Magazine

The Battle for the Heavens

When U-M’s president and its Board of Regents decided to build a coal power plant to fuel a growing campus, its campus neighbor, the Detroit Observatory, fought to keep the skies clear of black smoke. Letters between the warring factions show the tension between a burgeoning campus and faculty who were desperate to save their research.

by Robert Havey

In 1912, on a creaking ship bound for Argentina, U-M Professor and Director of Astronomy William J. Hussey (pictured above) read a letter from the Board of Regents informing him that a power plant was to be constructed less than a mile from the University’s own Detroit Observatory.

Within months, one of the best observatories in the nation was to be beset by plumes of coal smoke that would block sight lines of the telescopes, clog instruments, and otherwise ruin the exacting measurements required for astronomical research. At least Hussey felt this was the case.

His reply to U-M President Harry B. Hutchins—penned when Hussey reached La Plata, a sister city to Buenos Aires and the location where Hussey would be researching dual stars for the next few months—was scathingly direct. He condemned the “great mistake” President Hutchins and the Board of Regents were making, blasting not just “the disastrous effect which it will have on the Observatory” but also the damage the plant would have on “a considerable number of innocent people of Ann Arbor.”

The letter set off a chain of impassioned correspondence on both sides. The notes sent from Ann Arbor to South America and back again, from regent to regent, and from Hussey’s wife to Hutchins, highlight the tension between the inexorable expansion of a growing University, the reach of its administration, and the particular needs of its faculty researchers. The stage was set for an epic battle between the forces of progress against the protectors of tradition, all revolving around a small building on an isolated hill on the outskirts of U-M’s burgeoning campus.

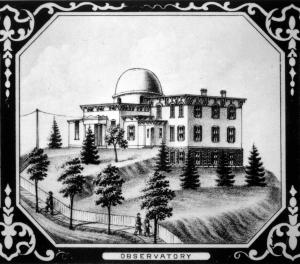

Early drawing of the Observatory

A State-of-the-Art Observatory

At the time, the Detroit Observatory was the cornerstone for scientific research at the University of Michigan. The Observatory was built in 1854 when the U-M’s first president, Henry Philip Tappan, wanted to transform Michigan from a small Midwestern liberal arts college into an elite research university.

Tappan secured funding for the Observatory from major donors in Detroit (hence the name). A site was chosen on a remote hill northeast of campus. Tappan spared no expense, contracting the world-renowned telescope manufacturer Henry Fitz to grind a lens for a new refracting telescope. When the completed telescope was installed in 1857, it was one of the largest in the world.

Shortly after the Detroit Observatory’s construction, Tappan was able to recruit Franz Brünnow to Ann Arbor to be the first director of astronomy and also the first member of the University’s faculty with a Ph.D.

In the 50 years before Hussey was appointed director, the astronomy department thrived. Measurements made at the Observatory were used to calibrate precise timepieces for local banks and rail stations, making Ann Arbor run on “Detroit Observatory Time.” Faculty members discovered and named more than a dozen asteroids. Brünnow started the University’s first academic journal, Astronomical Notices, in 1858.

Hussey built on all this success as the Observatory’s director, beginning in 1905. He oversaw the expansion of the department from 12 students to more than 100. He secured large donations from his college friend Robert Patterson Lamont for new equipment, including a 371/2-inch reflecting telescope.

He was also deliberately kept out of conversations as multiple sites for the new coal plant were considered.

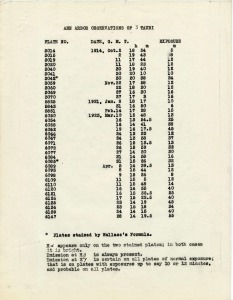

An example of the precise telescope data required for astronomical exploration: Hussey research on a T Tauri star

Grandiose Arguments

Opinions about the plant’s location were solicited from a group of New York engineers as well as U-M’s Dean of Engineering, M. E. Cooley – but not Hussey. Regent William L. Clements wrote that he did “…not feel like accepting altogether as conclusive what [Professor Hussey] would say on the subject.” Instead, the plan was to find “some man other than Prof. Hussey, whose opinion we would all accept as conclusive as the effect of this location upon the Observatory.”

President Hutchins wrote Hussey to reassure him about this decision: “In regard to the location of the heating plant, I am very sure that the regents will not do anything that will imperil the Observatory.”

The plans to move ahead with the plant were approved on June 24, 1912, while Hussey was in the middle of the Atlantic.

The chosen site was a swampy ravine that ran from North University Avenue to the Huron River. It was completely undeveloped with just a shallow pond in the southern end called the Cat Hole. (The origin of the name “Cat Hole” is unknown, but a popular myth at the time held that the name came from a practice that medical students had of discarding their used dissection specimens in the pond.)

The Cat Hole was probably the most logical place to anyone looking at a map of Ann Arbor in 1912. Most of the land west of campus was already developed. The city was growing rapidly and the last empty fields were between the Diag and the river. The Cat Hole was also the site closest to the hospital and therefore would be much more efficient for delivering power.

Perhaps the Board of Regents knew all too well the grandiose arguments Hussey would make in defense of the Observatory. This wasn’t the first time Hussey railed against the encroachment of industry. In 1908, he successfully argued against a proposed road closure that would have diverted traffic right past the Observatory and brought all the accompanying dust, noise, and street lights with it. “The glory of an observatory,” he argued, “is not in being a unique thing to look at, but in the work which it can do. Dust, smoke, and traffic by day, and the arc light by night, are its enemies, and I should be recreant in my duty if I did not attempt to safeguard the site in every way.

“This costly equipment, if it is to serve its purpose, must have the best conditions, for a great observatory should be a pride not only to the University but also the town in which it is located.”

Work at an observatory in 1912 required precision and patience from astronomers. All the instruments were extremely sensitive and needed to be set by hand. The Fitz telescope had intricate clockwork to adjust each axis of its orientation as well as a drive system for the telescope to follow the stars’ subtle motion across the sky. All of this needed to be done in complete darkness while recording every setting and measurement was recorded in a log book, all by hand.

President Harry B. Hutchins

Judges of Men

Ethel Hussey, accompanying her husband on the trip to Argentina, also sent a letter to Hutchins and was unafraid of getting angry and personal in her response to the decision about the power plant. Not waiting for the ship to reach port (her letter was addressed “At Sea, Approaching Rio de Janeiro”), Ethel Hussey’s letter fell just short of accusing Hutchins and the Board of Regents of approving the Cat Hole construction solely out of spite for her and her husband. She claimed, “There are reasons why the Heating Plant went in the Cat Hole, but they are not engineering ones.”

She closed her letter, “As some of you have said, you are not judges of engineering, but you can hardly escape the responsibility of being judges of men, for it was a question of that after all.”

In the end, the power plant was built on the Cat Hole site and Hussey was forced to focus his ambitions on expanding the astronomy department’s reach to the southern hemisphere. The worldwide trend in astronomy was to build observatories on rural mountain tops far away from the polluting light from cities.

Shortly before his death at age 64, Hussey planned to build an observatory in South Africa to continue his research on double stars. He fell ill and died suddenly on a ship to Bloemfontein, South Africa, in 1926. The Lamont-Hussey observatory was open from 1928 to 1972. It was recently converted into the only digital planetarium in South Africa.

The Detroit Observatory eventually fell into disuse as campus flourished around what was once an isolated hill. Research stopped altogether in 1963 when the astronomy department moved to the Dennison Building.

In 1994, U-M President James Duderstadt, along with his wife, Anne, helped spearhead an effort to preserve the Observatory. Renovations began a few years later, restoring the building to its original 1854 condition.

The Bentley Historical Library took over Observatory operations in 2005.