Magazine

Please Forgive Me. – Jerry

Provocative, offensive, and often hilarious, the Detroit-based magazines Orbit, Fun, and White Noise recently found a home at the Bentley. Their creator never intended for the publications to be taken seriously. But as it turns out, there’s a lot more going on in those pages than raunchy jokes.

by Dan Shine

Among the 70,000 linear feet of letters, photos, and books at the Bentley are copies of police reports from the unsolved murder of State Senator Warren Hooper in 1945, the signature of serial killer H.H. Holmes, and photos from an uncanny, long-haired religious baseball team. So the papers of Jerry Peterson, better known in Detroit art and music circles by his nom de punk Jerry Vile, should feel right at home. After all, this is a man who said he likes upsetting people because, “I believe that’s my art.”

He published two, often antisocial, culture and humor magazines that once ran articles on how to be a better stalker and a guide to suicide, featured an advice column written by the office cat (sample question: I’m dating a Siamese twin. How do I get her alone?), included a Detroit board game (Forgot to Hide Money in Sock, Go Back ), was full of risqué lingerie ads, and featured a Peanuts cartoon spoof that prompted a “cease and desist” letter from Charles Schulz.

It’s all now stored in eight boxes, sharing climate-controlled quarters with the papers of former Michigan governors and politicians, letters from past University of Michigan presidents and scholars, and some of the edgier pieces in the Bentley collection.

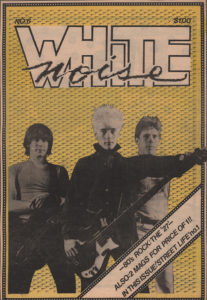

White Noise cover from the Vile collection, issue no. 6.

“Sound of hand smacking forehead,” Vile says about having his work archived at the Bentley. “If I had known things I was going to do in my life would end up [there], I would’ve done a better job.”

In fairness, two of Vile’s magazines, Fun and Orbit, covered Detroit’s underground cultural scene far better than the mainstream press and lampooned life in the city with such intelligent (and at times, juvenile) humor that they attracted a cult following. Vile’s publications were the first to write about music up-and-comers such as The White Stripes, Kid Rock, and Derrick May and the burgeoning techno music scene in Detroit. Hollywood director Quentin Tarantino was such a fan of Orbit that he wore the magazine’s T-shirt in a scene from his film Pulp Fiction.Vile said he was influenced by National Lampoon, MAD magazine, and underground comics. He was inspired by Punk magazine, which showed you could self-publish. Magazines such as Search & Destroy and Slash demonstrated that production could be cheap.

Bored, Bored, Bored

Vile’s first foray into magazine publishing was White Noise, which covered Detroit’s punk rock music scene from 1978 to 1980. Vile was the lead singer of a punk band called The Boners around the same time. In 1986, he came back with Fun: The Magazine for Swinging Intelectuals (yes, “intellectuals” is misspelled on purpose). An editor’s note in the first issue answered why: “The only reason Fun was started because we were bored, bored, bored!!! We are sick to death of living in a city that celebrates mediocrity. The uninitiated stay afraid, and the underground complains. Unlike the established papers, we are aware of what’s going on. Unlike the ‘alternative’ papers, we will write about what’s going on. …All we ask is that you don’t take us seriously. We promise never to take you seriously.” It ended with a plea for readers to ask store owners to advertise in Fun. “If they tell you no, steal something.”

Jerry Vile at the Dirty Show, the annual erotic art exhibit he created in Detroit. Photo by Nick Hagen.

Although Vile’s magazines were sometimes accused of picking on Detroit, other communities were often caught in its crosshairs. One Fun magazine feature was a mock catalog for fictitious Melvindale Community College. Under “College of Engineering” was the course Applied Petroleum Sciences 101. “You will learn the skills needed to supply internal combustion engines with hi-octane petroleum and lubricants,” the course description read. For the Business School, there was Dress for Success 220: “Clothes are an essential part of an executive wardrobe. Materials fee $2.00 for hair-net.”

Orbit’s final issue was in fall 1999. Vile signed off with one last message to a special reader: “I’m sorry God. I don’t know why I said those horrible things. I guess I was just showing off, for the readers. I don’t want to be a wretch. And I don’t wanna go to hell. Please forgive me. Jerry.”

A Digital Memory Hole

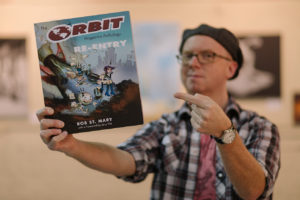

Vile’s work might have ended up in attics, basements, or recycling bins—certainly not at the Bentley — if it weren’t for Rob St. Mary, a fan of Orbit who wrote The Orbit Magazine Anthology: Re-Entry, about all three of Vile’s magazines. Vile says St. Mary did a “bang-up job” on the book, which was published in 2015.

“It is a ton of work to put something like that together,” he says. “He knows more about the magazines than I do.”

When he was done with the project, St. Mary tried to return the old issues and research materials back to Vile, who is now an artist best known for organizing the Dirty Show, an annual erotic art exhibition. Vile told St. Mary to keep it, but the author didn’t want 170-plus issues of Fun and Orbit sitting on the floor of his closet. He remembered a conversation with an Oak Park, Michigan, bookstore owner who said the Bentley had a great collection of media from the state, including the Detroit dailies, defunct newspapers, and the underground press of the 1960s. St. Mary contacted the Bentley and was told the Library would love to have the Vile materials.

Researching and preserving history comes naturally to St. Mary. Growing up, his father was interested in genealogy so the young boy would tag along to libraries in Michigan and Canada to go through microfilm and microfiche looking for wedding announcements and death notices. They also would go to graveyards and do headstone rubbings. Additionally, St. Mary, who works for the civic crowdfunding agency Patronicity, spent a portion of his career as a journalist, including 15 years as a commercial and public radio reporter, and an arts and culture podcaster for the Detroit Free Press.

“Working in radio, one of the things that I realized is that a lot of our stuff wasn’t saved,” he says. St. Mary worries that important things will be lost down a “digital memory hole.”

“Hard copies of things have always been important,” he says. “We need a place where that stuff can be saved and it can be lovingly cared for.”

The Absurdity of Things

For St. Mary, the book represented a lifelong interest in Orbit, which he would read for free as a high schooler. The magazine influenced him enough that he quit his high school newspaper when he realized it was simply a mouthpiece for the administration, and started his own publication with friends writing about what interested them. He “borrowed” a few Orbit graphics along the way and printed five issues in all.

But in 1998, St. Mary had his “never meet your heroes” moment when he visited the Orbit offices hoping they would write a review of a film he made. The reception from Vile was less than enthusiastic and St. Mary fumed, telling people, “I don’t understand why this guy is important. Why do people like him?”

Rob St. Mary with a copy of The Orbit Magazine Anthology: Re-Entry. Photo by Nick Hagen.

Several years passed before he saw Vile again, at a 2010 art competition where Vile was one of the judges. He was talking to a friend of Vile and mentioned that he wanted to go back and re-read Orbit to see if it stood the test of time. He also suggested that someone ought to write a history of Vile’s three publications.

A year later, St. Mary was still thinking about the book. Now, he had time and motivation to write it, never mind that he and Vile didn’t hit it off the first time they met. “I knew his magazine was important to me, and that was what mattered most,” St. Mary says.

It took St. Mary about three and a half years to write the book, working mainly nights and weekends while holding down a nine-to-five job. It was named one of 20 Michigan Notable Books in 2016.

St. Mary says Vile’s work shouldn’t be dismissed just because it was profane or juvenile at times. “Vile’s magazines looked at the absurdity of things,” he says. “Satire and humor can sometimes tell a more profound truth than just the truth.”

In other words, honesty might come more easily if you don’t care about angering or upsetting people. “To me, there’s a value to looking at this stuff because it really is part of the cultural evolution of the area,” St. Mary says. “If you really want to understand the cultural evolution of metro Detroit, I think you really have to understand the place alt weeklies and the underground press sit, because they’re often closer to the ground than the dailies.

“I think if you put it all in totality, then you’re going to get a broader sense of what was going on at the time.”