Magazine

Pride and Prejudice

Jim Toy stood on the front lines of the gay rights movement in its earliest days, when physical harm, arrest, and harassment were par for the course. At the age of 85, the equality pioneer donated his papers to the Bentley, showcasing years of perseverance that changed the face of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and well beyond.

by Robert Havey

When Jim Toy entered the small basement of St. Joeseph’s Episcopal Church in Detroit in December 1969, he felt nearly paralyzed with both excitement and fear. He and a few other men and women were meeting to form the Gay Liberation Front of Detroit, the first gay rights organization in Michigan.

It can be difficult to imagine now, but meetings like this where potentially very dangerous for the participants. Sitting down on a folding chair in that church basement, Toy was outing himself as a gay man, putting himself at risk of being ostracized, jailed, or worse. But excitement was in that room as well, because Toy was there at the start of a political and social movement that would transform the entire country.

Disturbing the Peace

“Growing up in an Ohio village in the 1930s and 1940s, I felt totally alone,” Toy says. Homosexuality itself wasn’t quite a crime during Toy’s adolescence, but it might as well have been. Police in many cities (including Ann Arbor) would regularly arrest patrons of gay bars and charge them with the euphemistic crimes of “public indecency” or “disturbing the peace.” Until 1973, homosexuality was regarded as a mental disorder by the American Psychiatric Association, appearing in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders alongside depression and schizophrenia.

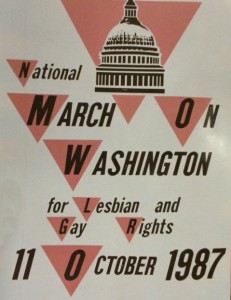

Toy helped organize a March on Washington in 1987, the original flyer for which is in his collection at the Bentley.

In December 1969, resentment of ill treatment by the police came to a head when riots broke out after a raid on the Stonewall Inn in New York City. This bar in Greenwich Village, frequented by the gay community, was often a target of police raids, but this night was different. A crowd of hundreds gathered as patrons were loaded into police cars, shouting and jeering. Soon a full-scale, two-day riot broke out, resulting in the arrest of dozens of people. News of the melee quickly spread around the country. The Stonewall Riots proved to be the clarion call for the gay rights movement.

Around the same time, Toy was surprised to see a notice for the “Gay Meeting” tacked on the bulletin board of his church. Toy had been the organist for the church since 1957, and was used to the radical politics in which the members and staff were involved, but any frank discussion of homosexuality was new. Toy talked with the church priest, asking what the meeting was and if they were even allowed to hold it in the church. Toy recalled the priest’s reply in a 2011 Huffington Post article: “If we can’t have a gay meeting here—whatever a gay meeting is—we might as well shut this God Box down.”

Toy and the others founded the Detroit Gay Liberation Movement on January 15, 1970. A month later, Toy came to Ann Arbor to start a Gay Liberation Front branch. His commitment to the cause was complete. In a speech at an anti-Vietnam War demonstration in Detroit, Toy became the first person in the state of Michigan to publicly come out as gay. There was no turning back.

Organizing, Aligning, Ignoring

The real work soon began. Turning political willpower and angst into tangible results required countless meetings to set priorities, form committees, make contacts in the community—in other words, to organize. The leadership determined early on that the Ann Arbor Gay Liberation Front (AAGLF) should ally with other left-leaning political movements, particularly Civil Rights and feminist groups. Toy himself marched with Martin Luther King Jr. in Detroit in June 1963.

Toy’s work was primarily focused in Ann Arbor, but without any official University of Michigan sanction. In 1971, the AAGLF wanted to host a statewide conference and applied for space. Their request was denied in a letter sent from the office of University President Robben Flemming, citing the need for additional “police presence” on campus. The conference went forward anyway after the vice president of the student council volunteered the keys to the Student Activities Building.

Things might have ended there, as the administration sent an anonymous representative to the conference in secret to report on this burgeoning political movement. A warning of trouble from this person would have surely doomed the group to exile from campus. Toy later said the report described the meeting as “low numbers, low energy. If you ignore this group, they’ll go away.” As a result, Toy was soon able to secure space in the Michigan Union for an official student organization, the Human Sexuality Office.

The Accumulation of Small Changes

Now called the Spectrum Center, the Human Sexuality Office opened in September 1971. It was the first organization of its kind not just at U-M, but the whole country. Its beginnings were very humble. Toy and his co-founder, Cynthia Gair, were given quarter-time appointments as program advisors and crammed into a tiny room with just two desks and four chairs. Since there was no model to follow with an organization of this kind, everything had to be done from scratch. Outreach and peer counseling were obviously priorities, but gay rights advocacy and community organizing were also crucial.

Toy and Gair worked on many fronts to dispel myths and stereotypes of homosexuality. They gave talks, offered classroom presentations, and organized “consciousness-raising” sessions for University units that were involved directly with gay students, such as University Health Services and resident advisors. At one point, Toy’s office housed a 24-hour “gay hotline” for troubled students to call should they need emergency counseling.

Toy’s collection features images of protests, including this one in Ann Arbor in 1985. (Bentley image HS15020)

The AIDS crisis in the 1980s and ’90s put the organization to the test. The disease was claiming thousands of lives while the social backlash threatened to undo all of the progress the gay rights movement had made. Lines of communication to members of the gay community proved to be invaluable, providing informational flyers to bars, churches, and student groups. The political influence allowed them to combat radical, unhelpful plans proposed by anti-gay legislators, including one proposal to quarantine all people who were HIV-positive.

With homosexuality becoming more and more socially accepted in society, Toy began to focus on political change. He started small, lobbying U-M to amend anti-harassment bylaws to cover sexual orientation. After success at the University, Toy helped implement anti-discrimination laws in several towns and cities in Michigan, including Ann Arbor, Dearborn, and Detroit. Small, methodical legislative changes kept accumulating.

In 2004, Michigan voters passed a constitutional amendment to ban same-sex marriage. Seemingly a devastating blow to gay rights advocates, Toy was not flustered. He said in an interview published in a community center newspaper that he was “disappointed, but not surprised.” He had encountered vehement resistance to his ideas in the past and knew that this wasn’t the end of the fight. Instead of stewing in defeat, Toy redirected energy back to non-discrimination policies, health care for transgender youth, and adoption rights.

Michigan’s anti-gay marriage statute was struck down by the Supreme Court in 2015. Even without this ruling, it’s very possible that the amendment would have been repealed before too long. Support for gay marriage has surged over time, representing not just a generational change, but people changing their minds on the issue writ large. The patience shown by Toy and other activists has paid off.

At age 85, Toy is still working, still giving interviews and talks to audiences around the country. Inevitably, he is asked to reflect on his life’s work, to pick an achievement that he is most proud of. He brings up his time counseling young gay people. “Hearing years later from people who were clients of mine that have said, ‘If it hadn’t been for you, I’d have killed myself.’ It’s not pride, but gratitude. I’m grateful I had the opportunity.”

Note: Jim Toy passed away in 2022, leaving behind a remarkable legacy of activism for equality that changed the lives of many.