Magazine

The Mystery of the Unidentified Painting

The questions surrounding a Bentley painting from the Philippines reveal the truth about problematic and harmful content in the archive. The Bentley is part of a new effort to examine Philippine materials across campus and take the necessary steps to repair damage to Filipino communities and people. The story of a small painting is really a story about archives writ large, and who has had the power to create collections for centuries.

By Lara Zielin and Sarah Derouin

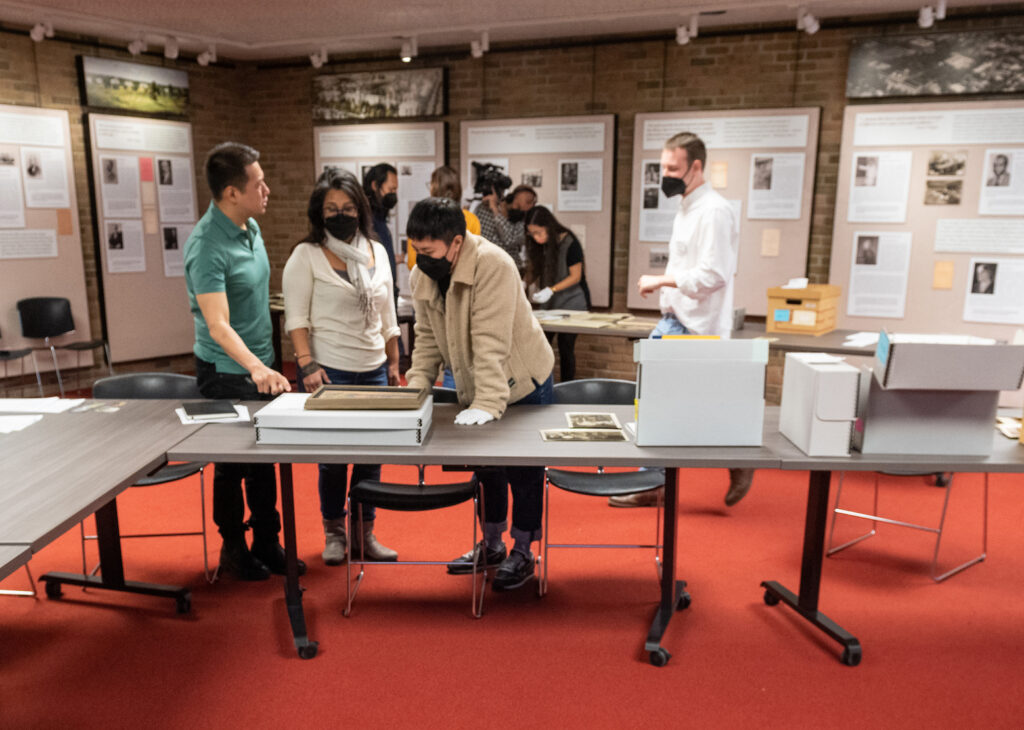

The painting lay flat on the table, a small rectangle of canvas with a dull brown frame, surrounded by archival boxes and materials.

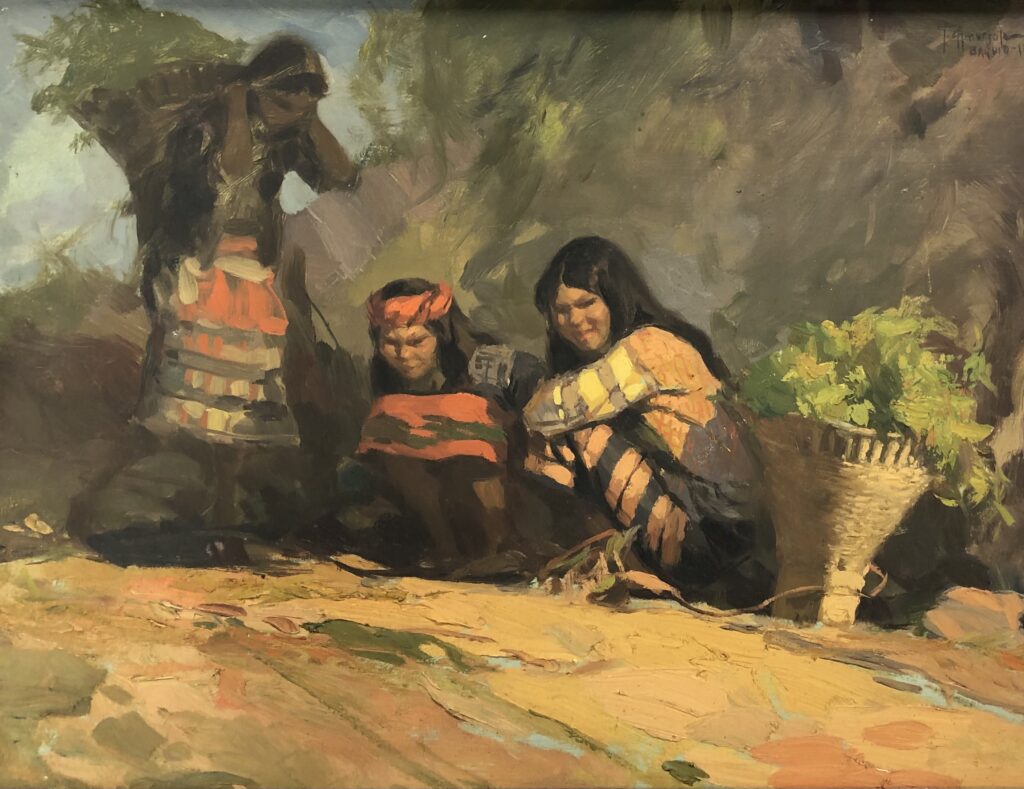

One by one, the Filipino artists and the archival team working alongside them in the library found themselves examining the artwork. They studied it. Held it up. Took in the painting’s three women dressed in bright reds, oranges, and yellows. Two of the women are depicted squatting against a small embankment, a basket of harvested greens nearby, staring out of the frame with a mix of puzzlement and possibly annoyance.

They conferred among themselves: Could it really be?

The painting had all the hallmarks of Fernando Amorsolo—a prolific painter who created an estimated 10,000 works over his lifetime, many depicting Filipino people, landscapes, and culture. An essay for the National Commission for Culture and the Arts called Amorsolo “a master of the Philippine landscape.” More colloquially, he is called the Philippine Norman Rockwell.

If the painting was an Amorsolo, it would be significant. Museum-worthy, perhaps, and an important work by the artist, likely early in his career, that would warrant notice.

Yet, in the catalog record, the painting’s artist is listed as “T. Amurgot (?)” The question mark suggests the signature was unrecognizable to the catalog creator.

It took Filipino artists visiting the Bentley in person to flag the name—and to note the painting’s potential significance.

Now, an investigation is underway to determine if the painting really is an Amorsolo. However, the question of authenticity is almost secondary to why the Bentley came to have a Philippine painting to begin with (Amorsolo or not)—or a plethora of Philippine collections, many of which contain harmful and racist material.

To understand that—and why the Filipino artists were at the Bentley that day studying Philippine-centric collections in the first place—history has to be unfurled back to the 1870s, when a U-M alum and naturalist named Joseph Beal Steere decided to go abroad to collect specimens.

Artists and faculty examine materials from the Bentley’s Philippine collections including an unidentified painting that may have been painted by Fernando Amorsolo.

U.S. Imperialism and U-M Collections

Steere was ready to collect artifacts from the other side of the world, but it was an expensive undertaking and he needed help.

His uncle, wealthy businessman, newspaper publisher, and U-M alum Rice Aner Beal, agreed to finance an expedition in exchange for letters chronicling the tour that Beal could publish in his paper, the Ann Arbor Courier.

With his funding secure, Steere mapped out an ambitious itinerary. Between 1870 and 1875, he traveled to South America, the Philippines, Taiwan, and China, with stops along the way. Steere’s collections grew, and by the time he returned to U-M, he had amassed some 60,000 specimens of plants, animals, and insects, and more than 800 cultural objects. The haul became the foundation of the first U-M museum building project and landed Steere a position as a zoology professor at the University.

By the turn of the century, the Philippines was in political turmoil. The country had been a colony of Spain before it became a U.S. territory in the aftermath of the Spanish-American War. As part of the 1898 Treaty of Paris, Spain sold the Philippines, Cuba, the Mariana Islands, and Puerto Rico to the United States for $20 million.

The Philippines wouldn’t be fully independent of the United States until 1946.

In the meantime, enter American imperialists and colonizers— and deep Michigan ties.

Some came to the Philippines as government appointees, such as Dean Conant Worcester, a one-time student of Steere at U-M. Worcester was appointed Secretary of the Interior of the Philippine Islands by President McKinley and was also an avid photographer. He documented Indigenous communities and Filipinos, and his photographic collection and archive are spread across the U-M Museum of Anthropological Archaeology, the Bentley, and the University Library’s Special Collections Research Center.

Others came as missionaries and doctors—or both, as in the case of Grace and James Miller. Grace was a teacher at the Brent School in the Philippines during the 1920s, and her brother, Dr. James M. Miller, was a U.S. Army physician at the Sternburg General Hospital in Manila during the same period.

Their collection includes letters, diaries, photographs of hospital staff, as well as images of Filipino people and scenery.

It also includes the mysterious “T. Amurgot” painting.

It’s not clear from the catalog record or donor file where or how the painting came to the Millers. It was donated to the Bentley, along with the rest of the Millers’ papers, in 2008 by Grace’s niece, Jane Miller, who died in 2013.

But what is clear is that U-M has thousands of artifacts from the Philippines spread throughout multiple campus locations—one of the largest collections of historical Filipino artifacts outside of the archipelago nation.

“A community from the Philippines has never said, ‘Here, take our materials,’” says Nancy Bartlett, associate director of the Bentley.

“It’s outrageous when you think about it,” says Deirdre de la Cruz, associate professor of history in U-M’s College of Literature, Science, and Art.

“What are these Philippine artifacts and photographs and archival materials doing here, halfway around the world, in the middle of the United States? Do Filipinos even know they exist? There’s not enough recognition of how complicit [U-M] was in American imperialism, and not enough knowledge and education about that history.”

ReConnect/ReCollect

Ricky Punzalan, associate professor of information and a Filipino scholar, wanted to upend the curation confusion and repair the damaging colonial history of the Philippine collections. He teamed up with de la Cruz, and together they are co-leading the project ReConnect/ReCollect: Reparative Connections to Philippine Collections at the University of Michigan.

The goal of the ReConnect/ReCollect project is to look at the collections with fresh eyes, repair harmful historical descriptions, and construct new models for how to best engage community members and scholars with the plethora of Filipino history stored at U-M. Punzalan and de la Cruz assembled a team of faculty, students, librarians, archivists, and community members to take on this critical reparation work.

The project also works in partnership with collections faculty and managers beyond the Bentley, including U-M Library’s Special Collections Research Center and the Museum of Anthropological Archaeology. Together, they are creating recommendations for representing Philippine collections held by various campus units.

Ricky Punzalan (left) and Deirdre de la Cruz (right) are co-leads on the ReConnect/ReCollect project.

U-M recognized the importance of this reparative work on the Philippines collection and awarded the project a $500,000 grant toward the pilot program.

“This project is really a first in terms of bringing together curators, librarians, and archivists from across campus to look at collections that are highly distributed,” says Bartlett. “We are having conversations as a team about these important collections that we’ve never had before.”

The imperialist origins of the Philippine collections are only one part of its problematic history. The collection is spread out around the campus, housed in various libraries and museums.

Artifacts are separated by campus geography, and also further isolated by spotty, poorly named, and disconnected records—as the “T. Amurgot” painting exemplifies.

“There is, at best, inaccurate information around the description of the collection, and that’s to put it mildly,” says Punzalan. “Some items have information that is just wrong, racist, or harmful to Indigenous source communities.”

Repairing the Philippine collections at U-M is crucial not only to the academic community but also to the Filipino community in Michigan and beyond.

“These are hugely important collections at an international level, in terms of the history of imperialism in the Philippines,” Bartlett says. “The University of Michigan is a ‘go-to’ destination for that highly complicated story.”

Artists in Residence

As part of ReConnect/ReCollect, three visual artists were chosen for a paid, two-week residency to engage U-M’s Philippine collections, exploring themes of archives, material history, decolonization, Filipino identity, and more.

Francis Estrada, Janna Añonuevo Langholz, and Maia Cruz Palileo were the artists chosen out of numerous applicants, and they were all present that day when the possible Amorsolo painting was identified. In fact, it was because of Palileo, a visual artist, that the painting was among the materials to be explored in the first place. They had requested it from the catalog as part of what they wished to explore at the Bentley during their residency.

“Francis [Estrada] came over and he said, ‘that looks like an Amorsolo,’” explains Cruz Palileo. “He asked if there was a signature and we googled it. It was a match, though of course it could still be a copy. Even so, there was a lot of buzz in the room when it happened. If it’s real, that’s quite a find.”

However, the painting was still part of materials that were challenging for Cruz Palileo and the other artists to view and explore: pictures of Indigenous community members being posed and exploited; sacred ceremonies without context or attribution; letters and diaries labeling Filipinos as savage and uncultured.

“It’s difficult to be entrenched in these materials, to look at history through the lens of colonization and violence,” says Cruz Palileo. “We [the artists] felt like we were collectively grieving. There was grief and anger—and some moments of joy. It was very emotional and draining.”

Those emotions, Cruz Palileo says, are being poured into the paintings they are in the process of creating now. “I’m working it out in the studio. It’s being channeled.”

All while the other painting—the possible Amorsolo—is being carefully examined for more clues that could help determine its authenticity.

Documents from the Archives of American Art at the Smithsonian Institution may be able to place the Millers and Amorsolo at a 1925 exhibit in New York, confirming their connection. Deeper research into the Miller family may uncover a letter or a photo that could provide context clues. And Punzalan hopes to share high-resolution scans of the painting with curators and conservators in the Philippines, who can help determine next steps.

“Whether or not the painting is an Amorsolo, it still speaks to many things that need addressing,” Punzalan says. “Why we had it, why it was mislabeled, why no one knew about it.

“In the archives, we do research and description, but it doesn’t mean we understand the whole story,” he adds. “This painting shows the value of connecting with the community, because so often there is knowledge embedded in the culture. The true value of archival objects comes from interaction.”

Portions of this story were used with permission from the School of Information and its coverage of the ReConnect/ReCollect project in May 2022.