Magazine

The Case of the Missing Mastodon

by Lara Zielin

On a warm fall day in 1934, Works Progress Administration (WPA) workers were laboring in the sun to dredge a pond in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, and construct a stone wall around its perimeter. Suddenly, the mouth of their steam shovel held not just dirt—but bones. Mastodon bones, to be precise.

Ermine Cowles Case, a U-M professor of paleontology and geology, wrote about the find in a 1935 article titled “The Bloomfield Hills Mastodon.” In it, he explained that the mastodon was young, “still retaining the last of its milk teeth” and befell some unfortunate fate at the edge of the pond some 25,000 years ago.

According to Case: “The massive carcass was probably dismembered by prehistoric carnivores, the bones scattered by the elements and interred in the organic layers of marl beneath the calm waters. The eons passed, as they do. Further layers of marl covered and protected the sturdiest of the remains.”

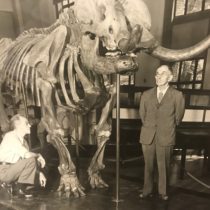

While many of the preserved remains had decayed, broken, or simply degraded, paleontologists were able to take the skull, jaw, ribs, and a few vertebrae back to Ann Arbor. The pieces were cleaned up, “hardened and then reassembled,” according to Case.

But what happened to the remains after that remains a mystery.

By the fall of 1935, when Case wrote his article, the young mastodon was simply…lost. Case acknowledges that the remains were on display for a time at the University Museum, but then went missing. “Last attempts to find them were fruitless,” he writes.

Fortunately, the Ermine Cowles Case papers at the Bentley Historical Library have not suffered the same fate, and in fact they are a treasure trove of paleontology history—including his digs to unearth and name never-before-seen dinosaurs, and his research on prehistoric vertebrates.

This collection is open to the public.