Magazine

Seeing Stars Through the Clouds

For both astronomers and the public, predicting the weather was long an impossible dream. That is, until U-M’s Detroit Observatory trained a man who created something revolutionary: the weather forecast.

By Andrew Rutledge

Cleveland Abbe was worried.

It was September 1, 1869, and Abbe was waiting for telegrams at the Cincinnati Observatory. It was the first day of his revolutionary new program that used a network of observers across the Ohio Valley to report on weather conditions in their areas.

By using the telegraph to collect meteorological reports from a vast area nearly instantaneously, Abbe could create the most accurate daily picture of the weather ever in the United States. Nothing like it had been attempted before.

He had arranged for 40 observers but, as the hours passed, no messages arrived. By nightfall, it looked like the program might be over before it started. Until—finally— there was one. Then another.

Two messages were enough for Abbe, who boldly issued his first weather report the next day. It was the first such report in American history.

Abbe Looks Up

Abbe was born in New York City in 1838. An excellent student of mathematics and chemistry, he knew by the time he was a teenager that he wanted to make a career studying the stars. After he graduated from the Free Academy (the future City University of New York) in 1857, he wrote to every astronomer in the nation seeking a position and training.

Franz Brünnow, the first director of U-M’s own Detroit Observatory, wrote back and encouraged Abbe to come to Michigan, though he could not pay him. Abbe didn’t hesitate.

Once in Ann Arbor, Abbe supported himself by teaching engineering at U-M and the Agricultural College of the State of Michigan (now Michigan State University). But he spent all his free time studying astronomy at the Detroit Observatory. In 1860, a restructuring of U-M staff eliminated his position, forcing him to leave Michigan in search of work.

Abbe spent the following years seeking every opportunity to study astronomy he could find, even spending two years as a “supernumerary astronomer” at the Russian Imperial Observatory near St. Petersburg. In 1868, Abbe was offered the position of director of the Cincinnati Observatory, but there was a problem: The Cincinnati Observatory was bankrupt.

Undeterred, Abbe thought he might see a solution by solving a different astronomical challenge: predicting the weather.

Weather or Not

Astronomers have always worried about the weather. After all, from the time humans first looked skyward, they couldn’t see the stars if it was cloudy.

By the 1800s, astronomers’ understanding of how weather impacted their studies had expanded dramatically. Among their most important discoveries was that the viewing would be poor when the temperature changed, even if the skies were clear.

Light travels through hot and cold air at different speeds. When a cold front mixes warm and cold air, the mixed air causes light to bend—just like when light travels through water. As a result, objects seen in a telescope appear blurry or even in the wrong place entirely. Thus, when planning their studies, astronomers needed to know what the weather and temperature would be as precisely as possible.

Predicting the Rains

While at the Detroit Observatory, Abbe had been “impressed with the unsatisfactory state of our knowledge of atmospheric refraction” and its impact on astronomy. And so when he arrived in Cincinnati, he was convinced that with “a proper system of weather reports much could be done for the welfare of man, and astronomy also could be benefited.”

Abbe came up with an idea. In return for donations, he would create a network of observers who would send him daily telegrams reporting the local temperature, rainfall, and cloud cover. Even more ambitiously, he would use those reports to not only summarize the weather but also predict what it would do next. In particular, he promised to provide notices of weather that would impact travel and warn farmers of floods or frost.

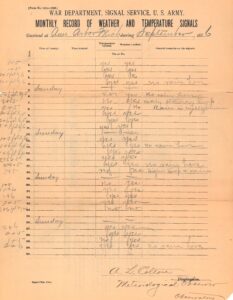

The Observatory created daily weather records as a volunteer weather station for the Weather Bureau, which was then housed under the Army. Image source: University of Michigan Detroit Observatory records

Donations poured in and Abbe launched his program on that nerve-wracking day in September 1869. Despite its slow start, an average 33 messages soon began arriving daily, steadily increasing the accuracy of his predictions.

With Abbe’s success, businesses around the country pressured Congress to create a similar national system. A bill quickly passed through Congress and was signed into law in early 1870. With that, the precursor to what would eventually become the United States Weather Bureau was created.

Abbe was brought in as chief meteorologist of the newfound national weather service and expanded his system across the eastern United States. Receiving daily telegrams from hundreds of observers, the agency published a “Weather Synopsis and Probabilities” three times a day. These began with a brief overview of conditions nationwide followed by the “probabilities” for future conditions. For example, on March 2, 1871:

Probabilities. Threatening and rainy weather will probably be experienced on Friday on the Atlantic and Lower Lakes, with fresh winds. Brisk winds on the Gulf and Upper Lakes, with clear weather in the Northwest.

At its height in the 1880s, 541 observation stations across the U.S., Canada, and the Caribbean provided detailed daily reports and forecasts to all 38 states. As the weather service’s leader, Abbe soon earned the nickname “Old Probabilities.”

The weather bureau’s forecasts were distributed by telegraph to all weather stations, which were required to print copies for display at their local post offices.

Forecasts were also spread using flags flown from prominent buildings in towns across the nation. One such building was the Detroit Observatory, thanks to its third director, Mark Harrington.

A leading meteorological expert himself, Harrington provided daily weather observations and displayed weather flags from a pole mounted on the Observatory’s roof for the benefit of students and Ann Arborites. The Bentley has a massive collection of these daily reports, documenting the history of weather in Michigan.

Harrington would later become the head of the newly renamed Weather Bureau in 1891.

The Detroit Observatory continued submitting daily weather reports and posting warnings until the 1930s. Today, the Weather Bureau continues its work as the National Weather Service. At U-M, the study of the weather is no longer a focus of astronomers, but the Department of Climate and Space Sciences and Engineering conducts research on meteorology and climate change.

[Lead image: In 1868, the Observatory had a roof-mounted anemometer to measure wind speeds and a pole that would eventually display weather flags. BL001679]