Magazine

The Man in the Middle of the American Century

Michigan Senator Arthur Vandenberg moves from footnote to spotlight in a new, first-of-its-kind biography by Hank Meijer

by Leslie Stainton

This past summer, Hank Meijer stopped by the Bentley Library for a visit. It was a homecoming, of sorts.

Between 1990 and 1994, Meijer guesses he came to the Bentley as many as a hundred times—possibly 200—to research his biography of U.S. Senator Arthur Vandenberg, out this fall from the University of Chicago Press and titled Arthur Vandenberg: The Man in the Middle of the American Century.

So the visit in June was something of a valedictory lap coupled with a trip down memory lane. But there was also business to do. Meijer, 65, is casting about for a topic for his next book, and he wanted to pick a few brains.

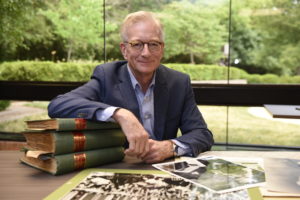

Hank Meijer at the Bentley Historical Library alongside items from the Vandenberg collection.

For a man who’s used to seeing his name emblazoned on bright red grocery trucks throughout the Midwest, Meijer, the executive chair of Meijer Inc., is decidedly humble when it comes to talking about himself. But ask him about Arthur Vandenberg, U.S. Senator from Michigan from 1928 to 1951, and Meijer can’t stop telling stories. He’s been interested in Vandenberg ever since he was a kid growing up in Grand Rapids, their shared hometown, and he first learned about “this local boy who had risen to great prominence but was now largely

forgotten.”

The Republican Vandenberg is best known for his dramatic shift from isolationist to internationalist in the aftermath of World War II — and his fierce leadership in the bipartisan postwar push to create the Marshall Plan, the United Nations, and NATO. Edward R. Murrow called Vandenberg “the central pivot of the entire era.”

Meijer had long been curious= about the senator — with whom he shares not only a hometown but also a name (Vandenberg is Arthur Hendrick Vandenberg, while Meijer is Hendrik Meijer, nicknamed Hank). It wasn’t until 1989, though, that Meijer got serious about the man he likes to call “Van.” That year, the Michigan Historical Society was seeking a speaker for its annual convention, and a colleague, knowing of Meijer’s interest in Vandenberg, asked if he’d be willing to say a few words on the “Big Michigander,” as Time magazine once called the state’s senior senator. Meijer accepted.

Two months after giving the talk, he got a phone call. It was the daughter of C. David Tompkins, a Chicago historian who’d published the first of a projected two-volume life of Vandenberg in 1970 but died before he could write the second volume. His daughter was wondering if Meijer would like to have her father’s notes. Meijer felt a tug, and the following month had a vanload of Tompkins’s files shipped to his Grand Rapids office. When the notes arrived, Meijer recalls, “I was suddenly imbued with a sense of purpose.”

Like Vandenberg, a past editor and publisher of the Grand Rapids Herald, Meijer is a former editor who worked for a weekly newspaper in Plymouth, Michigan, after graduating from U-M in 1973 with an English degree. He briefly pursued graduate work in history at Western Michigan University before returning to Grand Rapids to help run the grocery business his grandfather had founded in 1934. In 1984, Hank published a biography of his grandfather, Thrifty Years: The Life of Hendrik Meijer. Now he was embarking on a bigger book, about a public figure—a man Meijer says “is arguably the most important political figure of the 20th century about whom no biography existed.”

Meijer made his first visit to the Bentley in the spring of 1990. The library has eight linear feet of Vandenberg papers, including correspondence, diaries, and scrapbooks. Although the collection was smaller than he’d expected — “you’re aware of a dearth” — it also seemed “manageable,” and Meijer plunged in. “And once you do that,” he grins, “you’re hooked.”

Over the next three years, he drove to Ann Arbor every other week to spend a full day at the Bentley. As he worked through the files, he experienced “wonderful, magical moments” that took him “deeper and deeper” into his subject. Of special note were Vandenberg’s

drawings — he was a compulsive and gifted doodler, often sketching in the midst of Senate debates — and the scrapbooks the senator and his wife, Hazel, had painstakingly assembled, working side by side on the sofa in their Washington apartment.

At the same time, Meijer began writing the biography. “I’m part of that school where you start writing in tandem with your research,” he explains. By 1993, he had a “messy giant manuscript” more than 900 pages long — with more research to do. In addition to the Vandenberg papers, the Bentley held lucrative complementary collections, among them Hazel Vandenberg’s diaries and the papers of Michigan Republican Frank Knox. There were also records of the Grand Rapids Herald, holdings in the Library of Congress, and interviews to conduct with people like former President Gerald Ford, author Gore Vidal (who crossed paths with Vandenberg when he was a child in Washington), and Vandenberg’s daughter Betsy, whose stories and insights drew Meijer into the Vandenberg family story.

Throughout his years of work on Vandenberg, Meijer was repeatedly struck by the relevance of the senator’s story to contemporary American politics. (In her endorsement of Meijer’s book, journalist Cokie Roberts writes, “Every member of Congress should read this book for a lesson in leadership.”) A firm believer in bipartisan cooperation and an artful compromiser, Vandenberg was “a man who is willing to admit he’s changed his mind about things,” Meijer says. “He was the bridge between the isolationists who said we should mind our own business — we should ‘build a wall, America first’ — and the internationalists who said, ‘No, we can’t do that, we need the structures of things like the UN — and for that matter NATO — for our own interests.’”

Once a fierce opponent of Franklin Roosevelt and the New Deal, Vandenberg later worked closely with Democratic administrations to combat Soviet expansion and forge peace in the post-war era. In multiple ways, as the subtitle of Meijer’s book suggests, Vandenberg is “the man in the middle of the American Century.”

If his biography achieves anything, Meijer hopes it will “add to the recognition that we need people like Vandenberg today, who are willing to step out of the comfort zone of their party to try to figure out how to get things done in the country.” He hopes, too, the book will become part of the body of scholarship of mid-century American politics and policy, so that Vandenberg is no longer regarded as a “footnote” to the era, but as a vital player.

Meijer will be reading from his biography at the Gerald Ford Library at U-M on November 15. Meanwhile, he’s actively looking for his next topic. He’d like it to be connected to Michigan. With luck, it’ll bring him back to the Bentley for another hundred or so visits.