Magazine

Playing Favorites

With more than 75,000 feet of archived materials, 80,000 printed volumes, 136 terabytes of digital material—and much more—it’s challenging to pick a favorite object from the collections. Still, some special holdings have made an indelible mark on the hearts and minds of staff, who were happy to share their top picks.

Enjoy these staff favorites from the archives:

Cropsey’s Creation

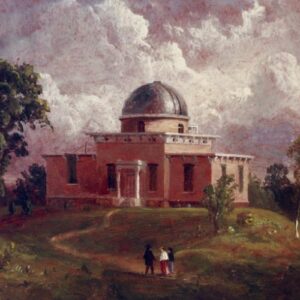

The University of Michigan proclaimed its intention to be a research institution with the construction of an observatory in 1854.

Jasper Cropsey painting of the Detroit Observatory in Ann Arbor.

A year later, artist Jasper Cropsey captured the building in vivid oils, making it the first known image of a facility known today as the Judy and Stanley Frankel Detroit Observatory. The building became part of the Bentley Historical Library in 2005.

Cropsey was friends with U-M President Henry P. Tappan, who brought the 32-year-old painter to Ann Arbor in 1855 to depict the young campus on canvas. Cropsey created two paintings—one of the handful of buildings and open field that we know today as the Diag, and another of the new Detroit Observatory to the northeast of campus.

The painting is a favorite of Austin Edmister, the Observatory’s assistant director for astronomy.

“By itself, it’s a beautiful painting by a renowned landscape artist,” he says. “It’s also really unique in that it documents a structure that is a combination of 19th century astronomical observatories and 19th century Ann Arbor architectural trends.”

Cropsey had studied both art and architecture and had an excellent reputation as an artist. “Although predominantly a painter of nature, Cropsey was also interested in man-made structures and considered them worthy subjects for his paintings,” wrote Anthony M. Speiser, director of the Newington-Cropsey Foundation. “Perhaps because of his architectural background, he often depicted buildings and other structures, elements that were usually incorporated into his landscape compositions in a manner that blended them into the natural setting.”

The Cropsey painting is on loan from the Bentley Library and can be seen at the U-M Museum of Art.

A Dear Diary

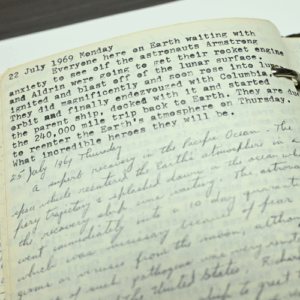

Historical diary photo from July 1969 about the first moon landing. Photo by Lon Horwedel.

Professor David M. Gates was a prolific diarist. A U-M graduate and botanist who led the U-M Biological Station in northern Michigan from 1971–1991, his papers at the Bentley include journals and notebooks filled to the edges with tight handwriting about events monumental (“I broke down and cried bitterly” after the assassination of President John F. Kennedy) and trivial (“meetings all day today”).

Gates began keeping a journal in 1935. Along with recording his thoughts, he tucked clippings, photos, identification cards, postage stamps, and ticket stubs between journal pages.

Archivist Steven Gentry is a fan of the Gates papers because it was one of the first collections he processed after joining the Bentley in 2019. He also appreciates the poignancy of Gates’ thoughts through the decades until he died in 2016.

“The most powerful entry of all was that he continued journaling even as he lay dying, with the final entry in the last journal being penned by one of his children noting his passing,” he says.

Music Notes

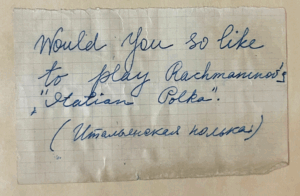

In 1961, the Kennedy administration sent the U-M Symphony Band to the Soviet Union in the hopes of thawing relations between the two countries through music. The musicians’ warm reception is evidenced in notes that are a favorite for Olga Virakhovskaya, assistant director for collections management.

A note asking for the U-M band to play an “Italian Polka” by Rachmaninov.

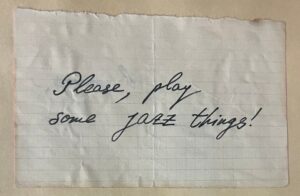

A note asking the band to “play some jazz things,” Symphony Band 1961 Tour Collection.

The small scraps of paper, tightly folded, “were often passed through the crowd to the performers to indicate their wish for unity or to say thanks,” says Virakhovskaya.

There were also requests. “Please play some jazz things!” reads one note. Another asks for Rachmaninov’s Italian Polka.

“This group visited during the Cold War, and here is an example of people opening up to each other even though they’re supposed to be enemies,” says Virakhovskaya, who is Russian. “It touches my soul.”

Listening to Students

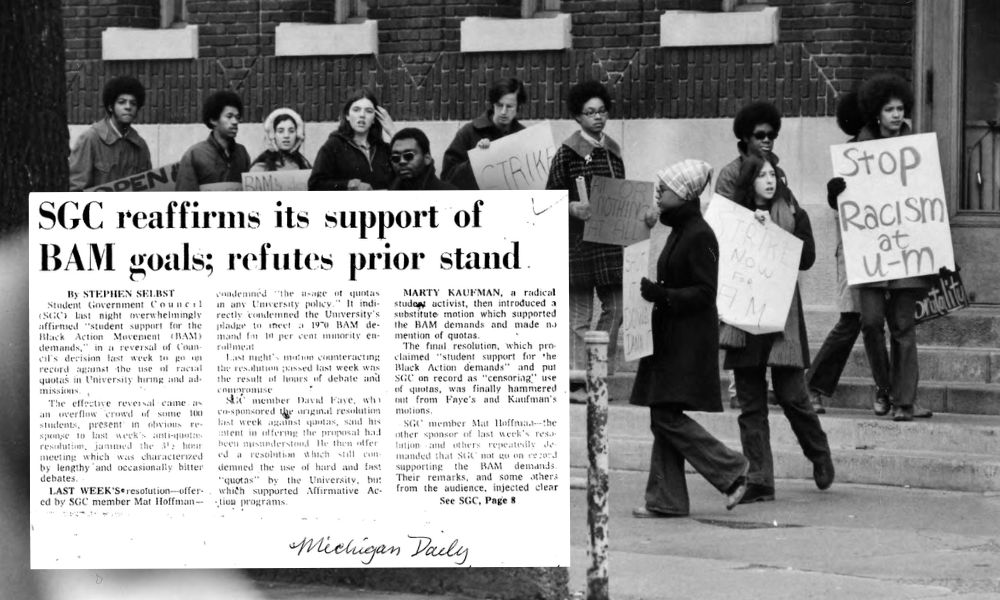

Racist graffiti on the dorm-room doors of two Black U-M students. Slurs spray painted on the iconic U-M rock. A decline in Black enrollment. This was the climate in 2014 when hate-filled flyers started appearing on campus, many of them more than just paper: white supremacists had been rigging them with harmful objects such as razor blades.

“Be careful . . . have some gloves on hand,” advised Austin McCoy, then a Ph.D. student and postdoctoral fellow at U-M, and one of the leaders of the Being Black at the University of Michigan (#BBUM) campaign.

#BBUM ignited protests and walk-outs on campus and ultimately brought a set of demands to U-M leadership, one of which was the “increased exposure of all documents within the Bentley Library. There should be transparency about the University and its past dealings with race relations.”

Part of the material relevant to the demand was housed in the archived papers of the Department of Afroamerican and African Studies (DAAS). But accessing those materials meant making an appointment and coming to the Bentley in person.

A historical article about the Black Action Movement (BAM) protests at U-M from the Michigan Daily in the DAAS records, and a photo of BAM protesters.

“We realize that archives can be confusing to use and, in this case, there was understandable concern that we were hiding the university’s history,” says Bentley Associate Director of Curation Max Eckard.

In light of this, the Bentley digitized more than 65,000 documents and 1,116 audiovisual materials for a total of 1.9 terabytes in content. All of it was made available online.

These digital materials are now a favorite for Eckard. “This collection is a good example of being responsive to the community. We wanted the students to know we were listening.”

Mining for History

Victor Lemmer was a businessman and historian from the city of Ironwood in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. His papers, including letters, research notes, and photographs, are favorites of Bentley Assistant Director for Reference Services Diana Bachman.

“In reference, we’re usually looking up material about others’ interests,” Bachman says. “As a ‘Yooper’ [someone born in the Upper Peninsula], the Lemmer papers was the first collection I investigated on my own to start looking at the Bentley’s Upper Peninsula holdings.”

Lemmer’s photographs show miners wearing candles strapped to their helmets, a stark contrast to modern electric lamps. The Upper Peninsula’s copper and iron deposits made mining a crucial part of its industry, and miners like these shaped Michigan, both through trade and through strikes for rights, pay, and safety.

Miners in the Quincy Mine, located in the Upper Peninsula, from the Victor Lemmer papers.

By collecting these photos, as well as World War II correspondence with soldiers from Gogebic County, details about local buildings, logging, mining, and more, Lemmer preserved local history that might not otherwise have been saved.

An Abolitionist Poet

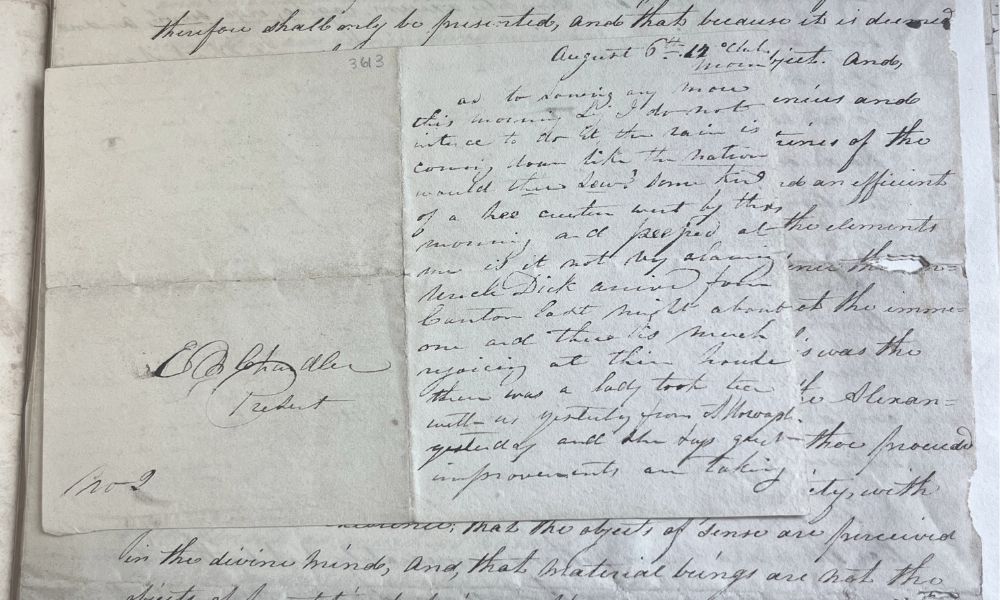

The rare and engaging Elizabeth Margaret Chandler papers are a source of inspiration for Alexis Antracoli, director of the Bentley Historical Library.

A writer and opponent of slavery, Chandler rose to fame when her 1825 poem, “The Slave-Ship,” appeared in a Philadelphia magazine.

The papers remind Antracoli of her love of early American history, the city of Philadelphia, and the writings of young women of the early 19th century.

Letters from the Elizabeth Chandler collection. Photo by Lon Horwedel.

“While Chandler stood out from the crowd in many ways, she was well-educated, came from a family of some means, and was a successful published author and well-known abolitionist. I’m always drawn to materials that give us insight into the inner lives of young women from earlier periods of time.”

Recycling History

A still image from a recycling video, from the Ann Arbor records.

“The road starts right here, with our decisions about recycling,” says the driver of a recycling truck in a video from the City of Ann Arbor. The truck is a cartoon, drawn around an actor who is speaking lines and turning a fake steering wheel.

It’s exactly the kind of public service announcement that Archivist for Digital Curation Elena Colón-Marrero enjoys.

“I like watching PSA videos from local government agencies,” Colón-Marrero says. “They are usually earnest, cheesy, and incredibly creative in a way that really captures the spirit of local government.”

Colón-Marrero says she appreciates “the effort to educate the public about recycling,” and has even used some of the tips, but that she refers to the City of Ann Arbor’s website for the most up-to-date information.

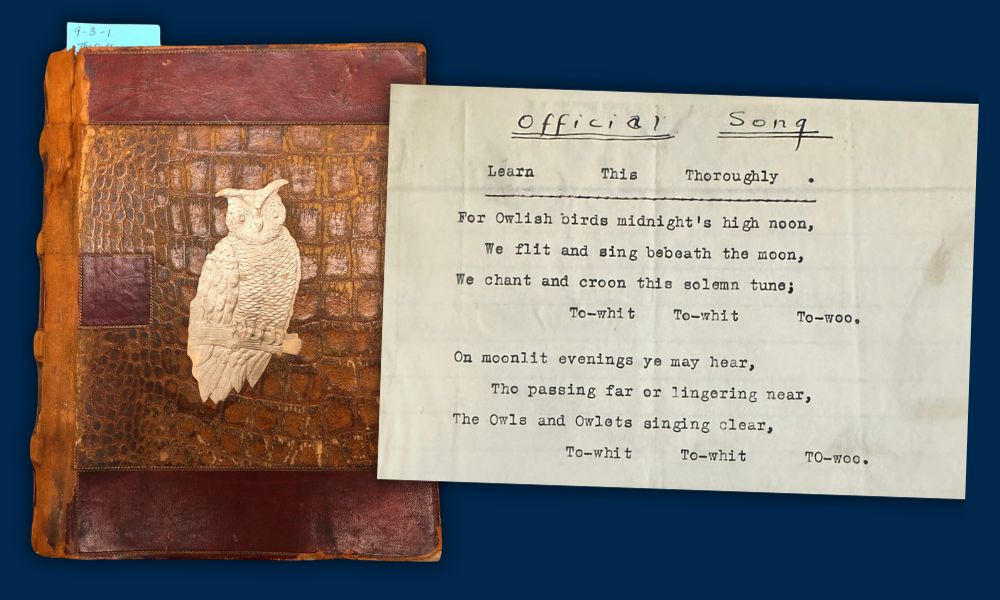

Student Owls

An owl-themed record book is a whimsical piece of student history, and a favorite of Communications Specialist Madeleine Bradford. It was created by the “Owls,” a U-M social fraternity also known as Gamma Delta Nu, which existed from 1899–1910.

According to the record book, initiates were called “fledglings,” and their password was an owl call: “to-whit, to-whit, to-woo.”

The record book and official song of the “Owls.” Photos by Lon Horwedel.

They weren’t the first with this mascot: an earlier secret society called “The Owls” fostered friendships between U-M fraternities from 1860–1870. Gamma Delta Nu claimed (without evidence, Bradford notes) to be a secret continuation of those earlier “Owls.”

“I love that there were historical secret societies themed after owls,” Bradford says. “Digging into these joyful, unexpected details, that’s part of the fun of research.”

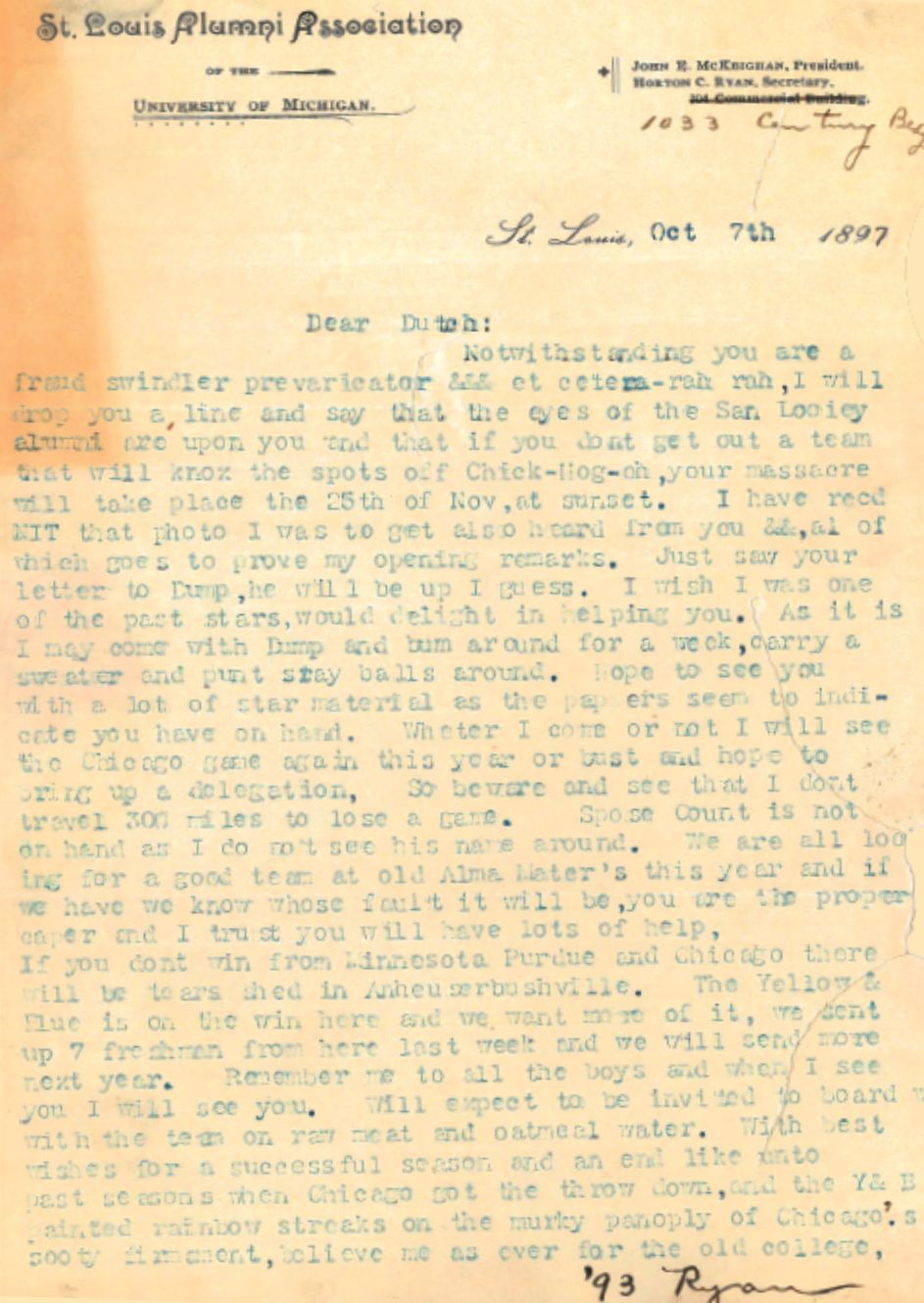

Dear Dutch

Letter to “Dutch” about football, dated October 7, 1897, Board in Control of Intercollegiate Athletics records.

On November 25, 1897, the U-M football team was slated to play the University of Chicago in the last game of the season.

Before the showdown, U-M Coach Gustave “Dutch” Ferbert received a letter from Horton Ryan, secretary of the U-M Alumni Association group in St. Louis.

Filled with deliberate misspellings and a joking tone, Ryan calls Ferbert a “fraud swindler prevaricator [sic]” and says “the eyes of the San Looiey [St. Louis] alumni are upon you.” Ryan demands U-M must “knox [sic] the spots off Chick-liog-oh [Chicago].”

The letter is a favorite of Athletics Archivist jay winkler, who says it is a humanizing moment among “mostly serious correspondence about the business of operating the football team.”

Surrounded by contracts and plans to schedule football games, winkler marvels at this ribbing among friends.

“It helps speak to Dutch Ferbert, the actual person who had a personality that apparently enjoyed over-the-top teasing.”

Both Typical and Unusual

When Josephine Gomon died in 1975, after decades of service to the less fortunate of Detroit, the Detroit Free Press hailed her as “the city’s conscience.”

Gomon was among the most influential women in the Motor City for half a century. And for just as long, she recorded her thoughts in diaries now held by the Bentley Historical Library, providing an insider’s view of the people and politics of Michigan’s largest city.

Josephine Gomon, from the Josephine Fellows Gomon papers.

Gomon worked with attorney Clarence Darrow, Mayor Frank Murphy, and industrialist Henry Ford. She fought for housing and food for low-income Detroiters, promoted birth control, and helped establish the ACLU in Michigan.

The diaries resonate with Michelle McClellan, Johanna Meijer Magoon Principal Archivist. “She started writing more than 100 years ago, and yet it sounds so relatable, especially as a wife and mother juggling a busy life. She was both typical and unusual, her voice and sense of self.”

Beauty in the Everyday

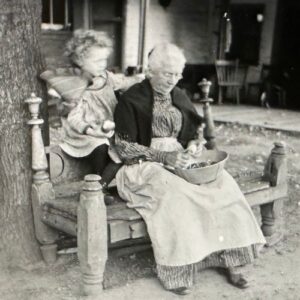

More than 100 years ago, Ypsilanti farmer Ella Fuller snapped photographs of her everyday life, including her family, farmyard animals, horse-drawn buggies, and more. Ella’s photos and glass negatives live on in the archives, and they are favorites of Reference Assistant Karen Wight.

“This collection is fascinating,” Wight says, “especially for those of us with farmers in our ancestry.”

Taken between the 1890s and the 1910s, these photos provide a unique glimpse into Ypsilanti’s past, showcasing posed family portraits, alongside more relaxed, unvarnished images of farmyard life. In Ella’s photos, women laugh, and energetic children blur with movement.

“I have a real interest in genealogy,” Wight says. “I love photos like these because I know my own family lived this way.”

A grandmother with a child peeling apples.

A woman standing with a calf on a farm.

A family flower-picking photo.

Horse and buggy in front of a farmhouse.