Magazine

Soldiers and Warriors

Among the 20,000 American Indians who fought for the Union and the Confederacy during the Civil War, a single company from Michigan was made up almost entirely of indigenous men. A researcher used Bentley archives to trace their history and share the story of the Anishinaabeg of Company K.

by Katie Vloet

Would they be loyal Union soldiers? Should these “savage warriors” be relied upon as allies? This was the cultural backdrop on the day in May 1864 that Company K of the First Michigan Sharpshooters fought Confederate soldiers for the first time in the smoky, burning thicket of the Battle of the Wilderness— the beginning stage of General Ulysses S. Grant’s offensive in Virginia.

According to his comrades, Private Daniel Mwakewenah killed 32 enemy soldiers during the battle. Sergeant Thomas Kechittigo convinced soldiers to camouflage their uniforms with mud and leaves. First Sergeant Charles Allen was wounded, resulting in his death at a Fredericksburg Hospital two weeks later.

Loyal? Trustworthy? Indeed.

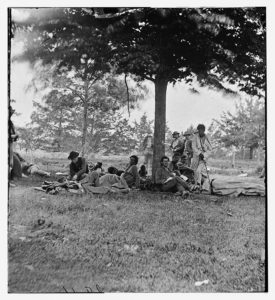

Wounded American Indian soldiers in May 1864 after the second battle of Fredericksburg.

“After statewide speculation on whether Michigan Indians would make good soldiers, the Anishinaabeg of Company K proved to their white officers and the audience at home that they were loyal Union men and effective soldiers,” Michelle Cassidy writes in her dissertation about the American Indians who joined Company K.

Cassidy, now an assistant professor of history at Central Michigan University, was inspired to write about the Anishinaabeg (Ojibweg, Odawaag, and Boodewaadamiig) and their role in the Civil War while researching a graduate student project at the Bentley Historical Library. Her research evolved into her

doctoral dissertation at U-M, “Both the Honor and the Profit: Anishinaabe Warriors, Soldiers, and Veterans from Pontiac’s War through the Civil War.” While she conducted research at many other libraries and institutions, the Bentley served as the home base for her work.

Much has been written about the 20,000 American Indians who fought for the Union and the Confederacy, though most of it has focused on men from the western United States. Cassidy tells the story of the 139 indigenous men, along with seven Euro-American men, who served in Company K. Most were Odawaag and Ojibweg from Michigan’s Lower Peninsula. “(T)hey stood out as a separate unit, which was unusual for a company outside of Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma),” Cassidy writes.

Among the collections that brought her dissertation to life were the Peter Dougherty Papers at the Bentley, which consist of reports by two Presbyterian missionaries who worked with the Anishinaabeg around the Grand Traverse and Little Traverse Bay regions of Northern Michigan. From these papers, she learned about Daniel Mwakewenah, the private at the start of this article, as well as others who fought in Company K. The George Nelson Smith Papers at the Bentley also provided valuable information about who enlisted in the Union army and why. “Materials at the Bentley stressed the complex history of Company K men and their perceptions of self that could encompass the identities of a warrior, soldier, hunter, farmer, Christian, citizen, band member, and Anishinaabe,”

Cassidy says.

Cassidy’s work highlights not only this complex history but also the knotty relationship between American Indians and the U.S. government and other leaders at the time. “Company K became Union soldiers at the same time government policies concerning indigenous peoples—especially west of Michigan—focused on reservations and policies of removal and containment,” she writes. “It is striking that the United States armed certain Indian men at the same time it disarmed others.”

The Anishinaabe soldiers who fought in the Civil War knew that the experience could help to strengthen their claims of citizenship. “The Anishinaabe strove for a dual citizenship that would provide the rights and protections associated with state, and later, national, citizenship,” Cassidy writes, “while also claiming Indian status and determining the political, social, and religious practices of their communities.”

Their efforts had mixed results. Many faced enormous land losses and experienced “social and political degradation,” Cassidy writes. Land ownership and claims to citizenship did not lead to a secure or respected place in Michigan, she writes, because of racial prejudice and unscrupulous people who took advantage of them. “Despite their military service, Anishinaabe veterans remained vulnerable to land fraud due to poverty and their Indian identities.”

Even so, their efforts had some positive and lasting effects. The presence of the Anishinaabeg in the state of Michigan today, including 12 federally recognized tribes, “is a testament to Anishinaabe strategies, which includes the military service of Company K,” Cassidy says.

Each of the collections that Michelle Cassidy used in her research is open to the public.