Magazine

“Problem Pregnancies” and Historical Access

Archived papers at the Bentley show how U-M counseled women on their reproductive options in the early 1970s, prior to Roe v. Wade.

by Jenn McKee

On June 24, 2022, the day the U.S. Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, U-M President Mary Sue Coleman sent out an email to the campus community that read, in part, “Today’s Supreme Court ruling on the right to an abortion will affect many on our campus and beyond. I strongly support access to abortion services, and I will do everything in my power as president to ensure we continue to provide this critically important care.”

Navigating how to support women in this moment is complicated, but the University could take a page from its past.

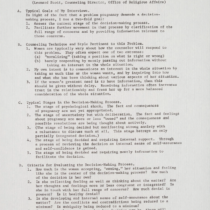

Documents at the Bentley reveal that in 1971, counselors affiliated with U-M’s Religious Affairs Office discussed unwanted pregnancies with women, and if these women wished to explore abortion, they were given information about two vetted clinics in New York, a state where abortion was legal.

Though it may seem surprising that local clergy led the way in providing students with this information, a 1971 letter from counseling director Leonard Scott to the physician father of two male U-M students elucidates Scott’s journey through this complicated moral terrain.

“I suppose as long as some of the public wants abortion, and as long as physicians will provide abortion, abortion will remain a reality even for those of us who cannot approve of it on any grounds,” Scott wrote. “But even those who choose abortion nevertheless are thinking human beings who deserve our professional concern.”

Rianna Johnson-Levy, a doctoral student in U-M’s joint program of history and women’s and gender studies, has studied these archived materials extensively, including Scott’s approach to services.

“There are several pamphlets from Scott about how he conducted problem pregnancy counseling, and it really was counseling that had no obvious conclusion,” she says. “Everyone was searching in this moment. It was individuals grappling with their own beliefs and trying to figure out what felt right to them.”

Perhaps inevitably, counselors and medical staffers worried about the legal (and insurance-related) ramifications of counseling students about abortion. Some were members of the Michigan Committee for Clergy Counseling on Problem Pregnancy, a consortium of more than 75 Michigan ministers who set up services and even a telephone line to help counsel women with unwanted pregnancies.

“Exactly when this is happening, multiple members of the Michigan Committee for Clergy Counseling on Problem Pregnancy were arrested and raided and wiretapped,” says Johnson-Levy. “Everything U-M did was on the up-and-up, but a lot of these same figures, in their outside-of-Michigan work, it’s clear, were really taking a huge legal risk.”

Pregnancy counseling practices and legal issues were discussed and debated at U-M prior to the 1973 Roe v. Wade ruling, which made abortion legal, and which was recently overturned.

An archived 1969 letter from Detroit attorney Lloyd A. Semple to a Grosse Pointe clergy member reads that “it is our opinion that it is illegal to counsel abortions to be performed in Michigan for reasons other than to save the physical life of the woman.” But he agrees that “counseling Michigan women to have abortions in other jurisdictions” would be legal if “the abortions were committed in jurisdictions where the abortions were legal.”

U-M counselors pointed students to two clinics in New York—Women’s Services, and Eastern Women’s Center, both of which were visited and thoroughly evaluated by a team from U-M.

Archived documents explain procedures, costs, transportation, and instructional details such as, “Go to TWA ticket counter, upper level, and look for a woman wearing a pink smock, carrying a clipboard . . . . There are no men picking patients up at the airport. Go only with the woman counselor.” (This instruction was spelled out in a 1972 campus memo from Scott to “Problem pregnancy and abortion counselors.”)

One reason counselors likely felt they had to highlight trusted clinics was that sketchier ones were, at the time, frequently advertising in The Michigan Daily.

“The abortion clinics in New York that were advertising were generally for-profit ventures of dubious quality, and there are a lot of accounts of people getting hurt at these clinics,” says Johnson-Levy. “And part of the concern of the counseling department was that there was no counseling that went along with this. So they were also concerned with the emotional well-being of students.”

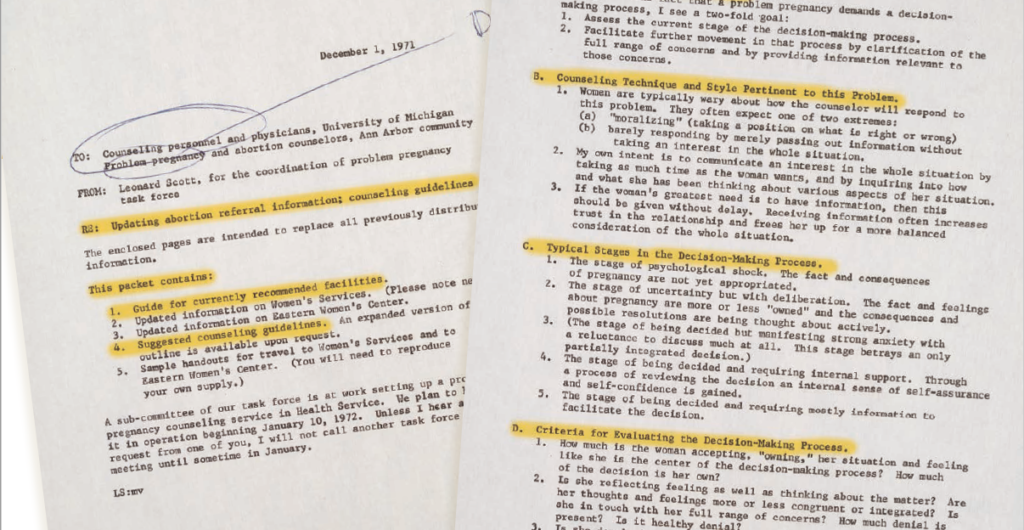

Indeed, in a 1971 counseling packet issued by Scott, he spelled out his “Counseling Technique and Style Pertinent to this Problem,” wherein he explained that women are often wary of counselors who moralize or just hand out information.

“My own intent,” he wrote, “is to communicate an interest in the whole situation by taking as much time as the woman wants, and by inquiring into how and what she has been thinking about various aspects of her situation.”

Scott echoed this notion in his letter to the physician father who found fault with U-M counselors sharing information about abortion. “I find I cannot answer some of your questions,” Scott wrote. “ . . . Only those women and couples who are directly involved can answer the embryological, religious, and ethical questions you raise . . . . They must speak for themselves.”