Magazine

The Evolution of Michigan Football

by Greg Kinney

When Irving Pond scored Michigan’s first intercollegiate touchdown in a game against Racine College at White Stockings Park in Chicago in May 1879, U-M students had been playing “football” for more than 15 years. But their game bore little resemblance to what’s played in Michigan Stadium today, or even to the new “rugby football” that Pond and his teammates were playing. Materials at the Bentley tell the story of how football became the sport we know and love today.

During U-M’s formative years, football was a mass game, with as many as 80 players on a side. The October 7, 1876 issue of the student newspaper The Chronicle reported that 42 freshmen defeated 82 sophomores by a score of 5-0. It was also a kicking game, closer to “association football” (soccer) than to rugby football. The two sides squared off on an open field and attempted to kick a ball over a goal line. And the ball was not the only thing kicked: Bruised shins and bloodied noses were common, as were “tumultuous collisions,” as the April 5, 1879 Chronicle reported. Most importantly it was a contest between classes. This version of football derived from an even older tradition: the rush.

Battles, Rivalries, and One Particular Fence

The rush was a sometimes spontaneous, sometimes planned confrontation between classes, especially freshmen and sophomores —- and was often little more than a street fight with no ball necessary. It was a long-standing tradition on many campuses, in some cases dating from the 17th century. At U-M, the rush might take place on campus or in city streets as rival classes faced off. Scratches and bruises were treated as badges of honor, but some combatants were disciplined and a few expelled. An 1875 Chronicle article acknowledged that “rushing is not looked upon with favor by the police.”

The 1874 issue of the Palladium, an early U-M yearbook, illustrates class rivalries with a cartoon that pits inept freshman against skilled sophomores.

When a critic took to the pages of The Chronicle in 1871 to attack rushing as “unbecoming a gentleman” and a stain on the University, a defender of the tradition replied, “A rush is the incarnation of energy in its most playful mood. The spectator must profoundly respect the supreme good-nature and hearty enjoyment in both giving and receiving the severest bruises.” He claimed to have seen “a large representation of the faculty standing at the windows while a rush was in progress below, evidently enjoying the scene.” Class histories in early student yearbooks the Oracle and Palladium recounted the heroic battles and celebrated notable rush “warriors.”

A Michigan variation on the rush was known as “Over the Fence.” For a time the original campus was bordered by a picket fence. The ultimate way to humiliate a class rival was to pick him up and toss him to the other side.

A Pretty Hard Grind

Michigan students were aware that new versions of football were becoming popular in the East, partly in an effort to suppress the rush and also in reaction to the chaotic play of traditional football. Princeton and Rutgers played the first intercollegiate football game in 1869 under rules that resembled those of soccer. Harvard faced McGill University in 1874 under the Canadian school’s version of rugby rules. Variations of the rugby rules soon swept the East.

U-M student Charles Mills Gayley, who learned the English version of rugby football in London and Belfast, tried to introduce the game to his classmates before his graduation in 1878. In the early spring of 1877, The Chronicle published a three-part series listing the 59 essential rules of rugby, noting how they differed from the “chaotic traditions … of the beloved rush” and concluded that “even the dullest aspirant to football honors” could master them.

Football Associations were formed and captains named each year from 1873 to 1878. “University elevens,” as the teams were called, were chosen in 1877 and 1878. All to no avail, as outside games could not be arranged. A campus match under the rugby rules was played on May 17, 1877, and a reporter noted that the boys were catching on to the new game, but that as a spectator, he preferred “the old rushing, shin-kicking rabble.”

Then, in October 1878, a challenge was received from Racine College. The Wisconsin school proposed that a game under the rugby rules be played in Chicago and offered to procure the use of White Stocking Park, tend to all the advertising, and give U-M two-thirds of the gate proceeds. The school also promised to send along a copy of the modified rugby rules.

Michigan had not yet organized a team, certainly not one that understood the rugby rules, and the contest was put off until spring. By late October The Chronicle reported that four bare posts of “mysterious uselessness” had appeared on campus, but few other steps toward preparing a team seemed to have been made. When the Football Association was reorganized in mid-November as a broader Student Athletic Association, The Chronicle urged the new group to select a “football eleven” while the weather was still good enough to allow it “to become familiar at least with the new rules.” The editors warned “that a defeat at the hands of Racine would be a pretty hard ‘grind’” and thought such a loss was “by no means an impossibility.”

It was late April before the Athletic Association finally got a team together and moved the goal posts to a new practice ground near where the Power Center now stands. A committee of three was named to select a team, which then would choose its own captain. Final arrangements for the game were not settled until May 17.

Racine players, meanwhile, had been practicing in their gymnasium for months and even had a team song with the chorus: “The foot-ball now goes round/The sides begin to kick/Ann Arbor’s team will surely see/Our men are awful quick.”

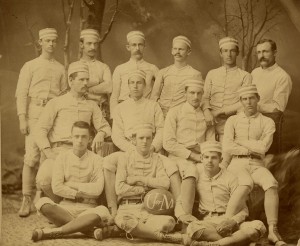

Finally, game day arrived on May 30, 1879. It would be the first intercollegiate football game west of the Allegheny Mountains. Irving Pond scored his touchdown on a long run, and Michigan’s fans erupted with cheers of “Pond forever.” It was captain David DeTar’s subsequent “kick for goal,” however, that gave the Wolverines a 1-0 victory (no points were awarded for touchdowns, only goals kicked). The captain led a triumphant return to Ann Arbor, and a team photo was taken at the Revenaugh Studio.

Class Rivalries Evolve

The May 8 Chronicle noted that “the Rugby game has entirely supplanted the old method of playing foot-ball. A good change, as the [r]ugby game is more scientific and requires more head-work than the old game.” The old game didn’t just disappear, however.

The 1879 U-M football team had their photo taken at the Revenaugh Studio after their win over Racine.

While the rush, at least in its more violent forms, was gradually suppressed and replaced by milder forms of hazing, and “Over the Fence” disappeared along with the campus picket fence in 1890, the old-style football morphed into “pushball.” Upwards of 100 men on a side would attempt to push a giant inflated ball over the opposing class’s goal. Pushball would remain a staple of class day competition into the 1920s, along with tug-of-war, wrestling, obstacle courses, and other contests. Classes would march down State Street, sometimes with their own bands, ready to defend their honor.

Meanwhile, Rugby Football Becomes Football

Football would also continue to evolve. Regions and schools adopted their own versions of rugby rules. A series of innovations and rule reforms led by Walter Camp of Yale included the notion of a line of scrimmage, three downs to make five yards, and more. With each change, the game diverged from its rugby football roots and became simply football — an American college game.

Michigan scored wins over Toronto in the fall of 1879 and again in 1880. In 1881, a long-cherished student dream came to pass. Michigan traveled east to play against the big three: Harvard, Yale, and Princeton. The 14-man Wolverine squad played three games in five days. They lost all three, but played well enough to show that western football — and Michigan football — was on the rise.