Magazine

The Long View

Esteemed film editor Jay Cassidy’s gift of 5,000 photos to the Bentley brings to life the turbulent, defiant, electric period of the late ’60s.

By Katie Vloet

Through Jay Cassidy’s lens, the era of the late ’60s was a kaleidoscope of fervent war protests, a grinning Robert F. Kennedy just three weeks before his assassination, counterculture, radicals, and riots.

It was also a time of The Doors at the IM Building, the football team upsetting Ohio State, and students kissing under the Diag Arch. It was Kurt Vonnegut and Joan Baez and Allen Ginsberg.

Cassidy – now a three-time Academy Award-nominated film editor – first gave about 50 of his photos to the Bentley, along with pictures given by other former Michigan Daily staffers, in 2007.

He discovered that “my negatives were in very good shape. The envelopes that were holding them were not,” recalls Cassidy (’70). “I hadn’t done anything to preserve them.”

He decided to give them to someone who would. In 2010, he added the remainder of his Daily photographs to what would become the Jay Cassidy Photograph Collection at the Bentley – some 5,000 images in all. The Bentley has archived the photos and created a searchable online database that can be accessed by historians, researchers, and the general public.

Cassidy is pleased that the material has been made broadly available, rather than staying hidden in non-acid-free envelopes inside storage boxes at his house. In the 44 years since he graduated from U-M, Cassidy has been the editor of more than 40 films, notably American Hustle and Silver Linings Playbook. He collaborated with Sean Penn on Into the Wild, as well as all the other films Penn has directed. But he still is aware of the formative role that his Daily career played in the development of his vision of the world, especially given the tumult of the period. The world was electric, and he was on the front lines – both as a student at a university with a strong leaning toward activism, and as a photojournalist.

“The great thing about the Daily at that time is that it was a forum for the process of questioning,” he says. “It was raising its voice on issues that were a little difficult for the U to deal with.”

Student protests dotted the campus. “It was a time of an unraveling of society’s belief in what they were being told by the government,” he says.

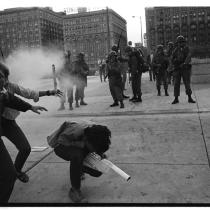

His Daily assignments took him off campus, such as his assignment to cover the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago. “Everybody felt the tear gas,” he says, recounting one of his images that is most emblematic of the time period. In it, a cloud of tear gas rises in the air next to a group of protesters. Dan Biber (’71) is pictured kneeling after National Guard members sprayed tear gas directly in his face, The Michigan Daily reported at the time. “No reporter in Chicago last week could have avoided being sickened by the whole damn mess, the bastardization of democracy and the disregard of human rights,” Daniel Okrent (’69) – who would go on to become an award-winning author, historian, and editor – wrote in the Daily at the time.

“It was quite a stressful experience to go through,” Cassidy says, adding that he still remembered the feeling of profound discomfort when he looked through the photographs years later.

He photographed Robert F. Kennedy’s visit to Detroit – Kennedy shaking hands with supporters, Kennedy with a toothy grin. Such a happy day, such a positive energy – yet Kennedy was to be assassinated just a few short weeks later. “This was a slice of his life; he had no idea that it was all going to be gone in a couple of weeks,” Cassidy says. “That’s one of the photographs that really moved me, looking back. There’s something very poignant about it.”

Another set of images that caught his attention all these years later involved his coverage of the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) meetings. At the time, he saw rooms full of revolutionaries. Later, he saw them differently. “Everyone was just a baby,” he says. The passage of time “makes you look at it all from a very different perspective.”

When he was a student, Cassidy was conscious of the fact that he was learning and working during an exceptional period in the nation’s history. Even so, he did not see each frame, every contact sheet, as something precious or valuable.

“At the Daily, you take all these pictures, and you barely look at them; you run one, then throw the rest in the envelope,” he says. “With the majority, I looked at them once and didn’t consider anything other than the obligation at the moment.”

Cassidy hopes that his donation helps to remind people that archives are dynamic things, always being added to, rather than unchanging collections. And he points out that a person’s estate isn’t the only source of archival material for libraries; other living people can donate, just like he has.

He also likes that his initial gift of 50 photos didn’t end up being his entire submission. “It was hard to determine 40-some years later what was important, and what wasn’t,” he says. “It’s best to let historians of the future editorialize and decide what was most significant.”