Magazine

On the (Treasure) Hunt

by Lara Zielin and Deb Thompson

Ross J. Wilhelm was an esteemed professor of business economics at the University of Michigan, well known for his prediction of the 1970s energy crisis, as well as his voice on the popular radio show Business Review, broadcast on more than 100 stations throughout the United States.

So why, then, does his collection at the Bentley Historical Library contain folders full of strange symbols and ciphers, complex drawings and codes, and references to an obscure 16th century text?

The answer begins with Wilhelm’s experience in World War II, and ends with a small island off the coast of Nova Scotia. Wilhelm left Ohio State University in 1942 to serve in the Army in World War II, and was put to work in counterintelligence at Camp Hulen, Texas, under General H.C. Allen. As part of his training, he studied De Furtivis Literarum Notis, a book on cryptography by Giovanni Battista Porta, published in 1563.

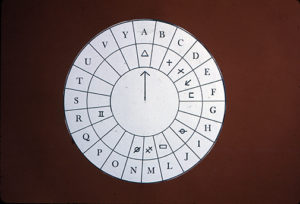

A recreation of the cipher disk that helped Ross Wilhelm crack the code on the fabled Oak Island tablet.

The book would play a role again in Wilhelm’s life, but not for many years—after the war ended and he was awarded an Army Commendation Ribbon for his service; after he received his bachelor’s degree and a master’s in business from Case Western Reserve University and his Ph.D. from U-M (in 1947, 1948, and 1962, respectively); after he became an associate professor of business economics at the University of Michigan; and after he read a story about a fabled treasure buried on Oak Island off the coast of Nova Scotia.

The Oak Island treasure lore began in 1795, when three young men found a depression on the island and started to dig. Around 70 feet down, they reportedly discovered a flat stone on which several symbols were carved. They kept digging, but were halted by seawater seeping into the dig site—the same problem that has plagued the island’s treasure hunters in the centuries since.

Though the stone itself has been lost to time, recreations of the symbols remain. Those symbols were included in a three-part Detroit News story on Oak Island in 1970, which Wilhelm read, and which brought Giovanni Battista Porta’s book back into his mind: The symbols were the same as those he’d studied during WWII. Using the cipher disks in Porta’s book, Wilhelm set to work on breaking the code, which he believed was the key to unlocking the treasure vault without letting seawater in.

Trying different language combinations, Wilhelm eventually landed on a message in Spanish that translates to:

“At eighty guide, maize or millet estuary or firth drain F”

According to a 1971 article in the U-M Business School’s Dividend magazine tucked away in Wilhelm’s collection, the code explains that adding maize to the drains would soak up the water and prevent flooding, thereby granting access to the treasure. The F, he believed, is a kind of pun, intended to be F II or a reference to King Philip II of Spain.

Even though he believed he’d cracked the code, Wilhelm was doubtful that it would lead to any treasure. Philip II and the Spanish crown were in bankruptcy numerous times, and the Dividend article hypothesizes that Philip would have cleared out any gold on the island. Today, a History Channel show, the Curse of Oak Island, follows a brand new crew digging for treasure, though to date they haven’t found much of value.

Wilhelm died unexpectedly in 1983 at age 63. His collection contains detailed notes about the Oak Island cipher and is open to the public—treasure hunters included.