Magazine

The Red Scare Comes to U-M

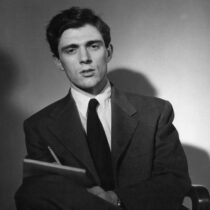

A student’s senior film project revisited the long-buried history of McCarthyism at U-M. More than 70 years later, the brave fight for academic freedom lives on through the legacy of Mathematics Professor Chandler Davis.

By Sarah Derouin

In a Michigan courtroom in 1954, Representative Kit Clardy was indignant. As the head of a House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) hearing, a frustrated Clardy had just asked U-M Mathematics Professor Chandler Davis if he was acquainted with Harlan Hatcher, the President of the University of Michigan. Despite the pair having obviously met many times, Davis refused to answer.

Indeed, for 26 questions, Davis was mute to HUAC’s questions, invoking the First Amendment, which protects Americans’ freedom of speech and assembly. Many others who came before HUAC in the 1950s pled the Fifth Amendment, an approach used to protect against self-incrimination.

Davis, however, took a principled political stand—he maintained that a person’s political beliefs were not criminal and that the actions of HUAC were wrong.

Davis’s hearing took place in the midst of the “Red Scare,” a time when fears about the spread of Communism were stoked by U.S. government officials and society at large. U.S. Senator Joseph McCarthy led the investigations into suspected citizens, and hysteria reigned. As McCarthyism spread, Americans’ freedoms were jeopardized, stoked by hearsay and intimidation. Many federal employees, known leftists, and even those in the film industry stood in front of HUAC, under suspicion of being a “Red.”

Academics were not immune in the hunt, and Davis found himself in the crosshairs.

Davis didn’t name names. He refused to say if he was or had ever been a member of the Communist Party. He would not confirm or deny authorship of an anti-HUAC pamphlet that was distributed on campus—the very accusation that caught the committee’s attention in the first place.

It was a calculated risk, and it backfired. For his refusal to answer HUAC’s questions, Davis was the first person in Michigan to be cited for contempt of Congress. He was sent to jail for six months.

Professionally, Davis also felt the consequences of standing for academic freedom. His actions were decidedly rebuffed by U-M leadership. Instead of defending the young researcher for his principles, U-M fired him, leaving the promising and well-liked academic without a professional home.

Although the experience was life-changing for Davis, U-M buried this shameful period and quietly moved on. More than three decades later, Adam Kulakow, a senior student filmmaker, heard of the Red Scare at U-M and followed the story.

His research in the Bentley Library archives and interviews with Davis and other faculty brought that fearsome time in history back into the light. Kulakow’s 1989 documentary, Keeping in Mind: The McCarthy Era at the University of Michigan, revealed the trials and fallout of McCarthyism at U-M in the ’50s. His film resurfaced a troubling time in U-M’s history, showcasing how academic freedom could be lost and buried. Decades later, the fight against tyranny and persecution is a topic that continues to resonate.

The Fight for Freedom

Chandler Davis came from a long line of leftists and agitators. Born in New York, his parents were well-educated, social justice activists, and members of the Communist Party (CPUSA). His father, Horace Davis, was a descendant of Boston abolitionists and feminists. During his life, Horace was an economics professor, steelworker, and journalist who had his own run-ins with HUAC. Chandler, who was called a “red diaper baby,” came by his political beliefs naturally.

As a young adult, Davis joined the CPUSA, but soon withdrew in order to participate in Navy officer’s training during WWII. After the war, he obtained his undergraduate and doctorate degrees from Harvard and rejoined the CPUSA. While in school, he met and married his wife, Natalie Zemon Davis.

In 1950, Davis was on the job market and almost took a faculty position at UCLA. However, the establishment of the California Loyalty Oath, which required faculty members to sign a pledge that they were not members of the Communist Party, was a deal-breaker. Instead, Davis and Zemon headed to Ann Arbor, where he became a mathematics professor and she continued her graduate studies.

The Davises’ political beliefs and affiliations continued through the early days at U-M, even as the government increased its pressure to uncover any suspected Communists. In 1952, Zemon and her friend and U-M colleague Elizabeth Douvan wrote a pamphlet called “Operation Mind.” The political publication broke down the HUAC attacks and called for protests on U-M’s campus.

Although the authors of the pamphlet remained anonymous, the FBI tracked down the print shop where it was duplicated. It so happened that Davis was the one who had signed the invoice for the prints. A subpoena soon followed.

Davis was one of three U-M professors who fell victim to the Red Hysteria and the juggernaut power of HUAC. In the end, tenured pharmacology professor Mark Nickerson and tenure-track biologist Clement Markert also faced HUAC trials.

Hatcher’s Navigation

While seeing three U-M professors on trial was a shock to many, then-President Hatcher knew it could have been much worse. In the Keeping in Mind documentary, both Hatcher and Vice President Marvin Niehuss said there were 15–20 faculty members who were originally on HUAC’s suspect list.

“The McCarthy hysteria and the extremes to which they were going had become entirely apparent,” said Hatcher. “They were very destructive and the question was how to preserve the integrity of our institutions in the face of that threat.”

Hatcher called the FBI’s list unjust and outrageous, but he felt that he had no choice but to face the issue head-on. He asked Niehuss to travel to Washington to argue for the accused and to whittle down the names. In Hatcher’s words, “as a result of our efforts, we were able to clear . . . and remove from any public display all but three members of our faculty.”

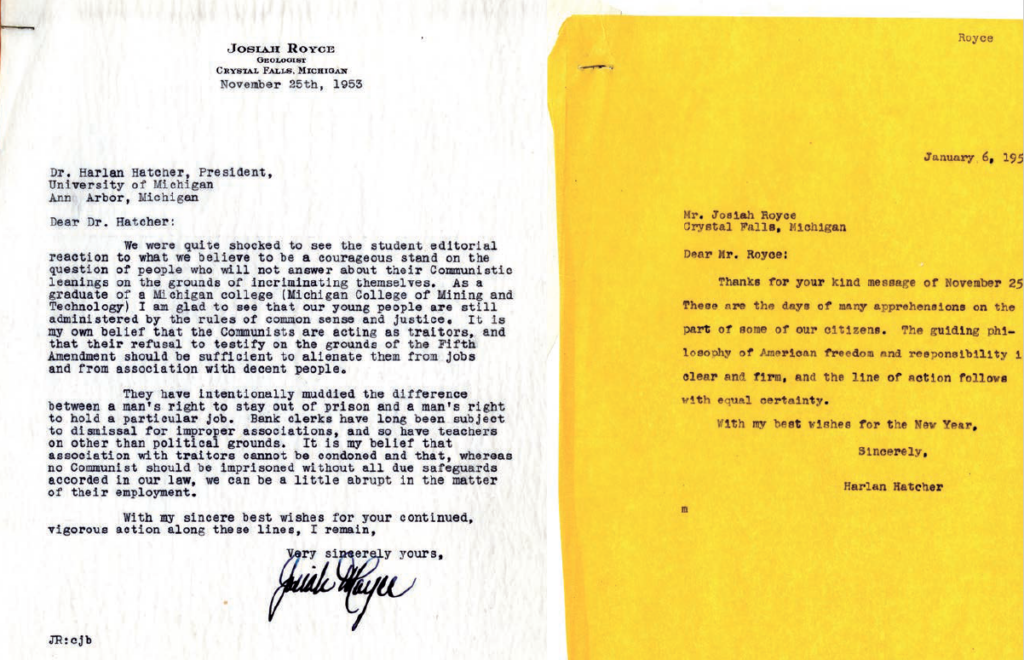

Kulakow said the public frenzy and government pressure were instrumental in how Hatcher had to navigate the HUAC faculty hearings. Hatcher received many letters from alumni across the nation, condemning the political protests by students on campus, and praising the efforts to put “Commies” in their place. His responses to these letters, which can be seen at the Bentley, are measured and often contained a comment about living through a troubled time.

On the left, an archived letter shows support for President Hatcher; on the right, a a confident reply indicates Hatcher may have felt he alleviated a bigger crisis by suspending three faculty instead of the 15–20 faculty on the FBI’s initial list.

Kulakow said he wanted to have Hatcher’s voice in the film and he was somewhat surprised when Hatcher agreed. “I felt like it was important for him to talk about the pressures that a university was under at the time,” he said, adding that Hatcher frequently referenced the period as a “unique time and place.”

“I don’t think he understood Chandler Davis—I think there was a big generation gap there,” said Kulakow, adding that a young, opinionated, and principled person like Davis put Hatcher in a tough position. “He came from an institutional loyalty point of view. And in his world, I think that was the biggest consideration.”

In the film, Davis said he was frustrated with his inability to get through to Hatcher about the position he was taking with the investigations. “He tried hard to make his case and really got nowhere with him,” Kulakow said.

A Brave Defense

The most common defense for those facing HUAC was to plead the Fifth Amendment, citing the right to not self-incriminate.

Taking the First Amendment was a risky approach, said Nickerson in Keeping the Mind. He said that with three children, he couldn’t take the chance that Davis took. For him, taking the Fifth “gave me more leverage with the University committee . . . it was the one that was safe as far as being able to support my family.” In the end, Nickerson invoked both the First Amendment and the Fifth in his Clardy hearings.

Markert also took the Fifth, refusing to answer questions. “I didn’t want to talk about anything substantive before the Clardy committee because, in my view, the government is mine, it represents me. It has no right to ask me anything about my political opinions or activities.”

In contrast, Davis cited the First Amendment during the Clardy hearings. Ironically, he hoped his approach would lead to an indictment, as he planned to challenge the constitutionality of McCarthyism. “The motivation was my resolution to face the Red Hunt as squarely as possible,” wrote Davis in “The Purge,” an essay included in the 1988 book A Century of Mathematics in America (American Mathematical Society).

The HUAC hearings were used to identify suspected Communists in the U.S., but personal punishments were handled by the employers. Most of the accused were fired and carried a black mark, hurting their chances for new jobs. After the Clardy hearings, Davis, Markert, and Nickerson faced U-M faculty committees to decide if they would keep their positions.

While Markert and Nickerson fully cooperated with the faculty committees, answering their colleagues’ questions, Davis refused. He saw the academic committee as a continuation of HUAC and believed they were “not interested in thoughts on free speech.” Davis faced three university committee hearings, two of which recommended dismissal.

After the three U-M faculty members invoked their constitutional right not to answer questions in front of the House Un-American Activities Committee, U-M President Harlan Hatcher suspended them, making front-page news in The Michigan Daily.

Davis and Nickerson were both fired, while Markert’s job was spared after a suspension. In the documentary, Hatcher said Markert was the only one who spoke “properly” during the faculty questioning. “It was such a contrast . . . between Mr. Markert and these other two who were defiant and not forthcoming and not honest and forthright.”

Davis’s brave plan to argue against the plague of McCarthyism was not to be. The U.S. Supreme Court refused (in a vote of 6–2) to hear his case. Davis ended up serving six months in prison.

Davis and Nickerson both struggled to get jobs after their firing. After leaving prison, Davis’s recommendation letters used covert wording to hint that he was tied to Communism, for example that he was “concerned with social problems.” This naturally slowed his job hunt. He eventually found a position at the University of Toronto, where he spent his tenure. Nickerson also ended up in Canada, working at McGill University. Both considered themselves political refugees.

Revisiting Old Wounds

For decades, U-M’s run-in with McCarthyism was buried and almost forgotten. But in the late 1980s, a celebration of the Rackham Graduate School opened old wounds.

“Part of the celebration of the Rackham anniversary was a symposium in which David Hollinger, then on the history faculty at U-M, gave a paper titled ‘Academic Culture at Michigan, 1938–1988,’” said Gary Krenz, director of the Judy & Stanley Frankel Detroit Observatory. “This became a very influential paper here at U-M, and I believe his discussion of Davis, Markert, and Nickerson in that paper was the first time in many years that the matter of their mistreatment had been raised here.”

Around the same time Hollinger’s paper was getting some attention, an article in The Michigan Daily was published, arguing for a name change for the Hatcher Library. Kulakow said the article caught his eye, especially hearing about Hatcher’s activities during the McCarthy Era. As an honors English major at U-M, Kulakow was required to do a senior project. Curiosity piqued, he decided to make his documentary about U-M and the Red Scare.

He immersed himself in historical records at the Bentley Library, sifting through subpoenas, University resolutions, correspondence with University officials, and old Michigan Daily publications.

“David Hollinger was very supportive of this project early on, and he had some relationships with people who knew Davis, Markert, and Nickerson and people who were there involved in the history,” Kulakow said.

In addition, Kulakow got phone numbers for the three men and started making calls. To his surprise, “each of them was totally open to talking to me—it wasn’t even difficult.” Kulakow and his small film crew interviewed Davis, Markert, and Nickerson at their homes, spending hours with the men and their families. “Each of them was incredibly gracious, they were life-changing people.”

The documentary screening was held in Ann Arbor in April 1989, and Davis, Markert, and Nickerson all attended the event. “That was the first time the three of them had all come back together since the ’50s,” Kulakow recalled.

It was a packed house. “The crowd was raucous. There was a moment in the film when Clement Markert was talking about his time with the Abraham Lincoln Brigade [his military service during the Spanish Civil War] and he said, ‘Well, you know, naming names—I would never do that. They could have put me up against the wall and shot me,’ and the crowd absolutely went crazy,” said Kulakow.

“I don’t think, as young people, we’d ever heard someone speak with such deep conviction, who had laid so much on the line for free speech and for decency. That was incredible and it was full of those moments,” he said.

Apologies and Non-Apologies

After the April 1989 showing of Kulakow’s documentary, there was an outcry for justice and making amends. The U-M chapter of the American Association of University Professors (AAUP) sprang into action, contacting University officials to encourage the University of Michigan Regents to make amends to Davis, Markert, and Nickerson.

AAUP sent a proposal to the Senate Advisory Committee on University Affairs (SACUA) in October 1989. In turn, SACUA petitioned the Regents to issue an apology and take some tangible action. The request was ignored. As a result of the failure to make amends, the Senate Assembly passed a resolution that recognized “the failure of the University community to protect the values of intellectual freedom.” They also established the Davis, Markert, Nickerson (DMN) Lecture on Academic and Intellectual Freedom to celebrate the brave actions of the three faculty, and the Academic Freedom Lecture Fund (AFLF).

“AFLF and SACUA on more than one occasion over the years endeavored to elicit a formal apology by the University, but nothing ever came of it,” said Krenz. “But in 2005, the Regents approved the Davis, Markert, Nickerson Visiting Professorship in Academic and Intellectual Freedom, submitted by the provost and dean of Rackham. Was that effectively an apology? I don’t really think anyone saw it as such at the time.” To date, no one has ever been appointed to the professorship.

The first Academic and Intellectual Freedom lecture was in February 1991; all three professors attended and participated in a panel discussion afterward. Today, the DMN Lecture still features an annual speaker, and lectures are open to the public.

Lessons of Yesterday Resonate Today

The interviews, followed by the intensive process of filmmaking, made a deep impression on Kulakow that lingered for decades. “I started to talk like them, I heard their voices so much,” he said. “I still feel very close to them.”

He stayed in contact with the three men throughout the years, emailing frequently and seeing them at the DMN lectures. After graduating from U-M, Kulakow taught film, literature, and writing at Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts, then went on to UCLA Film School—two opportunities that he says resulted from making the U-M documentary. Kulakow is still making documentary films, screenwriting, and producing, working on projects all over the world.

The gravity of their experiences lingers and is as powerful as it was when he first made the film in 1989. “I remember speaking with Davis at the 25th anniversary of the lecture,” recalled Kulakow. “I got very emotional because I can’t believe that the University hasn’t honorarily reinstated them. I cannot believe it. Especially given that we celebrate what they did today. I remember saying to the audience at the lecture, ‘Why isn’t there a statute to these three?’”

All three men are now deceased: Nickerson died March 12, 1998, followed by Markert on October 1, 1999. Chandler Davis died on September 24, 2022.

Kulakow wanted to make sure their story, their experience, was never lost. All the interviews (including those that didn’t make it into the film), documents, and film notes are archived at the Bentley Historical Library. “The Bentley was important to the project,” Kulakow said. “They were wonderful, just so supportive. It was such a thrill to give [materials] back to them and be a part of the archives.”

[Lead image: Chandler Davis photographed circa 1952, U-M News and Information Services]