigan. She was so frail at birth that she almost died, and so sickly that her parents would sometimes “put her in the oven for short spells to bring the color back into her cheeks.”

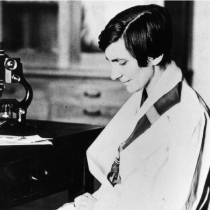

Elizabeth Crosby lecturing in this undated photo. In the course of her career, Crosby had taught more than 8,000 students.

Crosby’s mind, however, flourished. After graduating from Adrian College in 1910, Crosby attended the University of Chicago, where she was determined to take classes from C. Judson Herrick, a respected neuroanatomist. This, in spite of the fact that she’d only ever taken basic biology and elementary zoology.

Herrick was reluctant to let her in, but after she insisted, he finally acquiesced. Within a few weeks, Herrick wrote, “she was doing as well as the medical students.”

Through Herrick, she was introduced to neuroanatomy, the subject that would become her lifelong passion.

Crosby earned her Ph.D. in neuroanatomy in 1915, producing a groundbreaking thesis titled “The Forebrain of Alligator mississippiensis,” in which she meticulously dissected the brain of an alligator and drew what she saw. The work remains important today.

After graduation, Crosby returned to Michigan to care for her aging parents. After her mother died in 1918, she and her father moved to Ann Arbor, where Crosby became a junior instructor at the University of Michigan under Carl Huber, a professor of anatomy.

Huber and Crosby became close and effective collaborators. “Their minds and hands almost automatically worked to the same ends,” wrote Russell T. Woodburne, a U-M professor of anatomy, in a short biographical sketch of Crosby. “She has stated that most of her research was inspired by Doctor Huber and that he was the source of much valuable training. He, in turn, regarded her as one of the outstanding research investigators in comparative neurology as well as a superb teacher.”

Together, Crosby and Huber produced the 1,800- page work The Comparative Anatomy of the Nervous System of Vertebrates, Including Man. It was comprehensive, accurate, and so detailed that its authority was accepted almost immediately.

Tragically, before it could be published, Huber died in the fall of 1934. “No one will ever be able to assess the shock and sense of loss which this event caused Doctor Crosby,” wrote Woodburne.

It also left Crosby’s role in the department in limbo. By the spring of 1935, her resignation letters had begun.

“A Source of Embarrassment”

Crosby wrote her first resignation letter to Dean Furstenberg on February 21, 1935. She began by citing her gratitude for her promotions from junior instructor to associate professor, and said that she “always had adequate compensation and have been given every opportunity to do the work that I wished to do.”

The problem, however, was with her gender.

“It would seem that a woman in my position, as second ranking member in the Anatomy Department, might, under all the circumstances, prove a source of embarrassment to you as Dean and to the Executive Faculty of the Medical School. This has been apparent to me since Dr. Huber’s death . . . .”

Until then, Crosby’s role as a brilliant researcher and teacher was both protected and validated by her close collaboration with Huber, who was the head of the Anatomy Department and dean of the Graduate School. The pair had a great vision for brain research at Michigan, but with Huber gone, she perceived her position as precarious.

“It is quite probable that the University may feel that they should bring in someone from outside to carry out this program,” Crosby wrote to Furstenberg. “In that event, it does not seem to me that there is any place left for me.”

She proposed to Furstenberg that she be demoted and returned to a quizmaster and laboratory assistant until she could find a different position at another university—unless Furstenberg could find any “middle course” in the situation.

As Furstenberg considered the circumstances— and presumably worked to find Huber’s replacement— friends counseled Crosby to stay put and not do anything rash.

“It would be a great loss to neurology in America if you were to give up your place at Michigan,” wrote Stephen Walter Ranson, a colleague working at Northwestern Medical School, on March 19, 1935. “You will make no mistake in staying at Michigan for a year or two more until you know just how things are working out there.”

Cooler heads prevailed, and Crosby stayed put. A year later, her fortunes would change again, at least on paper.

Patten’s Folly

In early 1936, Bradley Patten became the new chair of the Department of Anatomy, replacing Huber. He had degrees from Harvard and Dartmouth, and would serve at Michigan until his retirement on September 1, 1959.

Patten’s action on Crosby was swift. By April 1936, he’d written to Furstenberg recommending Crosby for the position of full professor in the Medical School.

“Dr. Crosby is one of those unassuming persons whose brilliant work has been done so quietly that one finds her almost better known abroad than within her own University. I feel strongly that…the stimulus and confidence given to her by such recognition at this time will make for a stronger and better-rounded development of the work of the Department in the coming years.”

Crosby accepted, becoming the first woman to hold a full professorship in the Medical School.

But her October 1937 resignation letter (cited at the start of this story) wasn’t far off.

Crosby’s would-be biographer, Richard Schneider, may have uncovered clues that her working conditions at the time were far from ideal.

Schneider was an internationally respected neurosurgeon who practiced and taught at U-M beginning in 1950. He collaborated with Crosby in his work, and was also close with her personally. When she died in 1983, he was designated as the representative of her estate.

Bradley Patten (far left), Robert D. Lockhart (middle), and Elizabeth Crosby investigate an unidentified scientific sample circa 1950. HS11594

Soon after Crosby died, he began a biography of her, reaching out to colleagues and friends who knew her best in order to shed light not just on her scientific contributions, but her personal life and the “tremendous odds that she had to overcome in order to continue to do her work.”

In the course of his research, Schneider received a letter from Dr. John Bean, a Medical School graduate who had joined the faculty in 1944, eventually becoming chair of the Department of Physiology.

He told Schneider that Crosby and Patten’s relationship was strained. “I gather that Patten was a bit envious of Crosby’s reputation and tried to introduce features into Crosby’s courses which were not to her liking.”

Such as the time when Patten forced Crosby to build and use an enormous life-size model of the entire human nervous system for her classes, with wires for nerves. The Anatomy Department called it “Patten’s folly.”

Patten also dismantled a special research library Crosby had developed with Huber, according to Bean. Patten even insisted Crosby retire before him so that “any honors which might be due [Patten] would not be dismantled by her greater reputation.”

Crosby herself confirms that Patten had set a retirement date that she was certain wasn’t right. “I was quite sure . . . that the time set was not correct, but I thought that Dr. Patten wished me to retire a year before he did,” she wrote in a 1956 letter.

Ultimately, Crosby’s retirement date was corrected by faculty in the department. She and Patten both retired in 1959.

“Despite her statements . . . that she never was discriminated against, it seems to me that this was [a] real cover up, for she had a major degree of discrimination in actuality,” wrote Schneider.

Others concur. When The Comparative Anatomy of the Nervous System of Vertebrates, Including Man was published, Crosby insisted on her name being third in the list of contributors, even though she wrote most of the book.

“Crosby’s willingness to share the public limelight with her colleagues may have been an unwitting discovery of a survival technique for a woman in science,” writes Leslie Lin a 1983 article in the University of Michigan Research News, produced in conjunction with six Medical School faculty. “Her apparent disinterest in recognition undoubtedly helped her excel while minimizing antagonism or defensive reactions from male peers.”

U-M Professor Muriel Ross, a student of Crosby, recalls hearing Crosby say that Huber approved of Crosby’s name on co-authored papers, but didn’t think it “quite proper” for her to speak publicly.

Persevering

Crosby acknowledged that women in her field had experienced discrimination, but never counted herself among them. “I’ve had as much opportunity as a man,” she insisted.

Crosby’s attitude, writes Lin in the Research News, “seems typical of her generation’s female scientists. They asked for so little that any recognition they did achieve was regarded as a ‘bonus’ rather than their due.”

Still, after her 1937 resignation attempt, Crosby would almost leave twice more—considering offers from the University of Aberdeen in Scotland and Marquette University in Wisconsin.

U-M won out in the end, and Crosby worked for the University for decades, even after her retirement in 1959.

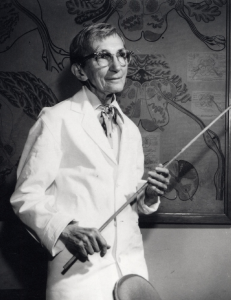

Elizabeth Crosby receives the National Medal of Science from President Jimmy Carter in 1980.

Ten women wrote their doctoral dissertations under Crosby. She taught more than 8,500 students, and she persevered in spite of osteoporosis, partial deafness, and other physical limitations.

Before her death, she was honored by every major professional organization in her field. In 1980, she received the National Medal of Science from President Jimmy Carter.

Crosby died in 1983 and is buried in her hometown of Petersburg, Michigan.

Sources for this story include:

The Elizabeth Crosby Papers. Lin, Leslie: The Research News, University of Michigan, August-September 1933. Whitehouse, Bradley: “The Quiet Genius,” Adrian College Contact, Winter 2005.