Magazine

Poetry to the People

When he founded Broadside Press in Detroit, Dudley Randall elevated African American voices and changed the face of literature forever.

By Lara Zielin

On an unseasonably warm September evening in 1975, poets, writers, politicians, educators, cultural advocates, and more gathered at Detroit’s Manoogian Mansion to celebrate the 10-year anniversary of Broadside Press. Mayor Coleman A. Young was there, charming staff and guests alike, but the real star of the night was poet Dudley Randall, who had founded Broadside Press and who ran every aspect of it when he wasn’t working his day job as a reference librarian at the University of Detroit (now the University of Detroit Mercy).

Under the leadership of Randall, Broadside Press had published more than 81 titles in the previous decade, nearly all of them celebrating African American poets and their works. By contrast, before Broadside, only 35 poetry books by African Americans were published in the United States from 1945 to 1965.

That evening, lights twinkled and a fresh breeze blew in from the nearby Detroit River. It was a grand night, worth celebrating, since Broadside had changed the face not just of poetry, but of literature writ large. Broadside had “rescued the new Black poetry of the sixties from predictable, white rejection and, furthermore developed an original, highly effective means of get.ting these poems to the national Black community,” wrote June Jordan in a 1974 review of the Broadside book After the Killing.

What’s more, for the first time, black writers were being sought after in major publishing houses, for poetry and more. “Then, Blacks were in the public eye,” Randall said, and the entire landscape of what publishers wanted to acquire—and the mainstream public wanted to read—had shifted.

Who, then, could have predicted that just a few short months later, the press’s deep debt would necessitate its sale? Dudley Randall would fall into a dark depression, burning many of his papers, photos, and documents about Broadside and his own poetry. His legacy would be in jeopardy. Help would come to Randall from a few key sources, including poet and professor Melba Boyd, who worked briefly at the Press beginning in 1972, and who would eventually become his biographer.

Boyd would painstakingly conduct hours of interviews with Randall, recording all the audio, while seeking duplicates of Randall’s correspondence with publishers, poets, and others. She would research historic events and intersect Randall’s life with these important moments. She compiled and organized interviews from Randall’s friends and colleagues. She encouraged him to continue writing, which he did when his depression lifted, publishing A Litany of Friends: New and Selected Poems in 1981. And when Randall died on August 5, 2000, it was Boyd who ensured his collection came to the Bentley. Thanks to her work, Randall’s legacy is preserved, and the collection now showcases his incredible life and his critical role in poetry and in publishing, raising up African American voices at a time when many wanted them silenced.

Finding His Voice

Dudley Randall was born on January 14, 1914, in Washington, D.C., and his parents moved to Detroit when he was six years old. Randall was a quiet, thoughtful child, which he attributed in part to being the son of a preacher. He said he “heard too much talking” at his home in the poor and mostly African American neighborhood of Black Bottom in Detroit. He turned to inward reflection and began writing, publishing his first poem in the Detroit Free Press at age 13.

After graduating from Eastern High School, Randall got a job in 1932 at the Ford Foundry, working for 50 cents per hour in the blast furnace unit at the River Rouge Plant. In 1935, he married his first wife, Ruby Hands, and the pair eloped, certain that Ruby’s parents would disapprove of the union (she was 16; he was 21). The pair settled down in Black Bottom, and Randall began writing poetry when he wasn’t working.

His poem “Hastings Street Girls” about young women searching for excitement on the streets of Black Bottom was soon accepted for publication in Opportunity Magazine, but the magazine folded in 1937 before Randall’s work could be showcased. “There was a dire lack of publishing opportunities for black poetry,” writes Boyd in her Randall biography, Wrestling With the Muse, “and this delayed Randall’s publishing debut.”

But 1937 would still be a milestone year, because that’s when Randall met Robert Hayden—a poet who also grew up in Black Bottom, and who would go on to study under W.H. Auden at the University of Michigan and become the first African American to be appointed as Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress (now known as U.S. Poet Laureate). But back in 1937, he and Randall were just young men meeting in a YMCA to discuss and critique each other’s work, and to socialize occasionally at local clubs

Randall’s relationship with Hayden would continue throughout his life, and, much later, Hayden gave many of his poems to Broadside Press for publication. But numerous milestones came first, including divorce for Randall and marriage to a new wife, Mildred Pinckney, in 1942. World War II also intervened, sending Randall to the South Pacific through the Army Air Corps. He worked as a supply sergeant, and in this role, Boyd writes, his “talent for classifying and cataloguing foreshadowed his future career as a librarian.”

When he returned to Michigan, Randall went to college at Wayne State University on the G.I. Bill, while also working full-time in the Post Office. Randall’s poetry flourished while he was in school, and his subject matter reflected his own musings on the Great Depression and war, as well as increasing racial tensions in Detroit with the surge of African Americans into the city after the war, and continued racial dis.crimination in the automotive plants, as well as by the police.

In 1949, he earned his bachelor’s degree from Wayne, followed by a master’s degree from the University of Michigan in library science in 1951. After graduation, he and Mildred moved to Lincoln, Missouri, where Randall worked at Lincoln University as a librarian.

It was while he was in Missouri that his hometown neighborhood of Black Bottom—which housed more than 300,000 African American residents—was razed by Mayor Albert Cobo and the all-white Detroit city government. The fallout from the mass gentrification project would provide fuel for the Detroit Uprising in 1967, which would further inform Randall’s poetry and Broad.side Press. Around this same time, Randall published one of his most famous poems, “Booker T. and W.E.B.,” which imagines a conversation between Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. Du Bois.

The poem, says Boyd, was “written on the eve of the Civil Rights Movement. In [it], the voice of Du Bois supports the struggle for desegregation and equal rights, while Washington’s retorts represent conformity and acquiescence to conventional racial roles…In the poem, Du Bois gets the last word, which indicates [Randall’s] agreement.”

By 1956, Randall was back in Detroit. He and Mildred had divorced, but he soon met his third wife, Vivian Spencer, on the tennis court at Northwestern High School. They married in 1957 after Randall got a job at the Wayne County Federated Library System as the head of reference in the interlibrary loan department.

He began to write more and more poetry, and was published in magazines such as Free Lance, and the Negro History Bulletin, but his outlets were limited. In his Bentley collection, the earliest rejection letters from publishers date from this time, including a 1957 letter from McFadden Publications in New York for their magazine, True Love. Though there’s no record of the work he submitted, the rejection is boilerplate language that sounds like many of the other “thanks but no thanks” letters he would receive in time from The Atlantic, The New Yorker, the Motown Record Corporation, and many, many more.

Poetry and Civil Rights

On September 15, 1963, a bomb thrown by Ku Klux Klan members tore through the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, killing four girls and injuring at least 14 others. The tragic and racially charged event moved Randall to write “The Ballad of Birmingham,” about a young girl who wants to attend a Freedom March, but is persuaded by her mother to instead go to the “safer” venue of church, where she ultimately loses her life. Soon after, Randall would write “Dressed All in Pink” about the assassination of John F. Kennedy.

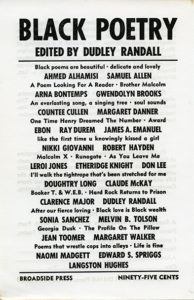

An early promotional flyer for Broadside Press. HS17859

In 1965, both poems were set to music by folk singer Jerry Moore, and Ran.dall wanted a way to copyright his work. Taking 12 dollars out of his library pay.check, he printed them as “broadsides,” and the press was born.

“My strongest motivations have been to get good Black poets published, to produce beautiful books, help create and define the soul of Black folk, and to know the joy of discovering new poets,” Randall said about Broadside in his memoir, Broadside Memories.

While keeping his day job as a librarian, Randall wore every hat possible at Broad.side—acquiring manuscripts, editing them, working with printers, licking stamps, filing, cleaning windows, mentoring young poets, and more. Initially, he had a small collection of volunteers who helped him, though at Broadside’s height, he would employ eight part-time staffers. They worked out of a series of run-down office spaces, including an old burger joint and a former exterminator’s building.

In 1966, Broadside published its first book, Poem, Counterpoem, featuring Randall’s poetry alongside that of poet Margaret Danner. The second book, For Malcolm: Poems on the Life and Death of Malcolm X, was published in 1967, just ahead of the Detroit Rebellion.

The Rebellion launched Broadside into the public sphere. “The intensity of nationalist activism and political radicalism attracted an audience for Black literature,” wrote Boyd in Muse. “Collectively, the new black poets brought an excitement that attracted a broader audience.”

Broadside books flew off the shelves at Vaughn’s Bookstore in Detroit. Black Studies courses at colleges and universities across the United States ordered titles. Broadside published internationally in Europe, Africa, South America, and more. Randall tried to limit himself to four books per year, but found he couldn’t, given all the demand.

The long list of poets on Broadside Press’s pages nearly defies belief and includes Robert Hayden, Gwendolyn Brooks, Sterling Brown, Naomi Long Madgett, Don L. Lee (now Haki Madhubuti ), Langston Hughes, Audre Lorde, and countless more. By 1972, Broadside had published more than 192 authors, either in individual books, anthologies, or in broadsides. Haki Madhubuti alone sold more than 100,000 copies of his work.

Poet Laureate of Detroit

It was in 1972 that a young Boyd met Randall and began working for Broadside Press as an assistant editor, having just completed her master’s degree in English from Western Michigan University. She would help plan the 10-year anniversary celebration at the Manoogian Mansion in Detroit, and would also have insight into the pitfalls that kept Randall and Broadside Press from being profitable. This included his self-admitted Depression-era mentality, for example, that viewed business success as a negative, as well as his penchant for publishing anything he felt was “good,” versus what might actually sell.

By the end of 1975, Broadside Press was $30,000 in debt to its printer, and had uncollected debts from bookstores and poets who owed the press money but were unable to pay. In January 1976, Randall took early retirement from his librarian position at the University of Detroit Mercy to try and fix the red-lining financials, but eventually he was forced to sell the business to the Alexander Crumwell Center.

“His self-image was severely distorted by a sense of catastrophic failure,” Boyd writes, noting that Randall withdrew from friends, and also stopped writing. In January of 1980, deep into his depression, he sat on his bed and placed the barrel of a shotgun next to his head. It was only his wife Vivian’s dis.covery of him in this position that kept him from pulling the trigger.

Slowly, bit by bit, Randall began to emerge from his depression. He started writing again, struggling at first, and then in a flurry: From April 1980 to May 1981, he composed more than 29 poems. He also asked Boyd to be his official biographer.

Broadside Press also welcomed him back as a consulting editor, and he ultimately regained control of the press in 1981. His first publication was Boyd’s book of poetry, Song for Maya.

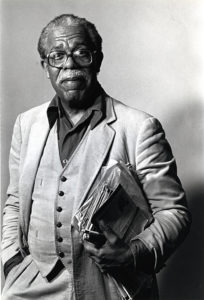

Dudley Randall. HS17867

This was the beginning of an upswing that saw Randall recognized for his many accomplishments in literature. On November 5, 1981, Detroit Mayor Coleman Young named Randall the Poet Laureate of Detroit. In 1986, he was the recipient of the National Endowment for the Arts’ Lifetime Achievement Award. That same year, Wayne State awarded him with an honorary doctorate of letters, and in 1987, the University of Michi.gan gave him a distinguished alumni award.

Although Randall ultimately had to sell Broadside Press a second time (on this occasion to Don and Hilda Vest), he didn’t sink too far into darkness, and was able to publish A Litany of Friends about his depression and emergence from it.

Boyd, meanwhile, worked on a documentary about Randall titled The Black Unicorn: Dudley Randall and the Broadside Press. It debuted at the Detroit Institute of Arts in 1996. Randall was there on its opening night, which also marked his 82nd birthday.

Randall died on August 5, 2000. Boyd published Wrestling With the Muse in 2003, honoring Randall’s request that his biography only come out after he was gone.

Boyd says she worked to make Randall’s voice “primary” in the biography, and her role was to provide context. “I’m not of the school that I knew more than they did,” she says.

Boyd donated Randall’s papers to the Bentley in 2016. His collection is open to the public.